How various directors use music - source and score - on their films, and what makes for a good underscore.

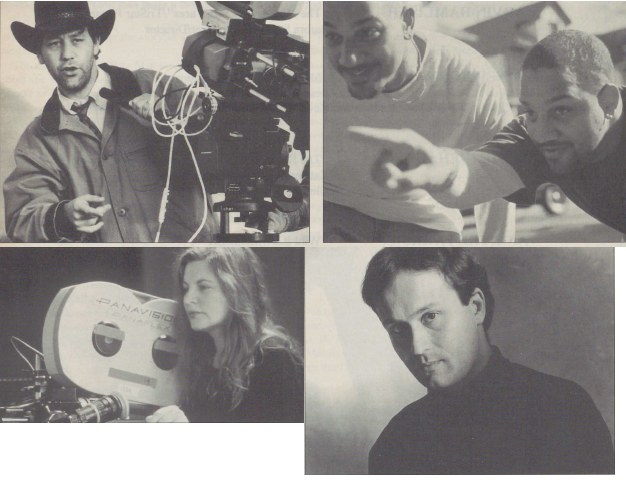

Sam Raimi

I think about music very early in the process. Once I have a script, I start thinking about what it's going to look like and close behind that I think about what it will sound like. Sound effects and music are, to me, literally 40% of the movie. I've seen movies absolutely not work until the soundtrack is applied. Like "Evil Dead" for which Joe LoDuca did the music. It wasn't a scary picture until the soundtrack came on. Likewise, "Darkman" was a miserable mess, but I was fortunate enough to work with Danny Elfman, a brilliant composer who gave it a heart and soul. For that movie, the music equaled the emotions. Danny made it come to life.

All the composers I've worked with have taught me a lot: Alan Silvestri on "The Quick and the Dead" and Joe LoDuca, my hometown cohort I've worked a lot with since 1980. He did "Evil Dead" and "Evil Dead II," "Army of Darkness" and he's doing the TV series I'm produc ing, "American Gothic" and "Hercules." I hooked up with Joe in Detroit. He was a jazz musician and had never written a score, but he made a demo tape that was great: frightening and strange, with chaotic sounds that spoke of dark forces lurking. I knew he was the guy. In a horror movie, for me, it's about whether the music is helping drive the scene, giving it emotions or insights. I sometimes make horror movies that deal with unseen things. Musicians can create music that gives this abstract evil a malicious, malignant personality, and creates a sense of doom.

Allen Hughes

In the two films we've done, music's been extremely important, a big emotional aid. It translates what you're trying to say to the viewer because you can feel music even more so than you can a visual. With "Dead Presidents," we had all these oldies we knew we wanted to put in before we started shooting. Two weeks into shooting everything was just hell, really hard with the crew and everything. I made up a bunch of oldies tapes: Isaac Hayes, Curtis Mayfield, Barry White. They had the vibe we wanted to get across. We gave tapes to all the actors and crew. From that day forward, I swear, everybody was happy. It was amazing what music did on the set alone. The film is set from 1968 to the early ’70s. In fact, the only reason the film goes into the ’70s is because we developed the script to make use of those untapped early ’70s oldies. It's always been the ’60s Motown sound in films.

On "Presidents," we worked with a composer for the first time: Danny Elfman. He does some things he's never done before, a really interesting mix of percussion, industrial sound and orchestra. We worked closely with him but mainly just told him what we didn't like. He taught us what music can do for a scene in terms of the score; he made some scenes 10 times more dramatic. We hadn't experienced that on “Menace II Society”. He showed us how powerful it can be.

Alison Anders

Music has been pretty important to me all along. My first scripts were music oriented. "Border Radio" was completely music-oriented; in fact the financing was secured because of it. I used [The Blasters'] Dave Alvin to score it. On "Gas, Food Lodging," I used [Dinosaur Jr.'s] J Mascis to score. For "Mi Vida Loca," I used John Taylor of Duran Duran to score. "Grace of My Heart" is a woman's journey from the late ’50s to late ’60s. It's about the suffocation of where you came from, finding your independence, your own voice, your own true self. I probably wanted to be a musician. But I had no style, no unique voice. My mother is an amazing singer-songwriter; my daughter ended up with some of that. I was just a fan.

Paul Mazursky

When I start preparing a movie and thinking about it, sometimes writing it, I find music to inspire me. I'll often play it while I'm writing and rehearsing. And I keep finding more. Sometimes I even hire the guy who wrote that music. So it's very key to me. Maurice Jarre did the score for "Enemies: A Love Story." When I showed him the movie I had in a temporary track of klezmer music and he loved it and was inspired by it too. I worked closely with him.

Now, on "Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice," the sort of theme song, ‘What the World Needs Now (Is Love, Sweet Love)’, was a hit before I made the film. We cut the final scene, the Fellini-esque ending where all the couples come out of the hotel in Vegas, to that song. And it was a sensation! It just took the whole audience to a perfect place for a difficult ending. I think I actually shot that scene playing the music. There was nothing like that first moment when we put it up against the scene and saw that it worked. When you like a song, and it works, you think they wrote it for you.

