Video games are beginning to use recorded orchestral sound; Bruce Broughton was the first to score a game with full live music. Game company executives discuss using in-house vs. contracted composers, and how orchestral music will continue to make inroads into the video game industry.

Today’s interactive game has come a long way from the early days of cartridges. In some cases, these games have evolved into full scale interactive movies on a CD- ROM requiring the same creative approach as a motion picture. As a result, many film and television com- posers are now looking to branch out into this area as a source for work.

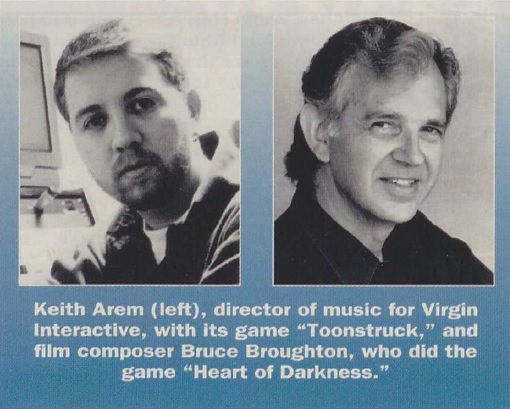

“Dating back to the beginning of video games, the industry wasn’t actively seeking composers as much as people who had a lot of technical knowledge,” says Keith Arem, director of music for Virgin Interactive, “so the music was done primarily by in-house programmers who knew computers but did not have a lot of music experience. Now, the interactive community has buckled down a bit. When I was hired by Virgin, they actually wanted a film composer to come in-house to do their music. I’m now setting up a lot of our affiliate labels to follow suit in the direction that we’re going, which is taking a lot of film techniques into the interactive domain.”

Entertainment industry talent is crossing over to interactive because the plat form is becoming similar to that which composers are used to working on, says Spencer Nilsen, director of music at Sega Music Group. “I guess it’s just like film was in the ’20s and ’30s,” Nilsen says. “It’s really the Wild West out there because the technology is always changing, so the creative requirements change each time as well.”

Peter McConnell, in-house composer/software designer for LucasArts, says having a film background can be a distinct advantage these days. “We’re aiming for sort of an interactive cinema experience,” he says. McConnell was co-developer of LucasArts’ proprietary iMUSE system, which allows for dynamic sound and music that reacts on the fly to player decisions. “What we really want to do is make it so that if you hear someone playing one of our games in the next room, you’ll think they’re watching a movie on TV.”

As a result of this film style approach, LucasArts and other developers are assembling their own in-house music departments.

“It makes a lot of sense for a company to have an internal department like we have because the teams can work directly with the composer,” Arem says. “You have access to the assets on a daily basis and as things change you have a first-hand look at it. But at the same time, a lot of companies don’t have the facilities or the backing to set up a department the way they want, so they’re forced to go outside.”

Take 2 Interactive of New York is one company that prefers to go outside for its game music. “We’re now finding a great abundance of people who are experienced at doing game music and they’ve all become pretty professional at presenting themselves,” says Michael Glorieux, executive producer of the upcoming Take 2 game “Ripper.” “We certainly consider people who have experience in film and video but we also draw upon the group of musicians who know what’s entailed in game development,” Glorieux adds.

Even Virgin Interactive opts to go outside sometimes. In what may be an industry first, Virgin brought in noted film composer Bruce Broughton (“Tombstone,” “Silverado,” “Miracle on 34th Street”) to do a full film-style orchestral score for their “Heart of Darkness” CD-ROM.

“The main reason I did it was because it was the first of its type,” says Broughton. “We did an orchestral score as if it were a motion picture and this was the first time, as far as we know, that this has been done for a game. Originally they were going to do the animated sequences with the orchestra and the game sequences with a synthesizer, but as things went along they decided that they wanted the whole thing orchestral. The only thing different from a movie is that I also gave them a few small pieces that they could use during the game for emotional support.”

