Ottman enjoys experimenting, but they have to be carefully prepared rather than incidental. He wants to know his schedule well ahead of time so he can prepare as much of the score himself without ghostwriters. He has respect for classic film scores and their use of themes, and wants to keep that tradition going.

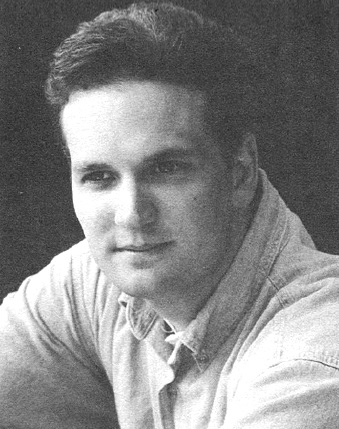

John Ottman is an anomaly amongst a business of anomalies: a film editor who became a film composer. His background as a filmmaker, as well as his astounding knowledge of film music history, gives him a perspective that few other composers can boast – and it shows. John acted in both roles on the recent box-office hit “The Usual Suspects”, and his score is both musically captivating and perfectly suited for the visuals. John lives tucked away in an unobtrusive but elegant apartment in West Hollywood, where, if you crane your head out the window, you can just see the billboard ad for “The Usual Suspects” peeking over the buildings on Sunset Blvd…

Tell us a little about your background… (“who is this guy? People wanna know…”) both musically, and how you came into film scoring.

I began playing clarinet in grade school, only because, like most kids, I resisted piano lessons. But that was about the extent of my ‘musicality’. Playing an instrument and being in band was always secondary to my desire to create radio plays on cassette, and also write and direct lavish super-8 film productions, often with big sets constructed in my parents’ garage. Instead of editing the films to music, I would extensively edit film scores to the picture. So, in a sense, I was “scoring” my films with music by Goldsmith, Williams, Horner and so on, much the same way music editors temp-score features. This “scoring” phase of my films was the part I looked forward to the most, and was often the very reason I was making the films. I could pretend the likes of John Williams were scoring my movies.

To make a long story short, I ended up going to USC film school where I was recognized for my [sic] for editing and directing. In my second year I was asked by a graduate student to re-edit his problem-plagued thesis project. It was on that film I bet Bryan Singer, who was a production assistant. After extensive reconstructive surgery on the film’s story, it ended up winning the student Academy Award for that year. So I became this “editor” in demand, yet it wasn’t really my career goal. Editing had always been second nature to me, considering the plethora of films I made as a kid through college. Upon graduating, I soon realized that with every project I did, it was film music that was the impetus behind my work. So, as a hobby I built a make-shift studio in my house with used MIDI equipment and began re-scoring my friends’ horribly-scored student films as an experiment, just to see if I could actually do this. Not being classically trained, yet having melodies and musical concepts in my head, the miracle of MIDI technology allowed me to perform these with synth, and create orchestral sounding music by carefully building and shaping tracks. My first film was “The Burrito from Hell”, which I did in a ‘50s monster movie style. I had such a blast that soon I was scoring short films and industrials like Ampco Parking and Kwikset Locks, as a hobby and training. At the same time I continued editing for people, including Bryan Singer’s short, “Lion’s Den”. He wasn’t convinced of my scoring abilities at that time, since all he had heard were cues from ridiculous little projects. But then on “Public Access”, his first feature, we lost the composer on the film, and the score had to be done in less than three weeks. There I was, the guy who had labored blood, sweat, and tears – for a couple months, the guy who lived and breathed this thing. I was drooling to score it, and I knew what I wanted to do ever since I began putting it together. So he gave me a try. And thus our editing/composing system was born. The film really was a showcase for me because many sequences were purely an interplay of wild editing techniques and music.

How did you score the film?

I had no computer at the time, just a little Roland MC300 sequencer. Thank God I had just bought a couple Proteus sound modulus for a short film I scored just prior to “Public Access”. They, along with my D70 keyboard – and a lot of tracks – gave us a pretty convincing sound. I wanted to open the film’s theme with a solo guitar, but the synth guitar sounded like a harpsichord; so the recording engineer would set the controls, run into the studio and re-play my synth guitar part with his own guitar, which really made the rest of the score very convincing.

Have you worked primarily for Bryan since that point?

