Zimmer talks about his confrontational behavior with directors coupled with his inviting attitude towards up-and-coming composers.

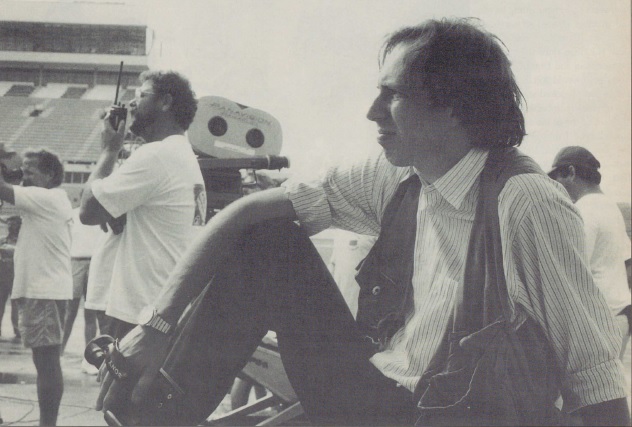

Hans Zimmer, whose “Lion King” score won a Golden Globe and an Oscar, may actually be the hardest-working man in show business. The 38-year-old German-born composer usually writes the scores for about a half-dozen films a year (though he’s been known to tackle 14), with a schedule so tight, he only left himself a month to score “The Lion King.” Other familiar credits include: “Rain Man,” “Driving Miss Daisy,” “Crimson Tide,” “Backdraft” and “Thelma and Louise.”

Born in Frankfurt and educated in England (with almost no musical training), Zimmer joined synth-pop group The Buggles in the late ’70s. Their hit ‘Video Killed the Radio Star’ was the first song broadcast by MTV. Appropriately, he’s been meshing music to images ever since, first with veteran film composer Stanley Meyers, and then solo. Here, he talks to Joshua Mooney for The Hollywood Reporter about technology’s impact on film scoring, working under the gun, life after the Oscar, and his innovative company Media Ventures, a studio/training ground/artistic community for film composers.

Do you remember the first film score that affected you?

“Once Upon a Time in the West.” It was the first ‘adult’ movie I saw as a child. First impressions last forever, and I thought, “Wow, this is what I want to do.” And [Ennio] Morricone is still one of my heroes.

Stanley Meyer got you your first film job, on Nic Roeg’s “Eureka.” It must have been an intimidating experience.

I remember sitting there and shaking. [I was] so nervous about Nic. There’s a scene where Gene Hackman finds this gold in the mountain and I said, “So Mr. Roeg, what would you like here?” and he sort of looked at me as if I was a complete imbecile and said, “The sound the of the earth being raped.” And I thought, “Yeah, this sounds like fun. I know how to do this.”

How has film composing changed in the years since?

Technology’s helped a great deal. I’m a lousy player but I know how computers work. I would not have a career without the computer. I have no musical education. Two weeks of piano lessons, that’s it.

What are the specific bene fits of all the new technology?

I’ve got so much equipment here I can fake up an orchestra completely. The benefits are two-fold. I can sit there with my big orchestra and get the colors right, integrated with the colors from the film. And then you get the director in and you can really have a good argument about every note. Because you’re not lying to him. You’re not saying, “Well that’s where the strings will come up,” while you’re playing him something on the piano.

Does technology allow you to work faster?

No. It’s exactly the opposite, because suddenly you have all these toys around and your imagination runs riot. I’m taking longer now than I used to just because the possibilities are truly endless.

At the same time, production schedules are increasingly tighter. Composers are expected to create ever more quickly.

Oh, it is impossible. I’m working on a film right now. We’re supposed to start recording next week, and they haven’t even shot the end of the movie. But the strange thing is, it somehow gets done.

You obviously have to be able to write quickly.

It doesn’t take long for me to write a film [score]. It takes endless time thinking about it, then passing through the intellectual stage. Because you can’t write intellectually. You have to write from that dumb place called the heart. All I try to do now is get involved at an earlier stage. I bug the scriptwriter as opposed to the director.

