Robert Townson, producer for Varèse Sarabande records, discusses his job. He finances re-recordings of classic scores and has a good relationship with Jerry Goldsmith as conductor. Approvals, re-use fees, cover art approvals, and production snafus are all obstacles to overcome in record production.

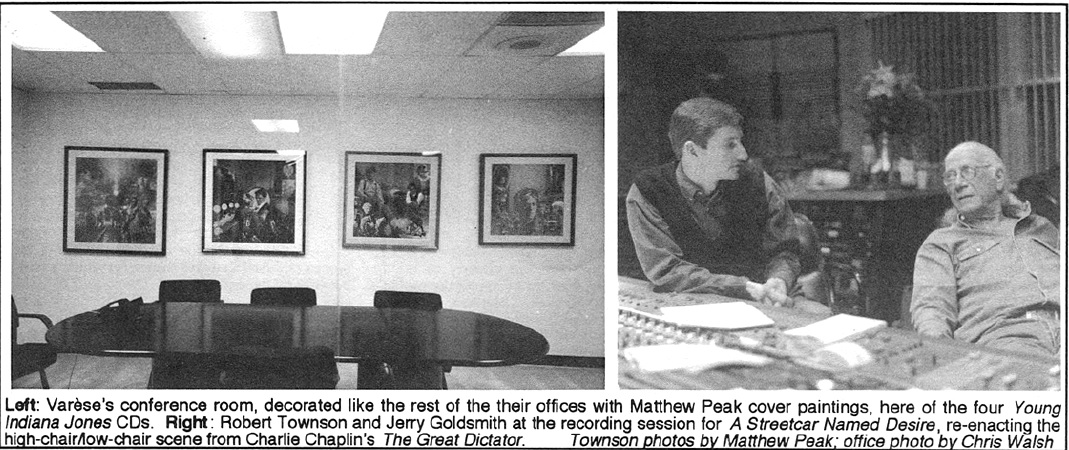

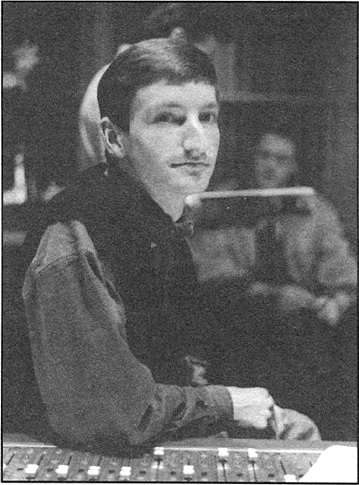

Let it be known that Robert Townson is a die-hard film music fan. That he is a hard worker is obvious from one look at any of our CD shelves, but the executive producer of Varése Sarabande’s soundtrack releases and re-recordings has a driving enthusiasm for the field that helps him to slog through all of the production tsuris. Townson is both a fan and good friends with many practitioners of the art, he often uses the words “very cool” to describe the music (“[‘To Die For’] is a very cool score, by the way”) and he is continually working to release as much good film music as Varése can afford. On the 12th of July I spent an hour and a half with Townson at the Varése offices, centrally located on Ventura Boulevard in Studio City, CA. We spoke during a lull in that day’s game oh phone-tag between Townson and Jerry Goldsmith, as they worked to schedule more sessions with the National Philharmonic in the fall. Townson’s enthusiasm was bubbling – in fact, contrary to my expectations, I was the more reserved one – as he showed me the art for upcoming CDs, let me listen to some of the re-recordings of “A Streetcar Named Desire”, allowed me to look at a copy of the CD “Jerry Goldsmith: Suites and Themes”, and generally acted personable. He closed out our talk (an hour of which I got on tape) by saying, “I gotta go. I have a hundred soundtracks to produce.”

Your re-recordings have really picked up in the last few years, but when I listed the ones that have been done so far, other than the Alex North series, I couldn’t sense if there was a direction in which you were taking them. Is your work with the Seattle Symphony going to result in more recordings?

Certainly. Not necessarily with Seattle, but they are one of the orchestras I’ve worked with, and there are just a lot of albums which I’ve backlogged over the years. Between Cliff Eidelman and Joel McNeely and obviously Jerry Goldsmith, I have a conducting team I feel good about. I like how they work with the orchestra, how they interpret the music they’re given. I mean, Jerry Goldsmith is brilliant with Alex North, and with anything he touches, and I think that’s resulting in a pretty historic series of recordings. And the younger guys, Joel and Cliff, are just remarkable. I feel comfortable with giving a Bernard Herrmann score to them; they’ll come up with an interpretation that I’ll feel good about.