I re-scored a John Wayne classic called “McLintock!”, which was a very strange project indeed. Apparently, the company re-releasing the film for video couldn’t get the rights to Frank DeVol’s music, so they looked for someone who could deliver the big sound of a symphony for dirt cheap. Moi. I had to do an hour and ten minutes of music, including all source cues, in less than three weeks – that seems to be the amount of time I keep getting. The funny part about the story is that because the old score was married to all the film’s production and dialogue tracks, the entire film had to be re-dubbed with other actors and all the sound completely re-created. A lot to go through simply to replace the score. I also did a ‘heartfelt’ kind of score for a documentary about autism, a Nike spot, and a few other short subject films. The frustration was creating all that music – which I poured myself into – only for it never to be heard by many people. It just sits on a shelf in my studio.

“Public Access” wasn’t released.

Strangely enough, no. But I’m hoping that if “The Usual Suspects” is successful enough, that interest in “Public Access” will heighten enough for a limited run. It was quite a good film, very disturbing, dark, and twisted. It had a real intelligence and showed an incredible amount of resourcefulness on such a low budget. Overseas, one critic referred to it as the best American film of the year, which I thought was a perfect quote to use on a video box. But it didn’t even get that far. I hope it’s because the distribution company is holding out for a theatrical run.

On Bryan’s films you serve as both editor and composer. How do the two roles interact?

Bryan’s films have always been a sort of study of the characters, very introspective, often backdropped in some strange world. Given that, I would hate to be the composer brought in cold to score such projects. By being so involved emotionally as the editor and creating these characters over a period of weeks or months, it is easier for me to be more insightful with the score, versus superficial. The benefit is a better though-out score emerging from within the film, as opposed to covering over the surface. There’s not a night during the editing process that I don’t toss and turn in a swirl of musical idea – ideas that I can do nothing about until the scoring begins. It’s very frustrating. So once the scoring process starts, I’m like a race horse out of the gate.

Do you actually start to develop the thematic material while editing?

Not normally. Not immediately. Once I’ve been editing for a month and a half or so, I start getting an idea of the score’s tone. But physically it’s impossible to begin writing any musical themes. We have never had the luxury of relaxed editing schedules because the budgets of out films have demanded that we cram five months of editing into three. I was basically editing 13-hour days, seven days a week. Once in a while I managed to squeeze in some studio time and start experimenting with themes. I think my theme to “The Usual Suspects” went through four versions before I was ready to have Bryan hear it. But there were a couple of instances where I knew conceptually how the score needed to be as I was constructing a sequence.

There’s one scene in the film where a 747 lands [‘New York’s Finest’ on the CD]. Simply having it land would be so typical, so I jump-cut it, giving a very strange feel to the scene. But I knew these jump-cuts would have to work with the score – my hits on the music would have to be exact. So this was one of the few instances where I used a click track to make sure my editorial timing were on beat.

How would you describe the stylistic approach you chose? It seemed to be a combination of several different elements.

Maybe, but I think it’s all within a pretty traditional orchestral context, despite some strange techniques I used. My main approach was to ensure that this film had class and richness. The expectations of a film entitled “The Usual Suspects” is that a more hip, contemporary score would be the thing to do. But Bryan and I both saw eye to eye that this was a film about dispelling expectations, and from the moment the theme begins, the audience is immediately keyed in that this is going to be something they didn’t expect.

Also, Bryan, Chris (the writer), and I deeply respect and make the filmmaking style and quality of films of the ’60s, ’70s, and early ’80s. Some of our favorite films stemmed from this time, as well as some of the most brilliant scores – real scores. Consequently, “The Usual Suspects” is a sort of homage to scores of recent days gone by. The films of that time were generally better written and better developed than most of today’s. That, coupled with the fact that composers were given more time to write, created more coherent and more fully developed scores.

Who in particular are your super-heroes from that period?

Goldsmith. Some newcomers to this man’s work might scoff at my worship of him because he’s done so many poor films in the last ten years or so. But to really know Goldsmith’s repertoire is to be astounded. My assistant is only 21, so I forced him to listen to scores like “Alien” and “Masada”, etc. He was mesmerized by them and their detail and their freshness. It’s a style and detailed quality of music that is not as pervasive today. I love so many other composers too, from Barry to Bernstein, each offering something very unique to the field.

Were there surprises at the scoring session?

I was prepared for a train wreck at every turn, but things couldn’t have gone smoother. I guess the biggest surprise was how good everything sounded, and at the same time, how close the orchestra sounded to my synthed versions. The Proteus instruments sound so good, that they gave me a very comfortable feel for how it would sound for real.

