How did you meet Elliot?

I was asked to take over the “Batman” franchise and wanted to give it a totally new spin, feeling, and atmosphere, so I wanted to have our own composer. Gary LeMel suggested Elliot and sent me a tape of “Demolition Man”. I got in my car leaving home, put in the tape, I heard about five bars, and then I called Gary LeMel and said, “This guy’s a genius. When can I meet him?”

Elliot was out in L.A. and he came to my house. We talked and I enjoyed being with him very much and was very excited about working with him. We’ve done three films together and I also got to know Julie. I saw two of Julie’s productions, Juan Darien and The Green Bird. It was obvious to me that these two brilliant people were doing extraordinary work. In Elliot’s case, he was already getting recognition; in Julie’s case she was certainly getting recognition from the critics, but it’s a wonderful thing that Tom Schumacher (no relation) and the other people at Disney gave her the opportunity so that everyone could enjoy her art. I don’t mean to go off on Julie, but when you become friendly with a married couple, in your mind and emotions they are inseparable.

Elliot and I did three films together: “Batman Forever”; “Batman and Robin”; and “A Time To Kill”, which is certainly one-hundred-and-eighty degrees from the “Batman” scores, which are very exciting, full-tilt boogie, big explosive scores with a lot of humor and a great deal of tongue-in-cheek.

I think music either elevates a film or detracts. When we did the first score to “Batman Forever” we worked with the top musicians in L.A., who plays on almost every movie and are very much in demand. After we had been working for a while, on one of the breaks, some of the musicians I’ve known over the years, that are quite legendary in the Hollywood music scene, came over to me and said what a pleasure it was for them to play Elliot’s music because it’s extremely complex for movie music. A lot of film composers can take a simple theme and then just re-orchestrate it fifty times in a movie, and that’s the score. There’s nothing wrong with that if that’s what they want to do and that’s what the director wants, but Elliot’s work was extremely complex. It gave them an opportunity to be challenged more than they would on an ordinary score.

When you first heard “Demolition Man” what came to your mind?

I don’t know; music is visceral. I knew there was no one quite doing that, certainly in the Hollywood community. It was so complex and dense, yet spirited and accessible. It was definitely someone who was very classically trained, and it didn’t sound like an ordinary movie score.

How do you communicate to Elliot what type of score you want for your film?

You don’t talk that specifically, so he would play me little pieces and say, “How do you like this?” or “I was thinking of this.” Almost always I liked them. I changed very little on his scores because we were pretty much in synch. On “A Time To Kill”, because we had such a successful relationship on “Batman Forever’, I didn’t tell him much about it.

I cast the composer sometimes even before the actors, which a lot of directors who I know don’t do. They make the film, then they look for a composer. The problem with that is, I would imagine that the person you want sometimes may not be available. You’d have to get who’s available then, and that is too frightening to me. I’d handle any artist that’s working with me the same way. I wouldn’t ask an actor or actress to work on a movie and then tell them what to do. I would send them the script; if they respond to it, I would listen to why they’re responding to it and then generally add whatever I need to work with them on, because each actor or actress is different. The same with Elliot. He knew about “A Time To Kill” because I asked him to do it early on. It’s a very specific piece in many ways that is kind of Asian. I think southern courtroom racial dramas can typically be scored with a harmonica and banjos; there’s nothing wrong with that kind of sound, but Elliot took an almost Asian approach. I think this added a great deal to the score and was not an obvious choice. The score is not hopelessly sentimental.

When working with Elliot you went from “Batman Forever” to “A Time To Kill” back to “Batman and Robin”. This seems like a very difficult transition from genre to genre.

Well, I think it shows Elliot’s versatility. But in the case of “Batman and Robin” he had already established many things. In other words, there was a Batman theme, a Robin theme, an action theme, a fight theme; of course, he wrote many new things because we had new characters. There was Poison Ivy, played by Uma Thurman, so there was a lot of oriental and arabesque influences in that because she’s a seductress; it was sultry, and we never had anyone in a Batman movie like that before. Then Arnold Schwarzenegger had this big Nordic god, Mr. Freeze, so those were new themes as well.

