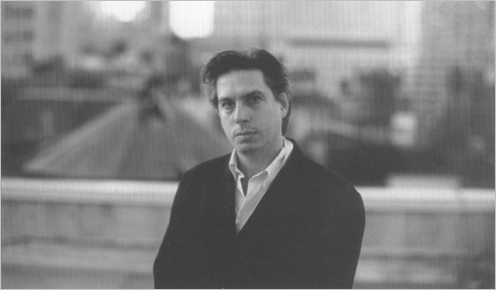

High atop a dark gothic-looking apartment building in the middle of downtown Manhattan lies Zarathustra Music, the office and studio of Elliot Goldenthal.

On Wednesday, July 14th, at approximately 2:00 a.m. in the morning, I arrived at this location to ask Elliot why he calls his domain Zarathustra Music. He responded:

“Frederick Nietzsche, who’s a great philosopher of Polish descent in the German world, was primarily interested in the music of Richard Wagner and extremely taken up by his work. He wrote a book called The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music, which tried to relate the early Greek concept of theater – combining acting, music, and dance all together – to the work of Richard Wagner, the great racist German composer. It turns out that Nietzsche, who was very critical of all religion in his philosophy, was upset that Richard Wagner chose only Judaism to be the religion that he picked on. Wagner wrote a book called Jewishness in Music which said that it’s impossible for Jews to be composers because they had no sense of nationalism. In another book he wrote, ‘The only thing we can hope for is a Jewish-free Europe.’

“Nietzsche though of Wagner as a whore, because if he promoted anti-Semitism he’d be more popular. He thought that however Wagner could get popular, he’d do it. Nietzsche left and broke off with him in the later years of their relationship. He was very upset that Wagner had become not only a racist, but the kind of racist that built the infrastructure of Hitlerean thought. Hitler actually started taking up on this idea, to the extent of when he was incarcerated in the 1920s in jail and was writing Mein Kampf, he had no stationary, so he sent for Winifred Wagner to send him some stationary from the Wagner estate to write Mein Kampf on; there’s a tremendous connection there.

“For many years Nietzsche was considered to have been associated with the Nazis. He was one of the least racist characters in Europe; it was disgusting to him. Nietzsche the philosopher had also written Also Sprach Zarathusta or Thus Spoke Zarathustra, which has a philosophical treatise or story to tell. After he died his works were twisted around by Hitler, his sister, as well as his brother-in-law, and he was thought of as being some sort of Nazi racist character when it was just the opposite. It’s like turning Martin Luther King into a racist.

“I named my company Zarathustra Music so people can ask me those questions and I can talk to them about Nietzsche and Wagner. I adore the music of Wagner and the writing of Nietzsche, but I think people have to be very careful to subdivide the music, teachings, and philosophy of Wagner. I love his music, but he was an evil man.”

After being mesmerized by this intellectuality, I sat down to watch an exclusive promotional video of his latest film scoring project, “Titus”. “Titus”, directed and nurtured to the big screen by director, artistic partner, and his wife, Julie Taymor, is a timeless powerhouse of intense drama with visual elements on a grand scale defining the meaning of the word ‘epic’. It looks, sounds, and feels like classic cinema, but with a daring new original approach which is highlighted by a Goldenthal score that combines all of his evocative styles into one sonic vision.

Many of Goldenthal’s projects are as challenging as the scores he offers them. He always takes an untraditional approach to tell the film’s story, unifying all the dramatic and emotional elements, and seriously supporting the film as a whole in his wildly original and unpredictable fashion. His film projects have dealt with a vast array of subjects, reaching from one end of the spectrum to the other. Whether it’s his experimental musical journeys into dark psychological worlds such as “The Butcher Boy”, “Drugstore Cowboy”, and “In Dreams”, his other-worldly adventures in “Alien 3” and “Sphere”, those flamboyant mythical comic book operas “Batman Forever” and “Batman and Robin”, to his overtures of horror in “Interview with the Vampire” and “Pet Sematary”, and those intense epic dramas like “Michael Collins”, “A Time To Kill”, and “Cobb”, Goldenthal offers all his directors a musical passageway to the great unknown. In his film scoring journeys he has received two Oscar and Golden Globe nominations for his scores to “Interview with the Vampire” and “Michael Collins”, Grammy nominations for “A Time To Kill” and “Batman Forever”, three nominations for the Chicago Film Critics Award for “Heat”, “Michael Collins”, and “The Butcher Boy”, as well as winning the L.A. Film Critics Award for Best Original Score to “The Butcher Boy”. Goldenthal has also won an Obie Award with his wife and director Julie Taymor for their collaboration on Juan Darien: A Carnival Mass. Beyond all of these awards and nominations he continues to compose for film, theatre, symphony, opera, ballet, and quartet, at a frightening pace. Elliot Goldenthal is the musicians’ musician and a true composer in every sense of the word.