Mel Brooks

I’m really unhappy with what's happening to classic movie scores. They're being replaced by an assortment of collected standards. It's really depressing. I don't mind a song from the past in a movie, but that's not a film score. A score is what Bernard Herrmann did for "Psycho." I treasure film scores. One of the highlights of my life was John Morris's score for "Young Frankenstein." It is haunting and beautiful and perfectly captured the movie forever in people's minds. For me when a perfect score matches a perfect picture, it's seamless, you don't even hear it. Like heavenly music. It doesn't stick out. Just like you turned over a rock and it was always there meant to be. Then there's Hummie Mann, who did "Robin Hood: Men In Tights." He, like John Morris, understands that the score is never funny. It doesn't compete with the wit and comedy hijinx. It's a supportive element. If the score were funny it would cheapen the movie. It's begging for laughs. Hummie is now busy with "Dracula: Dead and Loving It." We're gonna have a big, majestic 1930s score; somber and riveting, and there won't be a standard in it. We have a waltz scene in "Dracula" and we're using a Strauss waltz. I picked that waltz. We were true to the Victorian era. That's another big mistake people make. You never have your composer write a Strauss waltz – only Strauss can do that, right?

Walter Hill

A score can support and underline the drama, which is, frankly, the role of the score that least interests me. Or it can surround your movie and provide mood without particularly underlining the drama. I like that approach better. I've worked with Ry Cooder a lot and he's as good at that as anyone. He did his first score for me on "The Long Riders," and he's gone on to make such a tremendous contribution to the language of film.

I work closely with composers; it's part of my job, I think. They know more about music than I do, but the movie talks to me and says "I need this, I need that." Ideally you've got a composer in mind before you even shoot your movie, and I like them to be very conversant with the script and have a long gestation period to think about the movie. It would make life easier if you could just turn the music over to a composer, but it doesn't quite work that way.

There's a particular problem attached to the film I'm about to do. We're using Kurosawa's "Yojimbo" as the basis of the story, but updating it to a ’30s American gangster story. The Manasan Sato score for "Yojimbo" is one of the glories of Japanese cinema. Then, of course, Sergio Leone did a knockoff of "Yojimbo" when he did "A Fistful of Dollars" and the Ennio Morricone score is legendary. Those are big shoes to fill. I'm happy to say that as big a challenge as it's going be for me, it will be equally big for the composer.

John Schlesinger

Music is vital. It brings a whole new perspective to every movie. Luckily, I'm pretty musical. Not a lot of directors are, and I've found it very useful. My favorite part of the whole process is postproduction, because suddenly you can see another dimension added to the movie when you hear the score for the first time. When we made "Far From the Madding Crowd," there was a scene which we had totally given up on, but Richard Rodney Bennett's music illuminated and changed the whole thing. Hans Zimmer did similar things for me on "Pacific Heights." And I'm very much looking forward to working with James Newton Howard on "Eye for an Eye." He's a big name, but doesn't do necessarily big scores.

I think sometimes Hollywood movies are over-scored, which doesn't always do justice to the film. Sometimes slighter scores can be better. Witness the zither on "The Third Man," one of the most innovative scores of all time. I think about the score early on. When Pat Metheny scored "The Falcon and the Snowman," he came to Mexico where we were shooting and we showed him bits of the film with another of his compositions on it. He started to put down possible themes, which he sent to us in Mexico. That's a wonderful way of working. Music is so important to me that I like to get the composer involved as quickly as I can.

Allan Moyle

Music is massively, awesomely important to my latest film, "Empire Records", which is set in a record store. The music plays all day. If it's not in your face, it's in the background every second of the movie. I like to score movies with songs. We'll find a piece of a song that will function as score. Even if we do need a little score, I like to go to a band to do it. We didn't need a composer on "Empire". We had an editor, Michael Chandler, who was totally into music. He was scoring the movie with fragments of songs all the way along and I loved that. Michael isn't a kid – he has teenage sons – but he listens to these left-of-center bands and he turned me on to some incredible songs.

On "Empire" we had a terrific music supervisor, Mitchell Lieb, who also did "Boys on the Side." He's really smart, and basically picked the Gin Blossoms song to be the hit single from the soundtrack. The movie isn't as angst-ridden as "Pump Up the Volume" (which didn't make any money) and the soundtrack's the same. So, whereas here we have the Gin Blossoms, on "Pump Up the Volume" the music was a notch darker. This is lighter, but the soundtrack is still terrific. That can't help but help us. I wanted to be able to consult at length about the music and the situation was perfect.

Carlo Carlei

I try to make my movies emotional experiences for the audience, with a balance between music and images. Music is more important than words to me, and I have fairly good knowledge of classical music. I met my composer on "Flight of the Intruder," Carlos Lioto, after I decided not to do the movie with Ennio Morricone. I wanted something new. Carlos and I seemed a good combination. We're both a little too romantic.

The way we work is. I try to give him the mood of the movie even before I shoot it. Then he sees the dailies and then my cut. He starts to think about melodies. I'm a very melodic person, in the direction of John Williams, John Barry and Maurice Jarre, and he knows that. When he has about 20 or 25 melodies, he plays them for me. We try to choose a main theme and decide where the other melodies will go throughout the movie. I'm heavily involved in this process and in the orchestration and the recording. It's absolutely important that I am, because the score is really the soundtrack to my dreams. And my collaborators at the end of the day have to make me happy.

There are directors who don't know anything about music and pre tend to be composers. I don't. I didn't study music. But I think I have a strong sensitivity towards it, so I describe through metaphor what I want. You have to use the skills of the talented professional you work with. I have to trust him. He has to trust me. That's why Carlos and I work well together.