One problem we had, however, was the fact that the studio we used had a little Yahama piano, which is what I walked over immediately to start playing the film’s theme – a theme basically driven by piano. One hit on a key and I knew I was in trouble. The theme needed to sound elegant, and this thing sounded too bright. So we scrambled to try and find a larger piano. We were in San Diego, so it wasn’t easy. Finally we found a company that could deliver a Steinway for a day. We had been behind recording other instruments on our piano day, and it had to go the next morning. At about midnight, after having gotten through the opening and ending titles, our pianist had to go, so my assistant took over and we laid down piano until six the next morning. He did great, but occasionally, out of fatigue, he would flub up here and there; but we just pressed on and buried any errors in the mix.

Given that you’re taking this big step into the large-scale film scoring world, what kind of projects would you like to score stylistically?

I would love to do a “Dances with Wolves” kind of score – sweeping vistas, emotional themes, etc. At the same time, I have a comfort and excitement doing big action music or dark, creepy stuff – all within an intelligent orchestral context. I would also love to do some epic – or a big science fiction film. I am blessed to have had “The Usual Suspects” be my first big score because of the variety of styles within this one piece of work – thus it’s a good calling card for me.

I’m kind of curious. You mentioned to me that there were some weird instrumental effects thrown in now and then, like the guiro I think. Were these off-the-cuff experimentations or…?

Never. Never. Perhaps if the studio time was free and we had a relaxed schedule to keep, but in a frenzy, everything’s got to be thought-out and prepared ahead of time. Besides, I’m way too paranoid to depend upon what I might come up with fooling around in the studio. I would definitely like to do that when I can; however, in this score, there could be no errors. Every single sound layer and every percussive instrument was completely calculated. That goes for the guiro, for example [in the cue ‘The Garage’]; yet it was still exciting to hear how great it sounded for real. By the way, in that same cue, if you listen carefully, you will hear light strumming of piano wires. These were the fingers of Bryan Singer at two in the morning.

When you’re writing stuff in your studio, do you just sequence it in as you see the picture?

Well, God knows if I have been the editor, I’ve seen the film about a million times by the time I’m ready to score it. I can recite the dialogue in my sleep. If I haven’t edited the film, I watch it a couple of times and sleep on it. I then go at it by watching each scene that I feel should be scored, and then preparing these scenes for scoring. I first decide a general tempo, then extensively “catalog” each action or event by marking what measure or beat it occurs. After that, I basically turn the video off and write the cue based upon my notes and general memory of the scene. I get through the whole scene, creating a sort of awful sounding skeleton of the cue. I’ll then interlock it with the video again, and see how I did. If everything hits and the flow is working, I’ll turn off the video again, and orchestrate like hell – which is actually my favorite part of the process. To me, this is the most crucial phase because what bells and whistles and textures I add is my personality or style as a composer. I couldn’t conceive of handing a bare skeleton of a cue over to an orchestrator to completely anticipate my concept for the scene. A talented orchestrator is great for filling in any areas I may have neglected, like more bottom-end here, fleshing out brass lines, doubling things with a few other instruments there, adding some interesting accompaniment, and so on. After a while, he’ll be able to understand how I think musically, and take liberties with the music, which I welcome. It’s my worst fear, however, that there will be some project where I have to write two hours of music in some ridiculous time frame and I’m forced to dole out my work to an armada of orchestrators just to get it done. I hope I can avoid such nightmarish scenarios. We’ll see...

Is your interface just yourself on the keyboard? Do you sequence in real time, or do you edit statically after that?

I’m all alone in that little room. But I’m Mr. Butterfingers on the keyboard (should have taken those piano lessons), so, yeah, I’ll go in there and edit notes with the mouse. But most of the time, I’d rather slow the tempo down and perform the cue so that my notes are more on the bears in order to avoid having to go in and edit all my mistakes later. For very fast things like glisses and what I call “string swirls” (like in the cue “Getting Aboard”), I’ll just butterfinger them. For the director, this “mess” can be worrisome, so I describe what it will sound like, or strum my fingers across the keyboard to give him an idea. I say, “trust me.” Then I go to bed worried, hoping the hell it will sound like the way I described!

So your musical background is formally just lessons in high school. You seem to have intuitively grasped the art of film music writing.

