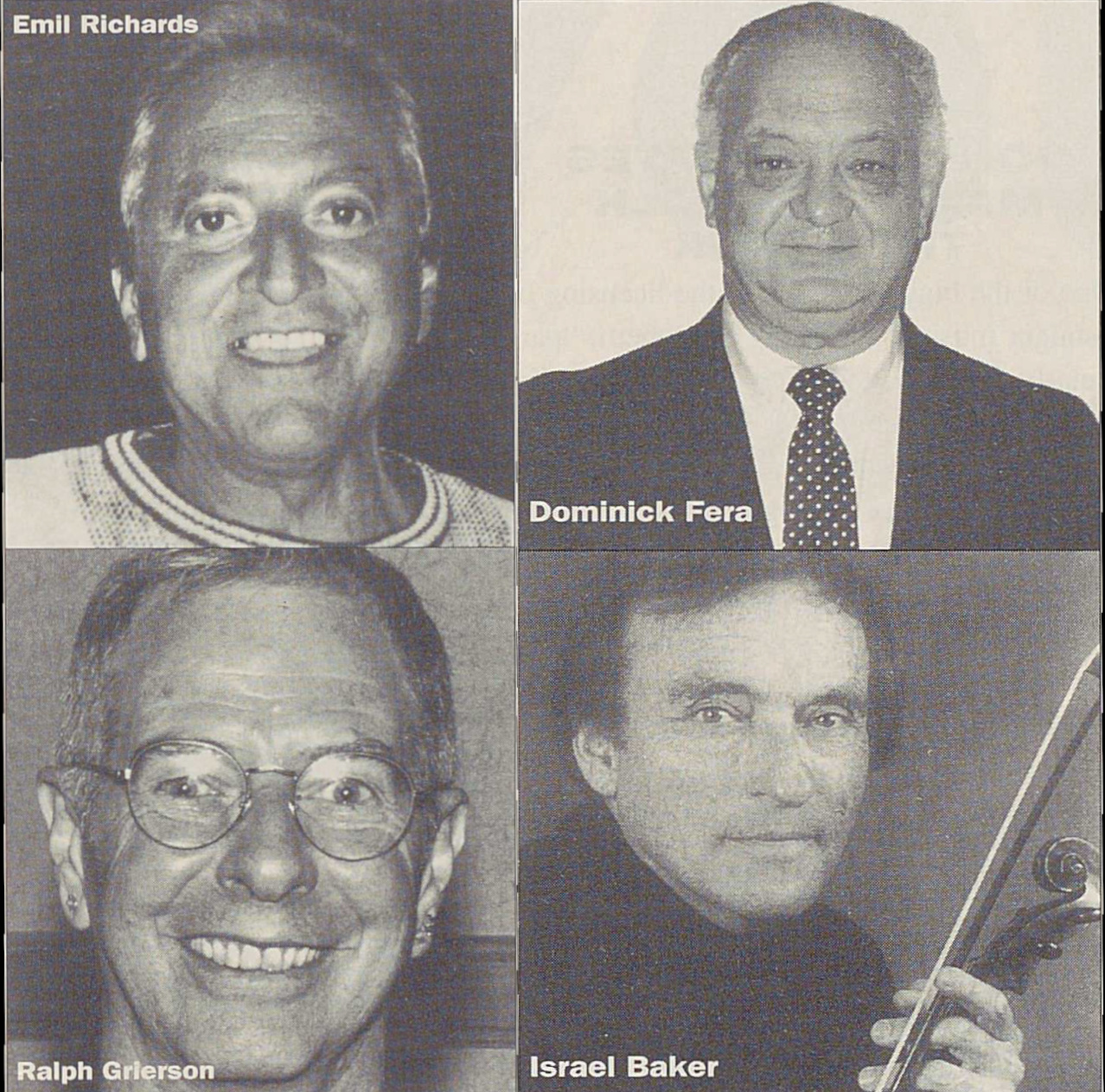

Musicians Emil Richards, Ralph Grierson, Dominick Fera, and Robert Israel discuss their perspectives on film music. Richards wants more screen credit; Grierson wants more musicians on movies. Fera wishes that it was like the old days where you got a job by being part of a group, and Israel stresses the importance of good sight-reading.

They are filmdom’s most unheralded artists. Though the best of them do as many as 50 films a year, few outside the business know their names and they rarely get a screen credit. And yet, movies are unimaginable without them.

