Advice on how to acquire expensive needle-drops for your movie.

The 1990s are turning into a boom decade for nostalgia music. From “Forrest Gump” to “Sleepless in Seattle” to “Dazed and Confused,” already proven music golden oldies from the record bins of destiny is doing double and triple duty for filmmakers. Such prerecorded music saves the trouble and expense of hiring a film scorer to write new tunes and of recording them with a huge and expensive studio orchestra. It shoulders a second burden of transporting the audience immediately to a remote time and place. In addition, it can form the core of a soundtrack album, which in turn may create more revenue than the movie itself. But before you, the film director, rush off to your bin of old CDs, LPs, tapes, 45s or 78s, you must beware. You’d better have a license. And thereby hangs a long list of dos and don’ts from experts in the music-licensing field. Here are a few:

Tutti Frutti? All-a-Rooty. But Remember the French Connection.

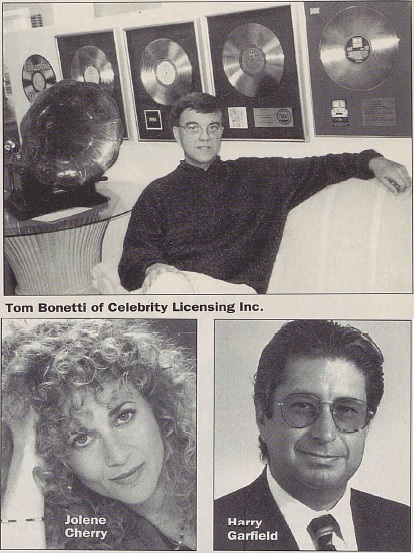

Although it’s true that such American artists as Little Richard and Elvis Presley signed away their rights to their hits in this country, such laws don’t apply in France. There, ‘moral rights’ legislation does not recognize such a practice, warns Tom Bonetti of Celebrity Licensing, one of the leading firms in the field of nostalgia licensing. So if you have a big scene in your picture where the kids are dancing to ‘Tutti Frutti’ and you want to play your picture in France, be prepared to pay extra to Little Richard, because he’s still going strong.

Don’t Let Pirates Make You Walk the Plank

“One of the biggest pitfalls in the licensing of nostalgia music,” according to Bonetti, “particularly the stuff we recorded prior to 1972, which is not subject to U.S. copyright, is that a lot of people are running around, marketing or licensing rights that are bogus rights that really don’t exist. Some of these are just outright forgeries, fabricated documents that someone created from scratch. But a good percentage of them are from these so-called tax shelters of the 1980s, where certain rights were licensed or even sold, in some cases, for the specific limited purpose of these tax shelters.

“Normally they had a life span of seven years. They were for the United States only, and so what the thieves did, they just tore up that page, and substituted a page saying nonexclusive perpetual worldwide. So you can wind up putting something in a movie licensed from a thief and the rightful owner will come and say, ‘Take it out of the movie, or pay me X hundreds of thousands of dollars.’ It can cost you millions.”

Know Your Basics

There are two types of licenses: The sync license is sold by the publisher of the song, and the master use license is from the record company that owns the rights to a performance recording. Per sync or per master, the average price for film licensing is between $7,500 and $15,000. Some songs or performances are higher. Usage counts. For main and end titles, for instance, it’s much more expensive.

Do Start Licensing Early

Bones Howe, an independent music supervisor who formerly headed the music department at Columbia Pictures, cautions that “you have to begin checking things before you shoot.” If the songs are written in the script, we check on them right away, because often times a whole scene will be built around a piece of music. If you can’t clear it, you gotta make a substitute fast.”

Howe, who supervised the music on “Buckaroo Banzai” and the first “Back to the Future,” was one of the pioneer practitioners in this complex and subtle field nearly 20 years ago. In addition to his ‘do’, he has an important ‘don’t’, and that is...

Don’t Bother the Boss

Howe, a jazz aficionado, says this facetiously, but the meaning is serious. Bruce Springsteen is “the one that everybody wants, but nobody can get,” because, like the Beatles, “he’s really expensive.” And in a similar vein:

Don’t Expect ‘Georgia on My Mind’ for $5

Brady Benton, assistant manager of television and film licensing at peermusic, helps music users access a catalog that contains more than 250,000 copyrights.