I guess most of my music education came from attending performances of my favorite works, and that’s how I learned a lot about orchestration. I would go to the symphony in my home town (San Jose) looking wide-eyed at the ensemble the whole time. After hearing a work, say Dvorak’s 9th, for years and then finally seeing it performed I was witnessing how textures were created. When I began writing film scores, I would actually take out my Music: An Appreciation book and open it to the page which showed the layout of the orchestra, keeping the scenario in mind as I wrote. So I may have been in front of an electronic keyboard, but in my mind, I was sitting in the middle of an ensemble. I guess I still put myself in that sort of mental state when writing now. The other way I learned was simply to fill my head with oodles of film scores. In fact, scores and classical music is about all I listen to, which is an advantage and hindrance at the same time. The advantage is that when I see a raw scene in a film, my mental catalog of film and classical music immediately gives me an idea of what I need to do. The drawback, I guess, is when I’m sitting in the car with one of my friends and there’s some song playing on the radio or a CD, I have no idea what it is. And perhaps I shouldn’t admit this, but I feel the original “Star Trek” series was responsible for a lot. It not only got me interested in science fiction, which then led me into the film world via “Star Wars”, but the “Star Trek” series showed how the same music could be adapted and extensively edited and re-organized to score a myriad of different scenarios. It was great music, some of its uses is quite dated and overly dramatic today, but it was great stuff. You rarely hear that sort of compositional effort and care in today’s television series.

In the future do you see yourself more as a film editor or film composer?

Film editing will always be in my blood, but film composing is my real passion – and I think I have a knack for it as well because of how closely I have tied it to the editing in all of my projects. I’m getting offers to edit major pictures, and I’m saying no to them. That’s scary, but I don’t want to be considered an editor who dabbles in film music; rather, I want to be considered a film composer who happens to be a good editor. With Bryan Singer’s films, you’ll always see me dong both, because he won’t let me score unless I edit, and I won’t edit unless I can score. I think the outcome is something rather unique, so we both see the merit in it. My only concern is that editing keeps me out of the scoring loop for a few months, and I might miss projects I would love to score. That’s frustrating, but I also value my unique dual role on Singer projects.

Do you write independent pieces of music separate from film?

I used to write suites and pieces of music just for kicks and to explore certain musical styles, but I don’t seem to have the time for that lately. But part of the advantage of having done larger, yet unknown projects such as “McLintock!” Is that they served not only as devices for me to prospect new writing techniques, but they were also guinea pigs in terms of showing myself how much music I can write in a certain amount of time. So when I was faced with three weeks to write the score to “The Usual Suspects” I knew I could pull it off because I had written an hour and ten minutes for “McLintock!” in that same amount of time. It seems I am haunted by this three-week thing. That’s all I had for “Public Access” as well. Anything less would be inhuman, yet I know it happens. I just don’t want to hear about it because it scares the hell out of me. Sometimes the film music process seems to resemble a meat factory where scores are churned out like hot dogs. Yet the music is often a film’s last great hope of bettering itself.

You seem to do a lot of things compositionally that other composers seem to grow into, such as re-using themes in different ways to heighten continuity.

Well, it’s what traditional film scores have always done. In the last 25 years or so we’ve toned down the overtness of just how these recurring themes are used, yet to me, this concept is the cornerstone of a good score. I have a real reverence for what to me are the “real film scores” because of their careful attention to character and motifs. I guess I’m in that kind of mind-set because that’s the kind of score that turns me on. Not that today’s film scores don’t employ this technique, yet many seem to have stayed, using looser motifs and less precise concepts to carry the score. And of course, it certainly depends upon the film. Overall I would say that films of the last ten years or so lack the story integrity that films had, and the score is often affected by this in terms of its own development. Sometimes the films don’t warrant such a traditional approach, and the music serves less as a story-telling element and more as an overriding atmosphere. Yet I have seen many films which, in my opinion, would have benefited by stronger narrative-style scores as opposed to this new-age, atmospheric sort of Tangerine Dream approach. In terms of character themes, “The Usual Suspects” was tough for me because it’s a film about events and five characters whose actions and fate are all controlled by one man, Keyser Söze. Therefore, thematically I used one main theme and altered it for the major characters, and the actions in which they partake. In fact, if you listen to some of the action-oriented music, such as “New York’s Finest,” it’s really the film’s main theme twisted around; after all, it is Keyser who is pulling all of their strings. Of course, there were secondary motifs introduced as well, like the “heist music” and “Kobayashi,” a mysterious theme when Keyser is talked about, and then just straight, fun action stuff not rooted to any theme at all, except its own. But I tried to remain as traditional in my approach as possible within a very bizarre film structure.