How did you start to deal with Eidelman and McNeely as potential conductors?

I worked with them initially as composers, by producing albums of their original scores. With Cliff, the first was “Triumph of the Spirit”; with Joel, it was through “The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles”. I worked with them on those albums, got to know them better, got to know of their aspirations and talents, and so I wanted to give them the chance to step in front of a symphony orchestra and do something other than a score for a new movie.

In a report we had in FSM about a Goldsmith concert, Goldsmith said that the re-recording of “A Streetcar Named Desire” came about because of a free weekend. Exactly how quickly did that session come together?

It came together very quickly. It wasn’t just a case of Jerry suddenly having a free weekend and us saying, “Well, let’s do something.” We had been planning on doing “Streetcar” for a long time, and our first run at the album came the previous summer, but between “The River Wild” coming out of nowhere and the fact that his schedule is always in a state of evolution, we ended up not being able to do it. And then all of a sudden, in mid-January, again his schedule was changing, and something happened on a film that he was supposed to be scoring [he bailed from “Babe”, the talking pig movie- LK], and he came up with some time. [At first] it was almost a joke more than anything else, in that essentially we were talking about recording something the following week, on an album for which I had not prepared any music, hadn’t booked an orchestra, hadn’t booked a recording studio, so we just let it go at that, but he jokingly said during the conversation, when we were talking about trying to book this at some point, “Well, I’m free next week now.” Anyway, the next day he was off, he had to go out of town, and that was the end of that. But later that night, and the next morning, I’m thinking, “Oh, that would be so cool to somehow put together the “Streetcar” music.” So, just out of wanting to see what could happen, I made some calls to try to locate what we would need.

As it turned out, there were no conductor scores available. A lot of parts did exist, but only as reduced piano parts. But anyway, through the Warner Bros. music library and through Anna North, we gathered together most of the parts of most of the cues of the score; there were a few things decaying that we would need to re-copy, but essentially it was in pretty good shape. I then got in touch with Sidney Sax, and he kind of magically, over the next couple of days, came up with a studio and an orchestra. So I called Jerry, who was in Budapest at the time, and told him that we were ready to record the following weekend, if he was available – and he was up for it!

We sent him the scores for him to study while on the plane to London; we recorded only days later. Everybody mobilized for something we all feel very strongly about, Alex North’s music, and it was a magical recording – with two weeks of planning. Compared to “2001”, which was like three years! It turned out perfectly, a wonderful recording and we had a great time.

Also, Alex North had done some pre-production work on a disc for “Spartacus”. What can you tell us about those plans?

My intent with Jerry is that we’re going to record a lot of Alex. I mean, we’re just getting warmed up here. He was the most magnificent composer, who wrote so much phenomenal music, and he was a friend of mine and of Jerry’s. “Spartacus” was originally going to be the first album that we’d do, then of course that turned out to be “2001”, and then “Streetcar” came together, so I figure if “Spartacus” is not the next, it’ll be done within the next couple of recordings. It’s my favorite score, and to do a new recording of 70 minutes of it, with Jerry conducting, would be magnificent.

North picked his favorite parts of the score before he died; he essentially put together the album for us. He presented his 70 minutes, saying “this is how I want “Spartacus” to exist.” He was very aware of the recordings we were about to do, which would include at least “Spartacus” and “Cleopatra”, and we were already well underway with “2001” when he passed away, so he knew that all that was going to be, though he didn’t live to see it.

I was wondering if you could describe the process of turning a score into a score CD, a process fans hear about piecemeal; we do hear about specific problems, like the re-use difficulties that “Dolores Clariborne” had, resulting in 30 minutes of a 100-minute score being released, and we hear about the production of big projects, such as Fox’s “Star Wars” box set. But Varése does so many of these albums a year; how would you characterize the process?

To this day, when I finally hold a score CD in my hand, I see it as nothing less than a miracle – and that’s after 350, almost 400 albums I’ve done at this point. The number of obstacles you must overcome to produce a soundtrack for a new film, or to put a re-recording together, can make it just an incomprehensible undertaking. When people run down to their CD store and buy something, they have no idea what is actually going into it. When you have reshoots on the movie going on, and the composer doesn’t know what scenes are being changed while he’s writing the music (which he’s supposed to be recording the following week), and we want the album to be out before then to maximize its sales (since the album always has to pay for itself) – you end up with schedules that are just inhuman, and that are totally unrealistic for anyone to work under. It’s ridiculous for a composer to be put in that situation, but as ridiculous as it is, it’s not uncommon at all. It just happened with Basil Poledouris on “Under Siege 2”, it happened with James Newtown Howard on “Waterworld”, and “The Net”, which Mark Isham scored – it’s opening in a couple of weeks, and he just finished the recording last week [the first week of July] so we’re just starting to work on the album today.