Elliot had already established some themes though – a Bruce Wayne theme and the more sensitive themes. I think in some ways we got a short hand and in some ways some things were certainly refreshed, but they didn’t have to be invented from scratch.

What do you think led Elliot to connect up with the intense drama of “A Time To Kill”?

I think Elliot can do anything. He had already done some of Neil Jordan’s movies by then, including “Michael Collins”, which is a very intense drama. When I met him he was just finishing his Vietnam oratorio, ‘Fire Water Paper’, so Elliot can do anything. One of the most fun things was in Julie’s production of The Green Bird, which Elliot did the music for; he put some of the “Batman” score in the show, which was great. I went to see it with him; we sat together and that was so much fun.

When Elliot scored “A Time To Kill”, he mentioned that he scored the Klan’s point of view in a heroic way.

You wouldn’t tell the actors that are playing the Klan to play it like cowards. When Keifer Sutherland leads that group of people around that corner of that square of Mississippi, he’s not marching as a coward, not does he think he’s wrong. Also, the image of the Ku Klux Klan is so reactionary when you see it. It doesn’t matter what music you put there; everyone gets it. But in no way, shape, or form does it glorify them.

I hope, if I’ve done one thing in my career, I hope that I’ve created an open atmosphere so that artists like Elliot feel free to take risks. For instance, at a climactic moment in “A Time To Kill”, when Sam Jackson is set free and he walks out of the courthouse, he runs towards his daughter and they embrace. It’s a very emotional moment in the movie. At the moment of their embrace Elliot had put in a very dark ironic note. His point was very intellectual: it was that, even though Sam had won, this little girl had been raped and almost murdered and there were consequences. It was absolutely appropriate intellectually, but this is after two hours and twenty minutes of pure drama. When you rip an audience open it’s either a tragedy, and that’s the inexorable end you’re going to, or you’re healing in some way. This was a moment we needed to heal, so I asked him to take that note out. It bothered him as an artist because I understood intellectually what he was doing; but on the other hand I thought the audience had been through enough.

When Matthew McConaughey stands in front of this jury – without any music, incidentally – and tells in graphic detail for seven minutes what happened to this child, you know you need a break. You need a moment to take a breather because these people have a moment of happiness. Everyone in the audience knows that any child who is raped that many times and almost murdered is certainly going to bear scars of that, emotionally and physically, her whole life. Enough already. She can hug her father happily and have a moment of joy in the film.

Did Elliot’s film scores satisfy your vision as a filmmaker?

Oh! They far exceeded my hopes. All of his scores were really great.

What did you find unique about Elliot?

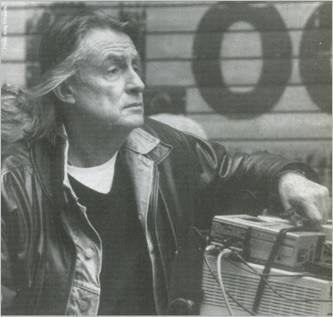

I think Elliot’s a star. I think he has a star personality. He’s theatrical; quite a colorful and interesting character. He’s almost like someone from another era, which is strange to say about someone who’s so contemporary, but he conjures up beat-up velvet jackets with hair hanging in front of his face, staying up all night. A true bohemian in a garret, struggling with his art all night long, and is wildly passionate, prone to great mood swings of great joy and depression. There’s a little bit of Oscar LeVant in him, a little bit of La Boheme in him; there’s a little bit of Toscanini in him, there’s a little bit of Pre-Raphaelites in him. So he’s a romantic character. He’s romantic and theatrical and charming.

Will you hire Elliot again to score one of your pictures?

If the movie’s right, absolutely. Of course.