This was unusual. You got right back into this genre again after “A Time To Kill”.

Joel Schumacher was very nice to me. He calls me, “How’s my genius doing?” Take that with a grain of salt. He says, “You know what happens when you did the most successful film of the year? They let you do it again. So if you’ll do the movie, I’ll do the movie.”

By now did you have total creative freedom?

I had freedom, but he was there in the orchestral stage making suggestions, and there were changes. He was usually right. At one point in “Batman Forever” I did the circus scene the way I saw it. I wanted to suck out all the sound effects and to have it very delicate; you know, the part when they fall off the trapeze and he loses his family. Very religious-like. Joel didn’t like the idea; he wanted it to be high drama and suspense. In front of everybody I said, “Joel, must this be Hollywood?” It wasn’t the proper decorum or the thing to do.

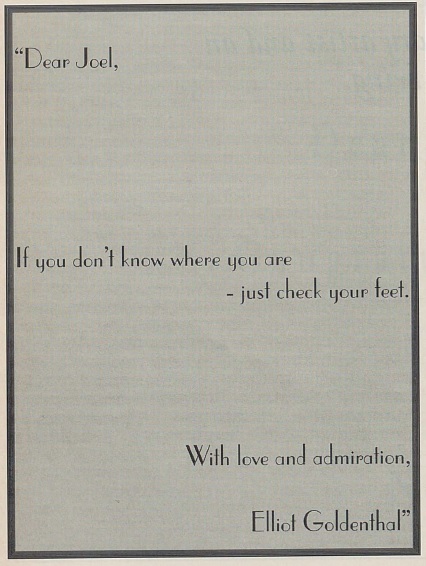

He put his arm around me. We walked out and he took me outside of the studio and said, “A friend of mine once said that if you’re ever unsure about where you are in life, just check your feet.” He pointed to the studio MGM sound stage and said, “MGM, Barbra Streisand, Judy Garland, Fred Astaire, Hollywood.” I said, “You’re right Joel; you’re absolutely right.” He said it affectionately, although he was making quite a deft and rather direct point.

This is your first sequel because you’d already scored “Batman Forever”. Did you decide to score “Batman and Robin” differently?

When you have different characters like Poison Ivy or Mr. Freeze, they needed totally different types of music. However, I wanted there to be a sense of continuity where you heard modified repetitions of the themes that you heard from the earlier movie, so you can get a nice feeling of being in the same heroic world. When I go to a James Bond movie, I want to hear that signature theme, but I also want to hear new themes and scoring each time. I think it’s enjoyable for the audience to hear the Batman march and maybe one or two other things that I did in the first movie, but then to hear about fifty minutes to an hour of new music in it. It’s important to have the continuum in that particular sense.

In “Batman and Robin” the temp score was “Batman Forever”, so we knew where the themes from “Batman Forever” were really working great and where you’d want to hear them again. I think it was also on Joel’s wish list to direct this film even more like a comic book, even more disposable culture. More Wham! Bang! Pow! The hope when we were working on it was that it would come across that way. I think though in retrospect that some of the casting wasn’t perfect and maybe some of the storytelling could’ve afforded to have more content.

You must have written a huge amount of music for this score. Can you give my any idea of how much there was?

However long the movie was is the amount of music in it. Everybody worked on overdrive. By the end of the movie I was totally exhausted. One night my agent had Ennio Morricone over for dinner. Ennio and I ended up having a few bottles of wine and telling jokes till the wee hours of the morning. I had to go back and work at three o’clock in the morning and then I had a session the very next morning at nine.

Let me put it to you this way: I don’t usually like morning sessions because I end up working all night when there’s the least bit of distraction. I’d be on the scoring stage from 9:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. After that I’d play for the director everything we did on the scoring stage balanced with the picture; those were usually very emotionally draining moments. Then about 6:00 p.m. I’d go back and work on the mixes from the previous day. Around 8:00 p.m. or 9:00 p.m. I’d have dinner for an hour; then after dinner I’d have to compose till 6:00 a.m. when they pick up the scores. This is when Bob Elhai was working his ass off. Finally I’d go to the scoring stage with about two hours of sleep. This went on for weeks. Afterwards I had to go straight to New York to rehearse “Othello”, which was premiering at the Metropolitan Opera House, the day after scoring.

Do you think that current-day pop or rock suffocates film scores and their releases?

I don’t see how much more expensive it would be for them to just have a double CD or have the orchestral music on with the rock music. It’s greed from the individual artists, the artists’ managers, as well as the record companies that prevent it.

At one point when I was doing “Demolition Man” the lawyers from sting demanded that I can’t use “Demolition Man’s” original art on my CD. They said, “You can’t use it.” Of course, that will help me sell CDs, but everyone knows that Sting needs money. His management insisted that I couldn’t use the art and that my “Demolition Man” orchestral soundtrack was not released until a month after the release of their CD, so that they wouldn’t lose any money because they need money. That happens all the time.

Then there’s also the CD of “Batman and Robin” with pop music that’s ‘inspired by’ on it.

It was ridiculous! In “Batman and Robin” ninety-nine percent of the music on the album was not from the movie – ‘inspired by’ the record deals made my greedy producers. It’s sleaze ball. This is the one negative thing that’s ruining people’s appreciation for a great art form, which is scoring for films. It’s an art form which has only existed for a hundred years now, or less – that’s all. If you take the history of art in total and you try to add up a percentage of how much art is worthy of standing the test of time, it only has about a five percent ratio. I’m submitting to you that five percent of film music will be great music – just as much a ratio as music or art in any other form! So to deny listeners, enthusiasts, bugs, all these people an album like “Batman and Robin” is a shame. They promised me there would be an album too.

I thought your score was the highlight of the film. Why wasn’t it released?

They didn’t want it to interfere with the marketing of the pop CD. That’s it!

Note: Early in 1997, Schumacher was coronated 'ShoWest Director of the Year'. The March 6, 1997 edition of The Hollywood Reporter (vol. 345 no. 26) was a special issue about him. Goldenthal took a quarter-page advertisement as pictured above. This, of course, all happened before "Batman and Robin" was released to wide derision.