Has No Regrets

Ken Wannberg is music editor most prominently to John Williams. Wannberg discusses how he broke into the industry, how Williams likes to record and edit, and the increasing pervasiveness of temp tracks. Wannberg also discusses some of the scores which he was written himself.

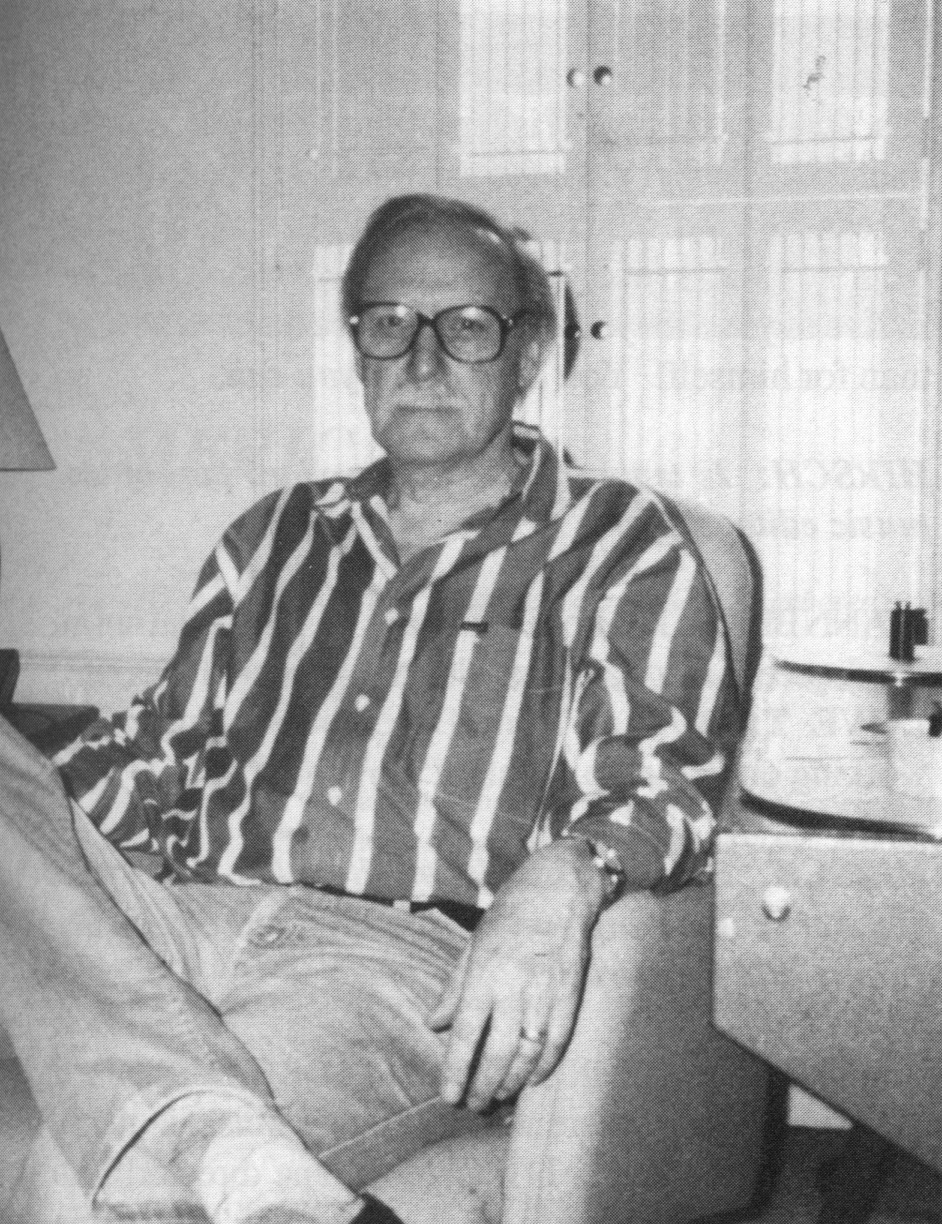

Without a doubt, Ken Wannberg is probably the most contented man in Hollywood’s film music community. A thirty-five year veteran, his knowledge and experience has touched on every facet, from spotting to temp tracking to scoring. Thanks in part to Prometheus Records’ release of four of his best scores, he is happily enjoying some long-overdue recognition as a composer by fans of film music.