So for all of these things to come into place for the original scoring session, while the composer is simultaneously trying to mix the score for the movie and for the album, while we’re working to sequence the album and put together a product and get the artwork from the studio…

We also have to get approval from the stars of the film – we’re doing a film like “The Net”, and all of a sudden Sandra Bullock of all people has approval of every image of her that’s distributed by the studio for the promotion of the film – so that takes time, to track down these people in order to get them to sign off on the use of their likeness on everything. With all of this going on just in order to create a releasable item, it’s why there are often no liner notes; in reality, there was like a day and a half to put a product together.

We do what we can, and if we have a director who’s in town and working with the composer wand is ready to do something extra, that’s one thing; it was nice to have Steven Soderbergh write something for “The Underneath”. But sometimes the director will already be off on location, so he’s unable to write anything, and the movie’s still being edited so you can’t see it and write anything about it, and the score’s being recorded while you’re working on the package so not even the music is done so that you can write about it. Just the whole last-minute nature, the complete flying-by-the-seat-of-your-pants process of production, stands in the way of albums existing in a way I’d like them to exist. You do what you can, but that’s as far as it can go sometimes. But in spite of all that, I’m very happy more often than not with how things turn out. I’d rather have a nice, representative 30 minutes of a score that’s well-produced and reasonably well-packaged, than to have something not exist at all. That’s the option. We just can’t take an extra month or two to do a “2001”-type package, with tons of photos and liner notes; we can’t have a longer album if it ends up not paying for itself, which would then ultimately reduce the number of albums that can come out. We have to be part of the real world, and live with budgets, and try to preserve as much good music as possible.

The 30-minute albums are difficult for the composers, too; we don’t inflict 30-minute soundtracks on everyone just because we like 30-minute albums, there’s just no option. It’s a difficult situation all around when someone has written a score that he or she is really proud of – “I think this is the best score I ever wrote!” – but if it’s 60 or 90 minutes long, and we have to pare that down to 30 minutes, it’s painful. But it has to be, because the dollars are too significant.

[And with reissues of older material,] the state of certain things can be pretty mind-boggling. For a long time we were going to do an album of Alex North’s “The Penitent”, a score that was recorded in the late ‘80s – and the tapes were lost! So you have Alex North’s second-to-last score, from 1987, but apart from a couple of cues that exist, the majority of master tapes are just gone. How sad that is; it’s such a wonderful score, but once the tapes are gone, they’re gone. It’s lost music.

If people knew the number of albums that almost happened, but didn’t happen – it dwarfs the number of albums that exist, because all of a sudden, for one reason or another, you run into a road block that you can’t get past. As disappointing and depressing as that is, sometimes you just have to pull the plug.

Kendall reminded us that that very nearly happened on the “Star Wars” box set; the only “Empire” tapes they could find were disintegrating, and that score’s only 15 years old.

It’s unbelievable how regular that stuff is.

How many CDs does Varése do every year now?

We’re probably still averaging 50 to 60 soundtracks a year, which is pretty outrageous.

I noticed that Varése’s tendency to give composers prominent credit has extended to putting the composer’s name over the title of the film on those labels on the new CD seals, the ones that are longer and easier to open. I thought that was a good call.

Yeah, I like those as well. It’s no secret that composers are at the heart of what we do here, which explains the prominent cover credits that everyone receives. We do larger composer credits than most other labels do. We want to treat the composers with the respect they deserve; we want to treat the recording sessions as events, which is what they really are. You have Jerry Goldsmith recording his new score, and that is an event. That is worthy of having Matthew Peak do artistic photo coverage, he’s not just somebody doing snapshots. It’s an opportunity to preserve what is a historic moment, when you have this wonderful music being heard for the first time. Imagine if we had photos, the kind of coverage we had in the “Rudy” and “Angie” booklets, for the early Korngold sessions, or for Alfred Newman’s, how wonderful and historic that would be. It’s a shame that it didn’t happen more often, then or now.

Explain Varése’s Vintage, for people who might not know what that is.

Varése’s Vintage is not something I work on, but it is a division that specializes in older pop albums. There’s also the Varése Spotlight series of Broadway recordings. They’re small subsidiaries; we’re all under the same roof.

What are your definite CD releases for the rest of the year?