How much synth did you use in the score to “The Usual Suspects”?

Not much, really. Finally I got to do a score where I could use more orchestra than synth! We didn’t have the time and resources to incorporate a couple strange percussive instruments, so I had to replace them with sampled versions, and there and there I brought in some strange textural sounds to add an edge of eeriness. I think many composers, like Goldsmith, have shown that synth is a legitimate section of the orchestra, yet sometimes I feel guilty simply turning to synth to make things otherworldly or strange. Before the advent of synth technology, scores like “Planet of the Apes” used incredibly strange textures by pushing the envelope with acoustic instruments. That takes a vast knowledge of the unconventional things instruments can do, but it’s something I would like to learn. I’ll feel more proud of my work if I can do that.

So do you think you’ll get to the point where it’s all acoustic?

Depends upon the film. If I were doing “Black Beauty”, of course. But I don’t know. I go see a film like “The Shawshank Redemption”, which is basically orchestral, yet way in the background some electronic pads are integrated within the strings to add a strange quality the orchestra could never emulate. I respect that a great deal, and it drives me nuts because I want to know what sound the composer is using. Where did he get that?! I want it! Thus, I went out and bought a bunch of equipment to try and create my own, but sometimes creating those textures electronically can be as time-consuming as researching how the orchestra could do it. So, to answer your question, unless it’s a period piece, my scores will always have some sort of electronics lurking somewhere.

Talking about how being the editor gives you an additional edge to working on a project, do you find it easier to work with the director and producers?

Well, the editor is a very intimate and integral part of the film who has given birth to this thing after having nurtured it for months. So naturally, there’s a real trust factor going on that may not be there if I were some composer coming in from the outside. When you’ve worked on creating something for so long, it becomes a real mission to ensure that this film’s music is going to be the best it can be – to bring out every moment and nuance we created in the film. Our reputations are on the line, and we’ve invested so much time in it, none of us want it to be in vain. And talking about exposing oneself to criticism, I’m under twice the pressure to make sure the film is working well on both an editorial and musical level, or else my name is Mud. I’m not really thinking about that when I’m on the project, but when we’re done, I worry that editors won’t take me seriously as an editor because I did the score, and more worrisome, that composers won’t take me seriously as a composer because I edited the film. However, to my delight, I’ve had nothing but support from both sides. So perhaps there’s hope that I won’t be an outcast after all. Basically, I think every film composer would love to be involved in the editing, and most editors involved in the scoring. But practically speaking, especially considering the fanatically squeezed post-production schedules, this is usually impossible.

The drawback of editing for me is the fact that I’m out of the loop for a couple months. If the film has a big budget, the editing process could last for months; therefore I will only be editing Singer films. The result of having edited the film, of course, is a better score for me to put out there, but there will be less of them.

My pitch is that I come to a project with the mind of a filmmaker. Not that other composers don’t – I think the best composers are essentially good filmmakers – but because I came from a filmmaking background I come to a film with perhaps a little different sensibility. I see my score as simply another illusion of filmmaking like editing, lighting, sets, etc. Therefore, I have no qualms about recording a score in an unconventional way – as long as the final recording sounds good and works for the film. A score can be an illusion just like everything else in a film.

So what’s down the pike?

Knock on wood, if all goes according to plan, I’ll be scoring at least one segment of a Miramax science fiction anthology film called “Lightyears”. The story I know I will be doing will be directed by Bryan, so, of course, that means I’ll be editing. His segment is called “The Last Question,” based upon an Issac Asimov story concerning the end of the universe. It’s executive produced by Michael Phillips, who produced “Close Encounters of the Third Kind”, and you know who scored that. Shakin’ in my boots. After that, Bryan’s got a film in the works based upon a Stephen King story. So there’s stuff ahead, but I would like to try and score a project between Singer films. I love working with Bryan, and always will, but, you know, I’ve got to break the umbilical cord at some point!

So “The Last Question”, dealing with the end of the universe, will warrant a large group?

We’re talking about the end of everything. Gigantic. Choral music, brass. Holst-city. But you’d be amazed how you have to convince them that a big score is warranted! The original music budget was $30,000. That was so outlandish I simply laughed. Since then we have tripled it, but we’re still going to have to make it sound bigger than it really is, which I’m used to.