Flash backwards twelve hours, Tuesday, July 13th at 3:00 p.m., when I met Elliot for the very first time at his Manhattan offices. We sat down for the first five hours of an eight-hour interview covering his views on making film music, all of his scores, the directors he’s worked with, composing outside of the film medium, and a unique discussion on his new film score to “Titus”. This all brings to mind a line from “Titus”, as actor Anthony Hopkins gracefully says to the viewing audience: “Welcome All.”

CONTENTS

Act II: Techniques in Film Scoring

Act III: The Ten-Year Moment

After five hours of face-to-face conversation, my interview with Elliot Goldenthal continued by phone, getting more involved as our discussions developed. One interview that took place from 2:00 a.m. to 3:00 a.m., while he was at Skywalker Sound mixing down “Titus”, left Elliot and I both stunned. Afterwards I commented, “You’re welcome to call me for our final interview when you’re ready.” He responded, “The next two or three days are probably going to be intense, but I can dance between the raindrops and call you up if it doesn’t bother you. As soon as I get up I’m nuts. The birds are pecking at me in every way.” A casual reference to Hitchcock?

These interviews reveal Elliot’s attraction to scoring Shakespeare with his latest film score to “Titus”. We also take a behind-the-scenes look at his scoring team: the people who are part of the Goldenthal machine that you never hear about. His producer, orchestrator, electronic music producer, the conductors, and his engineer all give their personal views on working with Elliot. Next time in part three we explore Elliot Goldenthal the composer; a candid look at just a few ambitious projects he’s created outside of film scoring. From his oratorio “Fire Water Paper” to his ballet work “Othello” to the carnival Mass “Juan Darien”, and his ambitious opera “Grendel”, Goldenthal’s non-film work travels at a steady pace alongside his film scoring career.

Behind Elliot Goldenthal exists a compassionate man who works in a world of never-ending ideas, whether it be film, theater, opera, dance, or classical composition. This ‘musicians’ musician’ keeps creating new and clever ways to compose all kinds of music. Twenty-four hours in one day is not enough time for Elliot. He’s a workaholic powerhouse running hour after hour, getting very little sleep, making his musical visions come true in every waking moment. It’s 2:00 a.m. somewhere high atop a dark gothic-looking building in the middle of downtown Manhattan. A light glows mysteriously on the top floor; and if you listen carefully you can hear the distant sounds of music emerge as another project from Elliot Goldenthal surfaces to give the early morning new life.

The Goldenthal Scoring Team Speaks on 'Titus'

Act VI: Elliot Goldenthal's Scoring Machine

Act VII: Film Scoring Resolutions

Elliot Goldenthal’s non-film projects deal with provocative subject matter combined with stunning visuals. They offer new avenues and a challenge to conquer new musical styles or areas that the composer has never ventured into before. All of the musical styles lead back and forth to Goldenthal’s film scoring, while all his developments in style cross-fertilize each other and create an evolving maestro with a constantly-changing hybrid sound. From the music to Juan Darien and ‘Shadow Play Scherzo’ to “Drugstore Cowboy” and “Titus”, from “Interview with the Vampire” to ‘Fire Water Paper’, from “Othello” back to “Interview with the Vampire”, all his musical projects feed each other from style to style. No matter how much Elliot cross-fertilizes, each of his projects has its own individual feeling. As director Julie Taymor puts it, “Elliot makes them freshly Goldenthal.”

We now travel into uncharted lands with Goldenthal’s non-film scoring projects to reveal the complete picture of the composer incarnate.

'Fire Water Paper: A Vietnam Oratorio'