At the same dark-looking gothic apartment building, in the middle of downtown Manhattan where Zarathustra Music exists, is LOH, Inc., or the offices of director/writer/producer/designer Julie Taymor. Loh is a Balinese word that means ‘the source’. As Taymor explained:

“I was in Indonesia; this was in my early twenties for four years, and I was in a culture – Balinese and Javanese culture – where there wasn’t a word for art. In Bali, there was no word for art because that’s what people do. It’s just part of your devotion as a human being.”

This all transcends back to the meaning of why her company is called Loh. Definitely not as controversial or political as the meaning to Zarathustra Music, but direct and none the less evocative.

What films has Elliot scored for you?

Just “Fool’s Fire” and “Titus”. “Fool’s Fire” was an interpretation of the Edgar Allan Poe short story ‘Hop-Frog’ for American Playhouse.

How did you discover Elliot’s film music?

We met in about 1980 through a mutual friend who was a movie producer, and Elliot had just done some films for him – “Cocaine Cowboys” and “Blank Generation”. As weird and as unsettling as those films were, the music was wonderful.

What is your greatest challenge as a director when dealing with film music?

The challenge is not to be seduced into putting music where it’s unnecessary. It’s finding the balance between scenes that work and have a power without music and figuring out exactly what the music adds. With a lot of movies, music saves the movie; that’s not out case in this movie. The movie worked very well on one level without music, but the music brings a whole other power to it. The challenge is not to step on the humor or become too cuey or to be manipulative, because sometimes the music actually can take you out of a scene as opposed to keeping you into it. The challenge is knowing exactly where to put the music, how much you need, and at what level. It’s just so that it doesn’t necessarily overpower the movie.

How do you feel about directing your first major motion picture?

Well, I’ve been working on “Titus” on and off for about four years, but totally for two years. I’m very proud of the movie and I think it’s a great film. At this point I just can’t wait for it to be done and out there because I’m very excited and want the audiences to see it; it’s an unusual film.

Elliot and I first worked on the theatrical production of Titus Andronicus; I directed it and he composed it. At that time I had a feeling that this would make a great movie, so I adapted the play into a film script, sought out producers, money, and put the whole thing together. I’m one of the producers of the film as well as directing it.

Did your directing experience in the theater help you out when doing the film?

Absolutely. I wouldn’t have even done if as a film if I hadn’t done it in the theater. You need to really discover a Shakespeare play by directing it, by doing it. I don’t think I’d have the confidence to really engage actors on the level of the actors that I have without feeling like I knew the piece inside and out. So the experience of directing on a stage gave me a familiarity, an understanding, a point of view, and a strong feeling about what I wanted to do with it, which you wouldn’t have if you just were reading it cold.

Did anything from the theatrical production bleed into the film version?

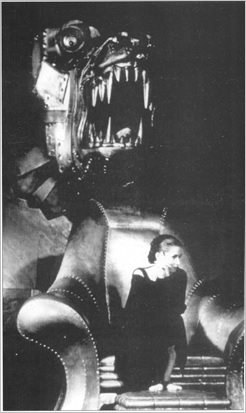

Yes, many things, but they had to be altered from something that was made for theater to something that would be cinematic, but many of my visual ideas and choreography I translated into cinematic terms. In the theater it was minimalism; we had almost no sets, it was pared down, but there was a certain kind of concept to that that still is in the film. The blending of time and the fusion of time and period was definitely something that had started in the theater. Quite a lot of Elliot’s music from the play is in the movie, treated, but the orchestral part wasn’t in the play because the play did not demand that scale. It’s the trumpet duos or the funky ‘pickled head music’, as Elliot called it. It’s the scene where the heads come back in jars; it had this sort of raw sound, or things with only two musicians. We used some tape and we used some of his film music when we did the live play. However, the grander parts of the movie had very little to do with the play.

What do find unique about Elliot as a composer?

I think he’s unbelievably versatile; he’s not a one-note Johnny by any stretch. He can really move from jazz to fully emotional full orchestral to symphonic music to world music. He’s got so many layers, not only in his background and knowledge, but in his ability to put things together and yet always make them freshly Goldenthal. They always go through his vision; he doesn’t copy. You can really tell it’s him, yet it’s tremendous diversity. He basically can do anything!