Is the rise of rock and pop soundtracks as a movie marketing tool doing damage to the art of film composing or to the movies themselves?

I don’t think people set out to damage their own movies. It’s an odd process making a movie. You eat, breathe, think, sleep with that thing and you don’t get any feedback from the outside world, and everything is a problem and somebody comes along and says, “If we put this song in, it’ll make the scene bet ter.” You suddenly see it as a God-given solution. And sometimes you see it at the premiere and you die.

I’ve noticed that your music seems well integrated into the films, as opposed to scores that can be manipulative and overbearing.

It’s that European thing. We think about film music in completely different ways. If you spot a film in Europe, you are very concerned about the places in the film where you don’t have music. Over here you don’t question that: the music starts at the beginning and ends way past when the cleaning lady has left the cinema.

What kind of responsibility do you feel toward audiences?

If you ask an audience what they really want to see, they’re likely to say something like “Batman,” right? And in a way they’re right. But I see my job as not asking them what they want to see but showing them something they can’t even imagine.

Is that also part of the process of working with directors?

Yes. The director will tell me what he wants and inevitably I go in another direction because I think my job is to surprise him. Otherwise, get yourself a musical secretary.

From your experience with directors, what are examples of a difficult situation and an ideal one?

The ideal situations are sometimes the difficult ones. One experience you’re going to think I’m totally crazy was “I’ll Do Anything” with Jim Brooks. Because we spent as much time playing with his pages and his movie as he was playing with me and my music. It was a completely integrated thing. And okay, nobody liked it. That doesn’t change that I had a good experience.

What about working with a powerful presence like Tony Scott on “Crimson Tide”?

Tony and I were arguing like nobody’s business. Inevitably one of us would storm out of the room and then come back in. But we wouldn’t have done it if we hadn’t cared. I really think that “Crimson Tide” is as much Tony’s score as mine because we fought about every note. We were sort of playing the movie out: he was Gene Hackman and I was Denzel Washington. I said to Tony after wards, “I’m sorry I put you through this. Will you forgive me?” And he said, “Forgive you? I’ve already offered you my next movie.” I need confrontation.

Is there a Hans Zimmer score you’re most pleased with?

I hate them all. Well, I don’t hate them all. I still like “Driving Miss Daisy.” I think “Crimson Tide” works. I think it goes against what you expect. This is not an action movie, but we made it feel like an action movie. Which is actually manipulation of the worst kind.

How has winning the Oscar affected your life and career?

I thought I was this guy who wouldn’t care, and when I stood on the stage I really did care. It was a revelation. Then it was a sort of closure. I’ve only been doing this for about six years and I’ve just managed to bring a career full circle. I can’t imagine that a second Oscar is as exciting as the first.

What, then, are your post-Oscar goals?

I’m running around thinking maybe I should try something completely different. I think success should buy you a license to go wild and crazy and do wacky things.

Which brings us to Media Ventures. What’s the idea behind your company?

Composing is lonely job. You sit in a room and the director comes in and beats up on you. What my partner Jay Rifkin and I did was build the studio and got all these composer friends of ours here. It’s like a ’60s commune in the ’90s or something disgusting.

What’s the main goal?

It’s about rattling the town a bit. I’m so bored with the idea that the same five composers get to do all the movies in Hollywood me included. So I’m trying to push other people who are really talented. Like Mark Mancina. We got him “Speed.” I was more excited at Mark’s premiere than I was about any of my own stuff. Another one of our guys, Jeff Rona, worked on “Homicide” and “Chicago Hope.”

You work as much as anyone in Hollywood. What have you done since “Crimson Tide”?

I went from “Crimson Tide” straight into “Nine Months.” I had two days off after that, and I started “Something to Talk About.” Next, I have a thing once a year where I want to do something for my seven-year-old daughter because “Crimson Tide” ain’t her thing. So I’m doing a Muppet movie, “Treasure Island.” And what could be better after a Muppet movie than straight into a John Woo movie [“Broken Arrow”]. I do try to keep it varied.