There’s “Under Siege 2” with Basil, “The Net” with Mark Isham, “To Die For” by Danny Elfman, the Tangerine Dream score to “Legend”… we’re doing a Universal movie called Babe, Cliff Eidelman’s rejected score to “The Picture Bride”, which is a wonderful, beautiful score, a picture called “Magic in the Water”, with music by David Schwartz, a Hercules album with Joe LoDuca, “Sudden Death” by John Debney, a collection called “Voyages: The Film Music of Alan Silvestri”, that will have “Romancing the Stone” for the first time, plus a collection of themes from all of the other albums we’ve done with him; and then, of course, “A Streetcar Named Desire”, which is a very time-consuming project. And we’re getting ready for some more recordings this fall.

Is most of the mixing and mastering for your albums done at a certain dedicated studio? How much of it is farmed out to other studios?

Most of my albums, 70% to 80% I’d say, are mastered at Ocean View Digital. My engineer is Joe Gastwirt; he’s wonderful at what he does, and given a choice, schedule-wise, he’s the engineer I’d want to work with. As far as the recording goes, there’s a handful or studios around here: the Todd-AO scoring stage, which is conveniently right across the street, and that probably supplies half of the score. And then there’s the Sony scoring stage in Culver City. There used to be a lot of recordings done at Fox, but not anymore; they shut down their stage, which is unfortunate, it’s a wonderful room. In London, Whitfield Studios is wonderful, that’s where we did “Streetcar”; we did “2001” at Abbey Road, which is magnificent; and Joel McNeely just recorded his new score at Air Lyndhurst Studios, and he was really happy with the acoustics there.

One soundtrack I was curious about was “The Cowboys”. Specifically, some people were wondering about the use of a Bob Peak painting [“Before Winter”].

Bob Peak did not do that painting for “The Cowboys”, but I thought it was so perfect and appropriate for that album. I guess it’s no secret that Bob Peak is my favorite artist [gestures to the Bob Peak original hanging in his office], and he had a lot of gallery paintings that he had done over the years. [“Before Winter”] being one of them. The “Obsession” CD cover also was a Bob Peak gallery painting that had nothing to do with the film, but I don’t know if you could find something that evoked what Herrmann was doing musically the way that painting does. “The Cowboys” was an opportunity to expose a painting that people hadn’t seen before, which is very exciting for me. Hopefully such efforts are appreciated. I just love the way the package for that record came together.

What else can you say about your relationship with Bob and Matthew Peak?

I got involved with Matthew through his father. Originally I didn’t even know that Bob Peak had a son who was a working artist. I had had Bob do a painting of Jerry Goldsmith for the Suites and Themes disc that I did at Masters Film Music up in Canada. At the time Varése was wanting to have an original painting done for the “Screen Themes” disc [the John Scott performance of music from 1988’s films], but couldn’t afford to have Bob Peak, this internationally renowned artist, do the cover. This was around the time Matthew had done the painting for “A Nightmare on Elm Street IV”, so when I saw the ad for that movie in the paper, I saw that while there were a lot of rip-off artists working in a Bob Peak style, this painting has something different going for it. It was definitely Peak-inspired, but it was a lot deeper than that. So when I looked into this artist – remember, his paintings then were only signed ‘Matthew’ – and found out that his name was Matthew Peak, all of a sudden the puzzles pieces fell into place, and it was, “Oh my God, that’s Bob Peak’s son!”

So Matthew was hired to do the cover for “Screen Themes”, and the Miklós Rozsa “Hollywood Legends” disc. By now, we’ve done over 20 projects together. I think that, artistically, he’s developing at a phenomenal rate; he’s also a brilliant photographer, and that was just a sideline for him. He was never a photographer per se, he’s an artist, but he started coming to recording sessions like “Rudy”, “Angie”, and “2001”, and taking shots. It adds another dimension to things, to have great music and a great album, it complements it so much to have a great cover, one that’s done just for that music, a piece of art inspired by the music on that album. It really helps to make it a complete package. Like on the “2001” album, we have music by [dramatic pause] Alex North, conducted by [another dramatic pause] Jerry Goldsmith, art by [still another dramatic pause] Matthew Peak – what a team.