Ken and I met face-to-face on June 14, 1994 at the Amblin Entertainment office he shares with long-time friend John Williams. After graciously treating me to a delightful meal off the Universal lot, we returned to begin our talk. I was instantly struck by two things. First, there was an intense personal satisfaction with the path of his career. Despite a resume chocked full of well-crafted scores, he never had the opportunity to establish himself as a composer in demand. Even today, he still works hard as one of Hollywood’s pre-eminent music editors, most recently on “I Love Trouble” and “Robert Heinlein’s The Puppet Masters”. The second impression was a high level of respect for many of the composers he has worked with. Before beginning our interview, he was particularly intent on playing me some of Michael Convertino’s wonderful music from “Aspen Extreme”, a picture he had edited.

I was determined to focus only on his work as a film composer, since most of his press had leaned towards a career as “John Williams’ Music Editor” (the two friends had once joked that John should be called “Ken Wannberg’s Composer”). However, as our talk progressed, I found that it was difficult to separate the two as his experiences as both composer and editor were what made the man. Unlike some other composers that I’ve interviewed, there was no bitterness in lost opportunities, no attempts to create a superior persona. Ken Wannberg, pure and simply, had no regrets. He could look back and think his career nothing less than a success.

As with all things, we started at the beginning with his first exposure to music.

Did you come from a musical family?

No, not really, my family wasn’t musical, but I played by ear from the age of 5. I always wanted to play piano so I started to take lessons when I was 12.

How did you move from being a musician to working in film?

Well, I started in film after I got out of the service. I was playing in clubs, and I didn’t want to do that any more. A friend of mine on the west coast was a film editor and he said, “Why don’t you become a music editor?” I didn’t know what that was. He said they do the same thing I do, but with music. I said, That sounds interesting, so I wrote my résumé and sent it to the head of music at Fox, who was Ted Kane at that time. I was granted an interview, he liked me, and three months later I was hired. Not in music editing, but in copying. He said I should take the job, because if there’s an opening in editing, I’d have a better chance. So that’s how I got into music editing.

One of your earliest jobs was, I believe, on “Journey to the Center of the Earth”.

Ah, yes, with Bennie Herrmann. Frightful experience.

Was he everything that’s been said?

And more! But there was a charming side to Benny. He could be terrible one moment, and then turn around and be very nice. He always kept you off guard.

You were editing that film?

That was my first full-fledged picture as an editor. In those days you had an apprenticeship because the departments were big. I was an apprentice for a year and a half and then an assistant for a year. Some of the films I worked on as an assistant were “South Pacific” and “The King and I”. “Journey” was my first as a full-fledged editor, followed by “Hound Dog Man” starring Fabian. Remember Fabian?

Sadly. Now let’s clarify exactly what a music editor actually does. A film editor takes bits of a picture and strings them together, physically cutting the film. You’re not doing that with the score, are you?

Today, especially, you do cut the music afterwards, even if there are no changes. John will do a cut 12, 13, 14 times and out of those 14 takes he’ll take a little bit of one or the other. He’ll mark his sketch, which I go by, and then I’ll stitch it all together, so there’s a lot of cutting.

You mix together different takes?

Right. Whole recorded sections, several bars of music.

No sound re-mixing? A string section from this take, a horn section from another?

We record in a three-track configuration: left, center, right. Like you should record an orchestra. John doesn’t go in for all this tight pick-up where you have everything separate. A lot of composers will record on a 24-track and dub down later. John does it as we go along, so you balance the orchestra at the start and at the end of the day you have your mix. There’s no re-mixing afterwards. This is the way John has done it on all his pictures.

Have you worked in that fashion with other composers?

Yes. They, of course, didn’t have all the equipment back then that we have today.

How did you move from editing into scoring?

Being a musician and working in film, you make friends, and they would ask you, would you score my film? I think the first thing I ever did was called “The Game”. I used a six-piece orchestra made up with a harmonica, guitar, alto sax, piano, bass and harp. Or something like that! So that’s how I started. I knew the mechanics of it, and the mathematics of how to do it.

You’ve scored quite a few pictures over the years, more than many others who have been more actively pursuing a career as a composer…

Full-time composers?

Yes. You’ve also had quite a bit of variety, too. Gangsters, mysteries, sci-fi… Was this your choice to do such a wide range?

