The film music critic discusses his entry into the world of film music, writing magazine articles and learning to enjoy modern music. He complains about how no one watches older movies, and how CD labels don't care enough about the current music they license anyway.

Royal S. Brown is a familiar personage to those whose love of movie music ranges anywhere from fond appreciation to burning obsession. For 25 years he has been a prestigious music critic providing analysis and opinion on motion picture scoring, from his articles and reviews for High Fidelity in the early 1970s; through insightful commentary in his liner notes for Entr’acte albums and other recordings; to his interviews and column, “Film Musings,” currently published in Fanfare; and now, with his book Overtones and Undertones, published last fall by the University of California Press.

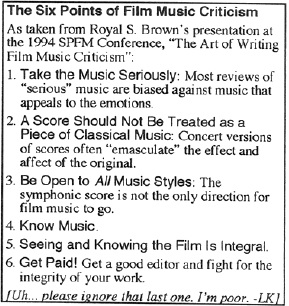

Those who attended last year's Society for the Preservation of Film Music (SPFM) conference got a chance to see him in action. His presentation during the workshop on “Effective Writing About Film and Television Music” was a highlight, as was his Morricone tribute presented later on. His lectures approximated the tone of his columns: anecdotal, free-flowing and extremely detailed in musical and film knowledge.

The following interview took place last October, shortly after the release of his book. Currently Professor and Chair of the Film Studies Program at Queens College in New York, Mr. Brown was gracious enough to spare a few moments to provide the same strength and clarity of thought he puts into his writing, but for free in an interview. One hates to make comparisons, but it would not be out of line to term him ‘the Harlan Ellison of film music’.

I was interested in interviewing you because when I first got intrigued about film scoring and started looking for material, in addition to Christopher Palmer's writings were your articles on Herrmann. I'd like to know more about your background: what brought you into music criticism and film music?

Well, they’re somewhat two separate stories. I started playing the piano at six and I got a degree in music from Penn State, but then went on and did my M. A. and Ph. D. in French. I’ve studied piano all my life; my degree at Penn State was actually in piano. I studied with a man named Barry Brinsmaid, and also with Thomas Richner for one summer. So I’ve always had this love of music and reasonably good training in its technical aspects.

One of the composers that I really didn’t like initially was Shostakovich. My father was always sort of an anti-dissonance man – he loved Cole Porter, things like that – and I sort of acquired an anti-dissonance snobbery, and thought that I didn’t like Shostakovich. It was funny, because there was one piece of his that fascinated me (the second movement of the 9th Symphony) that I’d heard on some crappy little Saturday morning sci-fi TV show; for some reason they were able to use it, probably illegally. Much later, when I was at Penn State, I found out it was Shostakovich’s 9th. The student union had these listening rooms that you could take records in and listen to them. I got – I think it was the Efram Kurtz recording, which plays the movement at a ridiculously slow tempo. That was one of the first Shostakovich recordings I ever bought and, all of a sudden, decided that I did like him. I think I got into it a little bit through Bruckner and Mahler and stuff like that. A friend of mine and I, who had sort of vowed in high school never to soil our ears with contemporary music, had a parting of the ways because I was sort of getting into it.

I took a course at Columbia University, when I was doing my Ph. D. in French, in contemporary music with Otto Luening. I wrote a long paper for him, which could have probably been a book if I'd finished writing it. Shortly thereafter, I'd heard that Morton Gould was going to record the (Shostakovich) 2nd and 3rd Symphonies; the 2nd I found totally fascinating in particular, having looked at the score. I sent to High Fidelity a piece that I had written about the Symphonies. The music editor at the time, Peter G. Davis, asked me if I'd like to do a future review of the Gould recording on RCA, and said, “Absolutely,” much to the chagrin of a staff member who thought that he was going to get the chance to do it. I had never been published in a magazine like that before; I think the only things I had published were a few articles for the American People’s Encyclopedia and stuff on French literature. And I was sitting in High Fidelity’s offices saying, “Gee, am I going to make $5,000 on this? Am I going to make $500? This is great; I'm writing for a big magazine. ” And, of course, they pay me $50 for it. [laughs] Sort of the big waking-up that I had in my life that you're never gonna make money in journalism unless you're… I don't even know who could possibly make money in journalism. We would get paid $50 for feature reviews and $10, if we were lucky, for regular reviews. I will say, for that time, they paid relatively well: $300 for an article.

