Money is getting tighter for television music budgets, and synthesizers have been replacing real musicians. Composers share their thoughts. Dennis McCarthy says that package deals, wherein the composer pays for the music from his own fee, naturally leads to lower investment in live musicians. Laurence Rosenthal believes that producers don't understand that you can pay for a small orchestra instead of a large one. Mark Snow believes that one live musician can single-handedly 'save' a synth score. Patrick Williams gets by using synthesizer, but only because he has such strong experience with live musicians in the first place.

The orchestral television score is rapidly becoming a lost art. Only a handful of weekly series continue to use a primarily acoustic ensemble, among them “Murder, She Wrote,” “The Simpsons,” “seaQuest DSV” and the “Star Trek” series.

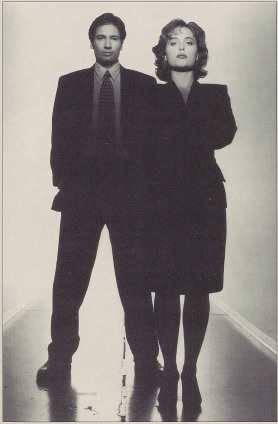

Many use a combination of acoustic players and synthesizers as a means of combating ever-shrinking music budgets, and several (such as Fox's “The X-Files”) use electronic music exclusively. Telefilms are no different: Most combine acoustic and electronic sounds, and a number are all-synth scores.

Has the overall sound of music on television suffered as a result? Most veteran composers say yes, although a growing number of composers (mostly younger) defend the use of electronics as frequently appropriate for use artistically as well as economically.

Producers are reluctant to talk for the record on the subject. As holders of the purse strings, they fear being depicted as the villain in the acoustics-versus-electronics debate. Admits one Emmy-nominated producer of network-television movies and miniseries: “You can go to a lot of trouble to get a lot of beautiful music, and by the time it comes over that box (the home set) it doesn't sound very good. So you say to yourself, Why spend the money?”

Dennis McCarthy has won Emmys for his work on “Star Trek: The Next Generation” and “Star Trek: Deep Space Nine” and continues to conduct a 40-plus-piece orchestra every week – alternating as composer on both “Deep Space Nine” and the new “Star Trek: Voyager.” He explains how the current state of TV music evolved: “Over the years,” says McCarthy, “we've all seen the tremendous growth of sampling, synthesizer technology, computer technology, MIDI and everything else that has made it possible for anyone with a good musical ear to create a score just sitting at a desk.

“Producers found that they could offer less and less money for total scores. [When packaging started] you would use acoustic musicians and maybe have a synth in there. Pretty soon the budgets started to go down, and [composers] would say: 'Well, gee, I could probably beef up the strings with my synths. Let's go down to six violins instead of 12, and all the low strings I'll do on the keyboards.'

“The bean counters then said, 'Well, this guy says he'll do it for $1,000 less.' All of a sudden you're down to two violins and a synthesizer. Instead of having three trumpets, you've got one. Trombones took a hike a year earlier, and French horns are only a distant sound in the imagination,” notes McCarthy, who points out that he regularly uses several electronic instruments for their “specific, unique sounds” but that he also turns down requests to score TV movies solely with electronic music.

Five-time Emmy winner Laurence Rosenthal (“Peter the Great,” “The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles”) says synthesizers can produce sounds impossible for an orchestra. “In that capacity,” Rosenthal says, “I think [electronics] are unique, and I applaud any attempt to expand the sonic and timbral capacities of the orchestra by the use of newly created sounds that can be dramatic, expressive, unusual and powerful.

“But,” he adds, “I think that the aesthetics of synthesized scores are far less an issue with most producers than simply the fact that some guy can sit in his garage and crank out a score for synthesizer which will more or less do the job and which will cost [the producer] markedly less money.”

Much depends on the talent of the composer, says Rosenthal. “Some composers can really do such wonders with electronics,” he says. “You just say, 'Wow, what imaginative, effective sounds those are.' But most of the time, I'm afraid, it just sounds like a lousy substitute for real, humanly generated acoustic [music].”

Rosenthal, who has written massive orchestral scores for such television epics as “Peter the Great” and “Mussolini: The Untold Story,” ironically finds that he has been “miserably disappointed, very often, by the inadequacy of big orchestral sound, and delighted by a smaller orchestral combination.”

Declares Rosenthal: “It is pathetic the way [some] producers reveal their values by settling for a frequently inferior electronic score, compared to what could have been done, almost as cheaply, by a small and effectively used instrumental combination.”

Mark Snow has seen, and been a part of, the changing attitudes toward electronics. Fifteen years ago, he was scoring “Hart to Hart” exclusively with an orchestra. Now he creates the strange colors and textures of Fox's “The X-Files” every week in his home studio.

Snow also does an average of nine to 12 TV movies per year and says that combinations of acoustic and electronic sounds are most often desired by producers. “You have a bed of synthesizer [sounds] and three to five live soloists coming in. All you need is one live player whether it's a sax, a guitar or a flute, a real expressive instrument to take the curse off the machine quality of the whole thing,” he says.

Some music, Snow states, simply cannot be replicated electronically. An example is a John Williams score, which is full of contrast – loud and soft – and fast and slow – from one moment to the next.

But, Snow points out, that's not a particularly popular sound in television, “which mostly tends to be – I'd say 80% -- mystery-oriented music, even if it's a family tragedy or a disease-of-the-week [film]. There's always a mysterious quality to it all; that sparse, sustained stuff seems to be very much in vogue.”

Last season Snow scored “Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells AH” with a 55-piece orchestra. Now, for the same producers, he is completing work on “Children of the Dust,” a four-hour CBS miniseries with Sidney Poitier, Michael Moriarly and Farrah Fawcett. Although set in the Old West of the 1880s, the score, Snow says, will be an equal combination of Synclavier and orchestra.

Five years ago, despite having scored 80 movies and hundreds of hours of television (from “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” to “Lou Grant” and “The Days and Nights of Molly Dodd”), composer Patrick Williams feared that he “was going to have to get out of the business.” He thought, My day is past, because virtually all TV music was being packaged and because budgets were so low as to demand electronic augmentation of traditional acoustic groups. Williams has, in his words, “hunted and pecked” his way into familiarity with the technology, effectively finding “a new way to work, new ways to do the same old things that to me are exciting, new ways to use the technology that I find stimulating and different. I'm enjoying working again.”

Case in point: last season's Emmy-nominated score for TNTs “Geronimo,” which was a surprising combination of acoustic sounds and unrecognizably electronic ones. “I had a real string section,” Williams explains, “but we tucked some samples in there too. And it brought a scope and grandeur to the string sound that was really nice. And the high-tech effects, the samples that we found and ways we could use them ethnic [sounds], mixed with orchestra were fascinating.”

All his past experience “pays massive dividends in the use of the technology,” Williams says. “I feel that I'm a real composer in that sense, not a technoid.”