I think he can do great comedy, like when he does The Green Bird for me, the commedia dell’arte. He can do rock ’n’ roll and jazz. He’s just got all of this ability in his talent. He’s got a tremendous sense of orchestration, so he can go from very small odd pieces like “Drugstore Cowboy” or “Butcher Boy” to big, giant, blown-up cartoons like “Batman Forever” to very powerful emotional films like “Michael Collins” and “Titus”. He’s just got it all; there’s nothing that I don’t think he could do.

When working with Elliot on “Titus”, is there any one experience that stands out in your mind?

Well, I’ll tell you, where we had our most problems was with the temp score. I think that the next time we work together, if we’ve got the time, I would like Elliot to temp the movie. Because I think for all composers the temp score is terrific for the director; they’re fantastic to learn about how music works, but you get wedded to music. We temped “Titus” with a lot of Elliot’s other work, so it’s a burden on a composer to have a temp score, it’s a burden. It’s only helpful for the producers, director, and editor. Next time I’d like him to temp and try stuff out, have enough time so he can do his own temp using synthesizers and then learn from his own music. I think that Elliot’s done well to be able to not follow the temp, but in a way compromise with it. It was a big challenge because the only thing that causes tension between a director and a composer is that the director often becomes wedded to the temp score. It’s hard for them to let go and start over again. Having worked with Elliot for fifteen years on all these different projects I know how creative he is, yet that was the only obstacle, in that we had to get a temp score faster than he could temp it himself. So you have to have the luxury of time where a composer can start from scratch.

How did you communicate with Elliot on the kind of score you wanted?

First of all, we’d done it in the theater, so we already had a lot of vocabulary under our belts together about what kinds of things we needed. Then Elliot came to Italy many times and, as we were shooting, we saw how big the movie became compared to the stage, so we started to say, ‘The scale of it is larger.’ It’s a larger orchestral piece that will have its moments of funk and big band and the kind of stuff that I love from his other scores, as I said, “Drugstore Cowboy” and “Butcher Boy”. We talked about the fact that his music has to be various worlds colliding just like time, just like the period, the costumes, and the sets are. So it gave him tremendous leeway because his music corresponds to what’s on the screen visually.

Because Elliot has scored many of your theatrical projects like Juan Darien, The Green Bird, Titus Andronicus, and others, was it easy to get the score you needed from him because of his experience with you before?

No, I don’t think this was easy. I think that, for him, maybe he thought it would be even easier, but I think that what’s different from this and the theater is that I’ve been involved in the film a lot longer than he has, and I was very fussy and particular. It wasn’t as easy as he necessarily [laughter] thought it would be. There were many cues that had to be worked on and yet some of the cues just blew me away on the first time, but there was a balance between finding something that I agreed on as well, where I liked what he had done as well. It took development; it was not an easy score for him to do and once he kicked it in it was tremendous, but it took a while finding that voice. I think it’s because there were so many possibilities with it. It’s a gorgeous score, just gigantic. The opening title sequence with the march is just spectacular; it’s like ninety men singing in a chorus. It’s on the level of a Stravinsky or Verdi Requiem. It’s huge, huge, and it was thrilling to be in Abbey Road listening to that orchestra play his music.

How has Elliot’s music influenced you when directing “Titus”?

There were a couple of things I needed to be written ahead of time. There were other things that we literally did take from the play because we loved the music, so he had it played again fresh for the film, so I knew what I was going to have in certain places. I wanted to have big bang. We discussed it and he did about ten different pieces for me. I chose one and we shot what that music playing. I knew what the march was going to be in skeletal form before I shot that in the colosseum in Croatia. He did it for me because he was the first person I hired on the film. It wasn’t hard to do because we had a very good sound guy who got a DAT; he put it to tape and we played it. There’s no dialogue in those scenes, so it’s shot with a track that you follow, but then you have to re-record it later. The band in the big band part had to learn the piece so they could look like they were literally playing it.

How does Elliot’s film scoring work with your vision as a filmmaker?

It’s absolutely compatible. That’s one of the things we like so much about each other. Ultimately, even if it takes a while to get there, we have a very similar sensibility, so it fits very, very closely. I think the music Elliot has composed is absolutely great for this film.

As a director, what are your future plans?

Elliot and I are going to do The Green Bird again on Broadway this year in New York. I have a couple of film scripts that are in various stage of development. Also, Elliot and I have the opera Grendel to do. So we’ve theater, opera, and film. I don’t think that there’s a need for me to work with another composer in film; I think I’ve got the best out there. That doesn’t mean I won’t work with other composers on pieces, but, if it’s my choice, I pick the best [a little low-keyed laugh].