But that’s how I started in High Fidelity – I was doing two or three, sometimes more, classical reviews – this was in 1968. It did not help my career as a college teacher; they looked very down on their noses at the fact that I was writing for a popular magazine. I had to get my various promotions on appeal – my tenure I had to get on appeal, and then it took me forever to get promoted to Associate Professor; it was only because of this book that I finally got full professorship. They hated that fact that, first of all, I wasn’t writing on French literature in which I’d be examining the use of the third person singular in Sartian literature dealing with lice [laughs]. I had a career in which I was not producing the kinds of articles for journals that got read by three people to get promoted and tenured.

Queens College sent me over to France for two years to run the City University program of study abroad, and right about the time I was getting ready to leave, word came out about the Bernard Herrmann recording of Hitchcock scores. High Fidelity had, at one point, done a few film music reviews; they’d stopped doing them. Peter Davis, not so much because he was against film music but because he just didn’t want to be bothered having to set up a new type of heading for the magazine, sort of said, “Well, no, we don’t really…” but I managed to talk him into it, and, as they say, the rest is history. I reviewed the album, “Music from the Great Movie Thrillers”, a title which I think he [Herrmann] had to use because Hitchcock wouldn’t let him use his name on the album, or something like that. I mean, it was really, totally stupid.

That got me started writing about film music for High Fidelity, and there was immediately a very good reaction to it. Somebody wrote in on “how wonderful that you’re letting somebody interested in contemporary classical music write about film music, because this is the only way it’s going to be taken seriously,” and then I did a really large piece on film scores, in which I not only covered the classic stuff, but also went into Pink Floyd's music for “More”, and stuff like that. I got some really angry, “How can you possibly mention Bemard Herrmann and Pink Floyd in the same breath” letters after that. I kept writing on film music in High Fidelity until I left the magazine in 1979 because the new music editor, Kenneth Furie, was just editing my copy to death; I went over to Fanfare and did film music reviews for them, and seven or eight years into that, we started doing the column.

1970 was really a turning point in my life because not only did the Herrmann album come out and the writing for High Fidelity start, a man named Harry Geduld got me to put together a book of articles on the French filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard [published by Prentice-Hall, 1972], and that got me really thinking about film. Now, when I look at the kind of writing I was doing back then, even though I still have a lot of the same points of view, I was terribly naïve about the more technical aspects that were going on in the cinema, and those I’ve just simply picked up on my own by reading about films since then.

I’ve always loved movies; I’ve been a movie buff all my life. I sort of got academically into movies via film music, and into film music both my love and my knowledge and study of music as well. That was the combination. Even when I was seven or eight years old, I would always come out of the movies talking about the music, and nobody would understand what I was talking about. I’d say, “Boy, I really liked the music for that film,” and they’d look at me, “There was music? We didn’t hear any music. ” Well, I did, and I liked it, and I wanted to have a recording of it. One of the big thirsts that I had was in 1958 after seeing “Vertigo”; I was dying to get the Mercury recording of the score, and I think it took me two years to track it down. It wasn’t widely-sold.

It’s hard to judge now, but I guess recordings then were extremely hard to find.

Some of them were impossible to find. The marketing was just terrible on them. I think I actually found “Vertigo” in a department store – department stores used to sell long-playing records, believe it or not. I was expecting to see this spectacular cover, maybe using some of the Saul Bass graphics from the title sequence. And instead, it’s this ridiculous Kim Novak-Jimmy Stewart thing.