They are Hollywood’s top musicians, a pool of some 500 string, keyboard, woodwind, and percussion players, as well as other artists. They give life to the work of film composers, and their playing underscores everyone’s favorite screen moments from the kiss to the pratfall to the chase.

Here are some of the best…

Music makers in Hollywood never look in the Yellow Pages for drums. They simply call Emil Richards.

Richards, 62 (who was born Emilio Radocchia) is not only a peerless percussionist; he also has an astounding collection of 650 rare and exotic percussion instruments that he has gathered from around the world. From the time Boston Pops conductor Arthur Fiedler discovered him in the tenth grade playing xylophone in the Hartford Symphony Orchestra, Richards has been producing memorable sounds from a variety of percussion instruments.

He has played alongside Bobby Hackett and Charles Mingus, George Shearing, Stan Kenton, Count Basie, George Harrison and Ravi Shankar, and Frank Zappa. He has recorded with Perry Como, Ray Charles, Judy Garland, Bing Crosby, Doris Day, Nat “King” Cole, Sarah Vaughan, and others.

On a world tour with Frank Sinatra in 1962, Richards began to explore and collect percussion instruments. Every movie composer from Elmer Bernstein to Bernard Herrmann to Henry Mancini to Lalo Schifrin has called upon him since then. “Major composers really do their homework,” Richards says. “If a movie’s set in Vietnam or Africa, the composer will do work on indigenous music. That’s when they call me.”

He keeps his instruments in a warehouse, complete with catalog, and charges studios a cartage fee for their use. Some composers are overwhelmed by the array of choices. “I can boggle a composer unless I pin him down,” he says. “They have to be specific.”

Richards carts 12 trunks of instruments to recording sessions, and he takes pride in creating new sounds. With wife Celeste, he has produced there books for children showing how music can be made using kitchen and backyard implements.

For the big chase scene in “Planet of the Apes” for composer Jerry Goldsmith, Richards simply struck the bottom of stainless-steel mixing bowls. “I got calls from all over about that,” he says, “people wanting to know how we did it.”

For the 10-minute fight scene between Mel Gibson and Gary Busey in “Lethal Weapon”, composer Michael Kamen told Richards: “I want you to catch every hit and punch.” Richards used Chinese, German, and Swiss gongs, anvils, and a brake drum to underscore every blow.

“Michael took the 10 minutes and scored the entire 100-piece orchestra to these rhythms,” Richards says. “And, bless him, he gave me that cue as a credit, which means I get ASCAP royalties.”

Credit – or the lack of it – is one thing that bothers Richards, who won the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences (NARAS) Most Valuable Player Award so many times – six – that they retired his number. In 1994, he was also inducted into the Percussive Arts Society “Hall of Game”, joining such names as Buddy Rich, Gene Krupa, and his early idol, Lionel Hampton.

“How many times have you heard a solo in a movie and wondered who it was?” he asks. “But musicians never get their names on a movie’s credits. They say credits are too long already. But the honey-bucket man gets his name up there, and the limo driver.”

One threat to classical musicians that has diminished, he says, is the use of the synthesizer. Though very popular in the ‘’80s because producers, especially on television, thought a synthesizer would save them money, “now it has taken its place as just another member of the orchestra,” Richards says. “It hasn’t taken over, which we were afraid of. Even keyboard players felt it was overkill. And the thing that saved us was the kids. They got tired of drum machines. Now they’re playing live too.”

Ralph Grierson, 52, who is an expert on keyboards from the piano to the harpsichord to synthesizers, agrees that the synthesizer has found its proper role.

The Canadian veteran of hundreds of movies says: “The ideal way to look at it is to consider an organ with a flute stop. It doesn’t work. You can use a synthesizer to replace an orchestra, but it doesn’t sound like an orchestra. It sounds pretty cheesy.”

Grierson has performed with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, played at Carnegie Hall, the Monday Evening Concerts in Los Angeles, and at the Ojai Festival. He lists among his recordings an album with Michael Tilson Thomas of Stravinsky’s ‘The Rite of Spring’, and he’s also a recipient of the NARAS Emeritus Award for receiving several Most Valuable Player honors. His experiments in electronic music include several years with the L.A.-based group Ishtar.

Still, Grierson favors big music for movies. “Film is a larger-than-life medium,” he says. “If you don’t have a large orchestra, then you don’t have the sense of hugeness that movies are famous for. You want to be swept away. It takes huge forces to do that, to set the emotional tones. The more colors, the better.”