These were the pictures that came my way. Being in film, being behind the scenes, you absorb all that you’re exposed to, like a sponge. I’ve worked on several pictures with Jerry Goldsmith, John and several other composers, so you absorb all these different types of music. I’ve always loved film music, even before I became a music editor. I’ve always remembered the names of Alfred Newman, Hugo Friedhofer, and their like, and have been pretty awed by them. It just happens! You just go in and if you’re any kind of musician, you can switch from a love theme to a horror motif. Music is music. You should be able to do it all, and most composers can. Producers don’t seem to think that, so they type-cast composers. A composer does a light-hearted comedy that’s a big hit and suddenly that’s all he’s known for.

Elmer Bernstein was a classic example. In the mid-1980s, after “Airplane” and “Animal House”, he was the comedy composer. They forgot “The Magnificent Seven”.

And we know what he can do, too! Hollywood is a strange animal. Most composers are flexible, they can do anything, maybe they’re better at one style than another, but they can do it all.

On “Mother Lode” you used ethnic instruments like the bagpipe…

That’s a synth.

Really? And on “Philadelphia Experiment” you used more electronics?

Not a lot.

The bagpipe sound and the synths in “Philadelphia” each represented something that was either part, or outside of the human experience. Do you always try and latch onto something in each film that will reflect some major undercurrent?

A motif! Sure. To me that’s the basis of film music. Keeping that musical thread throughout the movie from the beginning to the end. Once you’ve got that, I think you’ve got the whole movie. People like John and Jerry are masters at it. They can take a four note motif and turn it upside down and do it all different kinds of ways. Maybe the audience doesn’t consciously realize it, but subconsciously it’s there. I don’t think it’s done today by a lot of young film composers. They don’t really know how to do it like the old time composers.

You feel music has not changed for the better then?

I don’t think so, no. Not from what I’ve heard. I think the real art of film scoring is a lost thing or becoming that way. There are people today who can do it, don’t get me wrong.

Do you think the fault lies with the composers or the demands placed on them by the producers/directors?

I think it’s ultimately the composer. When you go off and write, you don’t have the filmmaker there. You do what you have to do.

We are seeing a lot of scores being thrown out these days. Scores by people known for writing good music…

That’s true.

John Scott told me that he was able to write a really good score for “King Kong Lives” because he got a great brief from director John Guillermin. He was told exactly what Guillermin wanted before he started to write. Some directors simply tell the composers to go off and write, only to complain later that the score wasn’t what they had in mind.

That’s true and probably the composer will have ignored the directions of the director.

You do temp tracks as a music editor. Historically, they have become known as the composer’s worst enemy. When you’re laying a temp track, do you worry that it might force the composer in the wrong direction?

You do what you think is right for the film. I’ll use what is proper. It probably won’t be that composer’s music and it’s hard to do that anyway. To do a really good temp job you should try and glom on to one or two good scores that have the style that’s appropriate and try to treat it like a real film score. You can’t play those games, ‘Is Jerry gonna like this, Is John gonna like that?’ I mean, you’re out there alone, they’re not even around. You’re in a room by yourself, working from 9 o’clock to midnight, trying to get your end ready in five days so they can dub it in three days! It’s every man for himself! You do the best you can.

Is temp tracking a standard part of the music editor’s job?

It is now. It always has been, but not to the degree it is today. Now it’s a big thing. I was on “I Love Trouble” from December to June, just working on the temp. That’s a long time.

How was it to be on the other end, when you were composing and having someone else do the editing and temp track?

Well, when I did “Tribute”, the Jack Lemmon picture, there was a piece of music in there, alto sax solo, piano… It was good. The director, Bob Clark, said, “I don’t care what you do, you’ll never top what’s in there now. I love that piece of music and I want that piece of music. So, I want you to know that whatever you do, it cannot top that.” That’s a great thing to say to somebody, isn’t it? We had a little problem at the beginning, but he finally apologized to me after the score was done because he really liked what I had done. That happens. It’s part of the business, I guess.

When you’re wearing your composer hat, do you find yourself standing over the musk editor, trying to do his job too?

Not at all, no. On some pictures, though, I have done both jobs.

During our interview, we were interrupted several times by business calls reminding us that he still had work to do, finishing the temp track on “I Love Trouble”, and starting on “Robert Heinlein’s The Puppet Masters” for Walt Disney, which would be recording in England.

As we wound up our meeting, we chatted informally about his plans to retire someday and settle down to a peaceful retirement in England, a country he and his wife Elizabeth fell in love with on earlier visits. I could only think that Hollywood would soon lose one of its gentleman champions of quality film music.