That cheesy looking photograph.

Not quite as bad as the reissue on Mercury. The photographer got this fairly ugly-looking wife of his and did a kaleidoscope type thing; it's one of the great ugly album covers of all time.

About the book: I was impressed in how well you encompassed pretty much everything in covering the evolution of film scoring, including rock, which is rarely touched upon. The bit about “Head” [1966 The Monkees film] was surprising.

That was funny, too. In the heading for that chapter [“Music as Image as Music: A Postmodern Perspective”], I originally had a quotation from that sequence, ‘The War Chant’, as part of the chapter heading and within the text. The people who give out provisions for that wanted $500, and would not relent. I had to cut it out of the heading and paraphrase it in the text, which was a shame. I can’t believe, for a university press book, that they would stick to $500, but they did.

I'm really glad the book ended up the way it did; the University of California Press was absolutely wonderful to work with – I think they did a great cover. They let me write my own book. The first reader was Claudia Gorbman; she had a lot of important and good comments to make, some of which I followed and some of which I didn’t. Bottom line is, I was at liberty to pretty much make it exactly the way I wanted to.

What reaction have you gotten since publication?

I've gotten very positive reaction; I haven't gotten any negative reaction so far. There's a professor, Ron Sadoff, who teaches film music writing at NYU who is using the book (as a class text). Nick Redman reviewed it for the Director's Guild of America publication.

I think that one of the things that helps the book is the fact that I don’t have the prototypical academic-jargon type of style, even though I think my points are as deep and possibly even deeper than some of the points that are made in texts that should sound as if they should be a lot deeper. I have a reasonably accessible style, though I do have a knowing tendency of putting parenthesis within parenthesis and writing sentences that are a page long. [laughs]

It's interesting that in the last few years, starting with Claudia Gorbman’s book, there seems to be a resurgence in academic studies of film music.

Yeah, absolutely. Because Claudia’s book, there’s Kathryn Kalinak’s book, and [Caryl] Flinn's –

Strains of Utopia?

Yeah. And Martin Markshas a book coming out soon [Music and the Silent Film 1895- 1925, to be published by Oxford Press]. Finally, good old death Academia has realized that movies have music in which the kinds of political, sexual-politics and psychoanalytical readings that you get from looking at the visuals and the editing and the narrative texts can also be enhanced by knowing what's going on in the music. Claudia’s book was the first; she's one of the major people in the area. There's also Fred Karlin’s book [“Listening to Movies”, Schirmer Books,

1994] which is somewhere between academic and popular, which I think is very good.

I don't know what's going to happen after this, but I'm really glad to see it happening. It would be fun if, somehow, this kind of material could be presented even more popularly, whether on television programs or something in that area. It’s becoming a very popular subject – there’s no shortage of people who are interested in it.

I wanted to get your perspective on something. There's been an ongoing dialogue in the past few issues of FSM about a substantial amount of the readership’s lack of knowledge of the “classic” scores and composers and that there’s very little appreciation of that era.

I just find it appalling that they're opening 70-plex movie theaters all over the place and not even in one of the 99 theaters they've got in these ugly buildings, with these teeny screens and ridiculous seats, can they show old movies. Even if you look at something like American Movie Classics, how many really important films with the good Erich Komgold scores are they showing on that? There's an appalling lack of interest [in the past]. I'll give you an example – I have a Ph. D. student of mine who's teaching a course at a local college. She wants to show some of the older films, foreign films, and stuff like that, and there's practically a revolt in her classroom – and this is college level! Students saying, “Well, we liked ‘The Color of Money’, but even that was too long. ”

Basically, what they want are films made in the last, shall we say, ten minutes that are no longer than 90 minutes. In color. And, in English. And preferably with Amold Schwarzenegger, I presume.