Sometimes, original music, whether created internally or outside, is not enough. Take 2 contracted a classic rock song to be the theme of “Ripper.” “When we began ‘Ripper’ we were looking for some popular music that would give it a hipper attitude than the typical type of computer-generated MIDI music that usually accompanies computer games,” says Glorieux. “We all sort of fell in love with the idea of going after Blue Oyster Cult’s ‘Don’t Fear the Reaper’ because it perfectly fit the title and you could work with the plot of the song to go with the plot of the story. We’ve completed negotiations to license that song and are now in the process of getting the band to create some original music as well.”

For the outside composer, the process of breaking into multimedia music is the same as breaking into other areas of the business. Even for a seasoned professional, a little luck and serendipity goes a long way.

In the case of Broughton, the developer saw a film that he had scored. “The developer had seen an animated film that I did for Disney called ‘The Rescuers Down Under’,” he says. “They fell in love with the score, so they wanted a similar approach for their game.”

For former rock musician Thomas Dolby, who scored a major multimedia hit with the Interplay title “Cyberia,” entree to the interactive world was slightly different. “The way Thomas broke into it was by going to conferences and meeting the developers, which you could really do a year or two ago because the conferences were small,” says Dolby’s manager, Mary Collar. “Now the conferences have grown so large that it’s really difficult to meet the actual developer anywhere other than on a panel.”

Still others opt to try the time-proven method of sending tapes and presentation packages.

“I get literally thousands of tapes from everyone from 12- year-old kids who have done nothing but play games all the way through to the biggest artists and film composers in the world,” says Sega’s Nilsen. “They have a lot of different interpretations of what we do and what is needed. But that’s a good thing because there’s really no hard fast rules.”

And every once in a while a new talent does break through this way. “Through my relationship with Mike Varney at Shrapnel Records, I was listening to some of their new tapes and I heard this one guy who was made to write game music,” says Nilsen. “His name is Ron Thai and his stuff was not only compelling and powerful but also quirky and unique. We signed him up and five weeks later he had written 28 pieces of music for a project we just finished called ‘Wild Woody.’“

Arem also says that solicitations for work has become part of his daily experience. “We get about five or six calls every day from composers wanting to submit material and do work for us,” states Arem. But there are certain criteria that must be met before any serious consideration is given to an outside contractor. “An external contractor has to bring us a product on the level of what the best recording studios puts out. That’s what we’re looking for quality-wise.”

“In my mind, the interactive industry is trying to compete with the film industry,” says Arem. “That being the case, independent contractors are at an unfair disadvantage because unless they have access to the best facilities, it makes it harder for them to compete. A composer or production company that has its own facility has a big plus because they can give us the deliverables that we need so we don’t have to spend time in transferring them.”

Regardless if the music is done in-house or externally, the composer must be paid and that issue, just like the technology, is constantly evolving.

“In the past we’ve paid around $1,000 to $1,500 a track which is a buy-out,” says Arem. “For a musician, it’s not a great thing because there’s no publishing, mechanical royalties or residuals like they have on records and films. So for that kind of money, we know that we’re not going to get a John Williams.”

“In some cases it’s sort of like a sweatshop mentality,” agrees Nilsen, “but composers are getting much more savvy and much more aware of the financial potential of a hit. That’s why we’ve started our own record division, because it gives me the ability to say to an artist ‘Right, you get nothing on the game but we can now put out a soundtrack album where you will get full royalties’.”

How much a composer is paid depends on the approach, says Glorieux. “You can get a young hungry artist who hasn’t published anything before to do an entire game for under $5,000 and buy it out. But you can also go to people who will charge you much, much more than that and probably a royalty as well and then that becomes a whole new financial dimension.”

Of his experience in multimedia, Broughton says: “The money wasn’t horrible but it certainly wasn’t like on a feature. To have the opportunity to be on the ground floor was the main reason why I did it. There’s a really big question as to where this entertainment is going to go and right now everybody is very hopeful for it.”

But Arem says he sees the financial writing on the wall and the figures are going to get bigger. “I think that you’re going to see this industry change drastically in the next year or two,” he states. “I think you’ll see the unions and ASCAP and BMI come in, which may make it an advantage to have independent contracts rather than in-house staff because it may ultimately end up being cheaper that way.”