Like most musicians, Grierson seldom sees a credit, but that’s his piano solo on the etude that John Williams wrote to follow the huge orchestral climax of “E.T. The Extra Terrestrial”. He can also be heard on James Horner’s score for “Field of Dreams” and in Johnny Mandel’s “Being There” music.

For all his success, Grierson sees “ominous overtones” in the current state of TV and film music. “Composers are under an awful lot of pressure,” he says, “and they’re now being given packages out of which they must pay musicians. The temptation to go to (non-union) Utah or Munich or London is great.”

He’s proud of the Los Angeles musical community. “The orchestras here are so good,” he says. “They intuitively know how to play with each other. The way you phrase something, all the unspoken things that aren’t even notated – that just happens.”

Clarinetist Dominick Fera, 68, looks at his 42 years in the film-music business and at the many hundreds of movies to his credit and wonders: How the hell did I do it? Some kind of luck.

It was more than that. Born in Italy and the son of a tuba player, Fera grew up in Pennsylvania not far from where Henry Mancini was turning into a useful flute and piano player. They were both taught by Fera’s father’s cousin, Joseph Faga, and later would work together in the movies.

After graduating from Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute of Music, Fera came to Hollywood and was soon established, playing on Victor Young’s score for “Around the World in 80 Days” and Elmer Bernstein’s for “The Man with the Golden Arm”. He was worked with every famous composer since.

Fera is a classical clarinetist (“I’m a long-haired musician,” he says) and does not get called for jazz or rock. “You get pigeon-holed,” he admits, “but there has always been a lot of work. When rock came, a lot of the great composers were getting older, and producers went to younger people. But tastes change, and the requirements for film have changed. There’s much more demand for symphonic and structured scores again.”

A veteran of many orchestras and a teacher, Fera remains pleased with the quality of the Hollywood musical community. “The competition is fierce, and the standards are high,” he says. He regrets that networking is essential to getting work today. “In the old days, you belonged to a certain clique or group, and you all worked for one composer,” he says. “Today, everything is freelance; everyone’s a social butterfly.”

In the studio-orchestra days, there were strong musical directors with a staff of composers with strong backgrounds, Fera says. “There is a hell of a lot of raw talent around today,” he adds, “but they have no place to develop.”

The studios gave Fera more than just music, however. At the RKO recording studio he met Marie, his wife of 37 years and an accomplished cellist who works regularly in film. “One of my first gigs was an Ida Lupino picture with music by Ernest Gold,” he says. “I carried Marie’s cello into the studio. Six months later we were married.”

Violinist Israel Baker, now in his 70s, has seen it all since he was named concertmaster at Paramount Pictures in 1952, but he’d seen a lot already.

Having picked up a violin at the age of 4 in his native Chicago, Baker went on to become one of the NBC Symphony Orchestra’s youngest players under conductor Arturo Toscanini.

Baker has been the soloist with orchestras from Toronto to the Hollywood Bowl. He was concertmaster for Bruno Walter and Igor Stravinsky on all their Columbia Records work in L.A. He has played with Jascha Heifetz and Gregor Piatigorsky, Glenn Gould, Yaltah Menuhin, Andre Previn, John Williams, and many others.

“Heifetz once gave me a new piece of music and said, ‘Play this.’ I didn’t make a mistake in two pages,” Baker recalls. “He was surprised, but I’d learned with Franz Waxman. Good, trained musicians can sight-read. You look through it once and play.”

In Hollywood’s contract years, every studio had an orchestra, although musicians could also freelance. “It was a handsome salary back in the ’50s at Paramount – around $200 a week,” says Baker, who has worked with every top film composer you can name, including Bernard Herrmann on the celebrated string score for Hitchcock’s “Psycho”.

Baker can be seen briefly playing a Chopin solo in the movie “Harlow”. For “The Balcony”, Baker and his fellow musicians recreated Stravinsky’s ‘Histoire du Soldat’ in a live recording at a motion-picture studio. “The reviews were great,” Baker says. “Critics said it must be a phonograph record. It was so good. They said we’d be mentioned in the movie’s credits, but they forgot.”

Baker has got a full credit, however, for his work on three Chuck Jones “Cricket” cartons. “Mel Blanc did the voices, and I played the violin – Mendelssohn, Tchaikovsky. I loved it.”

His one regret has nothing to do with the movies. In 1950, Baker purchased a Stradivarious violin for $18,000. Ten years later he sold it for $23,000. “I offered it to Isaac Stern for $25,000, but he said that was too much,” Baker recalls. “Today it’s worth $1.5 million.”