See, I personally feel that, even though the “Star Wars” music is good clean fun, ultimately, I think that John Williams really set back the cause of a genuine interest in film music. I mean, it never fails—whenever I start off a class or give a lecture on film music, almost the first thing I do is play the opening of King’s Row, and I ask, “What is this?” And inevitably they say, “Superman”, “Superman II”, “Superman 10. ” Never met one person who has gotten that it’s Korngold’s “King’s Row”. Not one. Not one. I find it deplorable, particularly since these are really good movies. We're not talking about stuff that is better off forgotten, or even about the most spectacular ones like “Double Indemnity” or “The Sea Hawk”. Things such as “The Big Combo” (scored by David Raksin) or Fritz Lang's “While the City Sleeps”, a lot of the Samuel Fuller films, the Joseph H. Lewis films (“Gun Crazy”), all the ‘B’ films which are just fascinating visually and musically. It's just absurd, and I think it's totally encouraged by the type of marketing done these days. All that people want to see and hear is the most recent film and the most recent film score.

And then it's forgotten: “Okay, you've seen it, it’s past; on to the next thing. ”

Right. What if we had this idea towards Shakespeare? We'd never see Hamlet again; all we'd go to see would be the most recent play that was written. With literature, we read old books – well, actually, a lot of people don't. It doesn't seem it’s quite as bad in the older arts, whereas in cinema, the whole idea seems to be that we're actually going to keep these old movies out of the theaters. Unfortunately, people are so brainwashed that, if you were to show a wonderful, brand-spanking new print of “Double Indemnity” at your local 90-plex, no one would go to see it.

Even then, when you think that, gee, colleges can make in-roads and stuff like this, you get the stories of my doctoral students who can't even get these kids to see Hitchcock, for heaven's sake. They don’t want to see a black-and-white Hitchcock film. They want to see a 90-minute film made 10 minutes ago. It’s horrifying. I think the TV critics who, in one- or two-minute sound bites, basically praise or trash a film depending on whether or not it has a believable storyline are doing enormous harm to the film-going public. Fortunately, we have a Leonard Maltin around who will remind people that films were made more than five years ago.

It's really depressing, but I see a few hopeful signs. Even though it doesn’t have an original score to it, at least theyre able to sell well a movie like “Pulp Fiction”, which I think is a brilliant film. People aren't totally caught up in seeing movies like “Speed” and “True Lies”, and crap like that. There are some good films being made and even getting audiences.

What other projects do you have coming up? Any more liner notes?

They don’t come to me too often anymore. As I'm sure you're aware, this is another area that desperately needs improving. Very few of the film music recordings have notes. Some of the ones that are coming out now I could have done notes for, but in one instance I managed to piss off a conductor named Adriano who thinks I destroyed his career from what I understand –

I’ve written fairly often about Franz Waxman at John Waxman’s request and I think I would've been asked to do the notes for “Rebecca” if Adriano hadn't been so down on me.

Then there’s the Silva experience. When they came to me to do the notes for Howard Shore [“Dead Ringers”], they said, “Well, we'll give you six free copies of the CD. ” I said, “You know how many CDs I’ve got sitting around in my house? I don’t need CDs, I need money. I won't

Do it for less than $300. ” There was a lot of mumbling and grumbling, and it was finally Howard Shore himself who paid me the $300 out of his own pocket. That's where the CD industry is at; they won't even pay an established writer money to do some deep, probing notes on the music of one of the major film/music collaborations that’s existed in the last 20 years. The composer had to pay me. It’s really stupid.

I have an article coming out in Cineaste called “Film Music: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly”

[Vol. XXI Nos. 1-2, with a large film music supplement section], in which I sort of light into “Gone with the Wind” for various reasons and “Star Wars”, and there's an article fora film history compilation published by Oxford University Press. Another thing I'm working on; the SPFM is doing an oral history project, and I'll be doing an oral history of John Barry for the Society's archives. It's not firmed yet, but hopefully within the next year or so, it'll happen.

Other than that, I'll keep writing my column and planning my next film-related book, which will be more involved with overall structures of mythic/musical narrative cinema.