One of the great stories I love telling is about the film “Rich in Love”, which was Georges Delerue’s final score. When it was time for me to produce the album, Georges had already passed away. He was a good friend of mine, and he’s always been one of my favorite composers, so I wanted this final soundtrack album of his to be treated with great respect and dignity, and be very classy. But MGM had done this ad campaign that was just horrific – a bad graphic of a heart with a Band-Aid on it. It was really depressing when that came in. After the artwork arrived, I got a call from [“Rich in Love’s” producer] Lili Fini Zanuck asking what I thought of what they had sent over. I told her that I wasn’t excited at all, and was really disappointed, and didn’t like at all the idea of having that on the cover of Georges Delerue’s last album. Lili and I had worked together on “Driving Miss Daisy” and we knew each other by this point, so she wanted me to be happy with it. She said that she didn’t know what we could do here, but I suggested that we have Matthew do a couple of sketches, and have him do something special just for the album. She agreed to that.

Over that weekend, Matthew did four colors comp sketches that he worked on while listening to the score, so they were pieces of art directly inspired by Georges’s music. He shot transparencies, and we sent them off to Lili and Richard Zanuck, who were then at the Tokyo Film Festival. I got a call at home one night from Lili, and she said that all four of Matthew’s sketches were better than all 150 of the campaigns that MGM had put together for the film, and that she had already called the studio and asked them to postpone the movie’s release, because she wanted Matthew to redo the whole campaign for the film! He was hired by the studio to do a finished painting of their favorite of the four sketches he did. This was really the first case where the film’s ad campaign grew out of the score. His art is on the poster, on the laserdisc, and on the CD, and so because of wanting a good package of Georges Delerue’s music, the entire ad campaign of the movie was affected. It was one of the things that ended up bringing down the whole MGM art department! They were fired a couple of weeks later.

Tell us about Matthew Peak’s publishing company.

Sanguin Fine Art has been formed to print and produce notecards of Matthew’s and his father’s artwork. The Masters Film Music Fine Art Gallery, along with Sanguin, is going to do a whole line of posters as well, and I think there’s going to be some really exciting stuff. When, ultimately, the gallery is opened, there will be hand-signed photos, original prints, session shots, cover art like for “Blood & Thunder”, “2001”, “Fahrenheit 452”, “Days of Wine and Roses” [the Michael Lang-Henry Mancini album], plus his gallery paintings, plus his father’s work, which is an extraordinary number of great paintings that, for the most part, people have never seen. That’s the fun stuff, exposing Matthew to a wider audience, and doing the first albums for composers like Eidelman and McNeely – to take people whom you feel strongly about and do what you can to make people notice; hopefully they’ll feel the same way.

Best of luck for all this.

Thank you.

In closing, is there anything in particular you wanted to get published? An opinion, a feeling?

When I ready some of the magazines that report on this stuff, it just seems that so many people come at this trying to be as negative as possible about everything, and that’s depressing, considering how much hard work goes into them. Reviews are reviews, and not all of the work is good, but it’s too bad that there seems to be a negative tone over things; too many people have stopped trying just to enjoy what should be a great hobby and great music. But regardless of how it turns out, we’re always trying, the composers are always trying. If the composer has two weeks to write a score, obviously he’s not going to write “Spartacus”.

I don’t know, I just think people should try to have a little more fun with this, because I’d say that for the most part we’re having fun. I mean, it’s a great thing to so into a studio with a hundred-piece orchestra, even for Jerry; I still see him when he starts a new movie, and he’s excited by the challenges, he can’t wait to solve the problems inherent in it, deal dramatically with what he has to deal with, and write the best score he can. Every one is the first one again, because no film is the same. The first day in the recording session, when you’re going to hear this music for the first time, the composer’s there, the orchestra’s there, the director’s there, usually having an anxiety fit, nervous as hell, but then you get the downbeat, and if you have someone like Jerry at the podium, it’s just glorious. Like at the “Rudy” session, when Rudy himself was there, he had been told by the director that, “all this pain, all this anguish, will all be worth it when you see Jerry Goldsmith raise his arms in front of the orchestra.” And that was the perfect thing to say, because by the end of the playback of “The Final Game,” Rudy was in tears, the director was in tears, the orchestra gave Jerry a standing ovation, and it was a great celebration of great music that Jerry had poured his soul into. And he’s been doing that for decades. That, more than anything, sums up the state of film music. We have some great artists working, and it’s an exciting time, more so than it was five or six years ago, when there were fewer albums coming out (though I think that it’s gone too far the other way; probably there are too many albums coming out).

It’s 1995, and Elmer Bernstein is working on the biggest films, along with Jerry Goldsmith and John Williams, plus we have this great group of talented composers who are really busy these days: Hans Zimmer, Basil, McNeely and Eidelman, and Tom Newman of course writing brilliant stuff – and with this re-recording series that Jerry is doing, we know that every time we go to London, it’s a historic thing. It’s an exciting time for us and for film music.

Thank you for your time.

My pleasure.