“A lot of times they will want a really, really popular song and expect to get it for virtually no cost. They always say ‘We have next to nothing to spend.’ But it just doesn’t work that way. ‘Georgia on My Mind’ is a huge song and instantly recognizable. To be able to license that, you have to be able to pay for it.”

And you can’t say, Benton cautions, “‘Well, OK, we’ll use ‘Georgia’, but we’ll just play it in the background very low, so no one will hear it.’ That still doesn’t work. You can’t get away with something like that.”

Do Give the Expert the Chance to Help

“It would be very nice,” Benton says, “if they would allow us sometimes to say, ‘Well, let me send you a tape of other jazz-type things that might work in the scene. Let me know what the scene is about, and let’s see if we can find something in our catalog that’s a little older or not as well- known that I can give you for the money that you’re talking here. But you can’t have “Georgia on My Mind” for $5.’“

Remember, You Can be Talking Big Dough

If you go to license a George Gershwin song or a Cole Porter song, it could be $25,000 to $30,000, Howe points out. “That’s just to license the song, and then you gotta go looking for a recording of it. And if it’s Sinatra or somebody like that, it could be another $30,000 or $40,000. And you could end up spending $100,000 to put one song in your movie for a minute.”

Let the Experts Save You Money

If you’ve got something at Universal Pictures, for instance, Harry Garfield, senior vp motion picture music, creative affairs, has ways to help you shave costs.

“If they come to me and say, ‘We’ve gotta have this song,’ and I go to the people that have that song and it’s $50,000, and they go, ‘Oh, my God, we can only pay $5,000,’ I’ll go to some publishers and say, ‘We want a song that has the same feel as so and so. For $5,000 what do you have that doesn’t get used all the time that will do the job?’

“I’ll go to several people and have them pitch to me, and I’ll bring it back to the client. In other words, I’m making the publisher or the record company pitch the song and be a part of the creative process. That’s one way to get it cheaper.”

Fit the Music to the Scene

A man who believes in spending money but spending it wisely is Michael Lloyd, the former A&R vp for MGM Records. Lloyd was the music supervisor for “Dirty Dancing” and its all-time best-selling multi-artist soundtrack album.

Lloyd advises filmmakers to avoid spending a lot of money on incidental music, which doesn’t further the script.

“What you’re making is a motion picture,” Lloyd says. “So just as you would like to have good photography, good actors, a good script all of those kinds of things just as the importance of certain scenes may require complicated shooting to get all of the nuances on the screen, the same is true of music.

“You may have certain scenes that require, really demand, a certain song or artist. You need to concentrate on that rather than to just try to get a bunch of music in. It’s important that you pick and choose where these songs are going to go so that they actually help the picture.”

Jill Meyers of Jill Meyers Music Consultants handled the music licensing on “Forrest Gump” as well as “Ready to Wear” and “Speechless.” The former job is described by Howe as “a nightmare” involving more than 50 songs from many different sources and with many different artists. Her advice is:

Think Package Deal

“If you go to one publisher and use several of their songs in the picture, they will often give you a package price. And if you’re trying to get something less expensive especially if you’re willing to use contemporary music you can go to a publisher and say, ‘What’s a new artist that you’re trying to get exposed that you can give me a good deal for?’ And sometimes they’ll couple some of their lesser-known things with something that’s a little bit better known for you.

“The other thing you can do,” adds Meyers, “if you don’t want to pay for the record, a lot of publishers will have new songs, and it’s to their benefit to get them exposed. So they’ll give you very inexpensive prices and let you use demo masters of their own that are record-quality demo recordings.”

Don’t Blow the Stuff Once You’ve Got It

That’s the advice of Jolene Cherry, who was music supervisor on more than 20 films including “The Crow” and who now has an exclusive production deal with Atlantic and various other Warner Music Group labels.

After you’ve got the sync rights and the masters’ rights, she advises, “Hire a music editor, the person who physically cuts the music into the film. This is an important function if you have serious music in a film.

“The music editor is key in cutting and placing the tracks, and because of their depth of experience regardless of whether you hire a music supervisor a good music editor can be invaluable in terms of knowledge and technical advice, especially if you are shooting on-camera music sequences. They can make the difference. Music that is well placed and well cut is every bit as important as a good film editor.

“It’s an exciting time” in the music licensing field, Cherry says, “because directors understand music more, and the audience is very savvy about music. So, hopefully, the days will soon be numbered for the old-fashioned director who thinks there’s no room for source cues in a film.”