Do you find any other areas of media scoring to be of interest?

Nothing will compare to scoring a film, but I did dabble in scoring a CD-ROM project called (are you ready for this?) “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream”. I was hired because the company wanted someone who thought like a film composer to score the project as if it were a film. There were five characters, each having to have three themes each. When all was said and done it was over an hour of music. It was less pleasure than a film, and it was fun, but the drawbacks are that all that music will never be heard on any CD, and the music you will hear has now been “computerized” to emulate through people’s PC sound emulators. Yuck.

Have you ever had to deal with another composer on a project on which you were a filmmaker?

On smaller films I did at USC, and it was either a pleasurable experience where I learned a lot about scoring from the composer, or a very frustrating experience. It depended upon the composer, and I guess, how well we agreed or worked together.

You’ve also done a lot of larger scope student films at USC… “Alive and Kicking”?

I decided that since I want to score big films, I would do “big” student projects. “Alive and Kicking” was a kind of military-style, wacky score, much like 1941. It was a blast to do very serious, aggressive military music for this comedy, much in the way Elmer Bernstein seriously scored “Airplane!” for comedic effect. One thing about student films is that no one may ever hear your work, but you create a little library of music for yourself that perhaps one day you can draw from for inspiration. I have written a couple other themes to no particular film at all that I’m dying to use some day.

But you write every theme specially for the movie on the spot, of course.

Of course. But there are these couple themes I’ve written that need to find a film.

You seem to have defined for yourself a musical style. Do you think Bryan’s films elicit that style?

To a point, certainly. His movies, so far, have been pseudo-art films that delve deeply into character. We had to find a way to make these films more accessible to the audience, and the score played a large role in that. The score’s role is to bring a little Hollywood to the films; the end result is a film which is a sort of amalgam of Hollywood and art. That’s a real strength behind our films, I think. That’s why Bryan gives me great latitude in the editing room to try and milk scenes dramatically and create huge musical sequences to keep the film engaging for all.

Is it to parallel that kind of mixture in your scoring?

Absolutely. The fringe benefit of this kind of approach to filmmaking and scoring is that the score can’t be too Hollywood, because nonetheless, it’s still an artistic and intelligent film. So as a result of working on a Singer film, the music ends up sounding more suave, refined. It keeps me in check from doing something too flashy, or corny, yet it has to be bold… It’s a fine line I balance all the time.

How did you work with the music editor in terms of how the temp score was designed?

I didn’t want a music editor. My editor was brought on after the scoring session. So it was me and my soundtrack collection that temp-scored the movie. The producers were insistent I hire an editor to do it, but I knew what the color and style needed to be. So I gave it a try. Bryan, whose first feature I also temp-scored, and then ended up scoring, endorsed my doing it. The irony is that my own temp score often came back to haunt me in terms of Bryan falling in love with many cues. But, at least I agreed with his passion, since I had chosen the music.

How do you feel the music sounds in the final mix? Were you involved in that?

I’m very fortunate that the score is very featured in the film. Films today seem to be going sound effects crazy, when it’s often the case that the music is the element that should be carrying the scenes for the film’s cohesiveness. Once again, films just 15 years ago knew the strength of this. I mean, look at the big chase scene in “Outland”. Music is featured, effects are supportive. And it worked marvelously. Because Bryan, Chris, and I all revere films of that era, we held true to them all the way through to the mix. Of course, having the music mixed too loud in a scene can be equally frustrating and embarrassing, if it is meant to be subtle. There were a couple areas where I would have liked the music to be a tad higher, but I can’t complain about a very good mix. There were some scenes that were completely constructed for score, like when the camera dollies away from the porthole – an extremely dynamic scenes. All effects were dropped, and it’s just score. (As the editor, I made sure that would happen!)

I was very involved in the mix; being the editor helps add legitimacy to my being at the mix as a composer. As long as I could convince them that I was there as the editor and not so much the composer wanting the music blasting in every scene, I had a lot of creative input. I was really expecting the mix to be a bloodbath, but it really went incredibly well.

Did you have any experience with an orchestra prior to “The Usual Suspects”?

I had a little experience with some library music I wrote for a company down in San Diego. The main composer of the company’s music, Larry Groupe, heard my demo tape, which included my score from “Public Access”. He asked me if I was interested in writing a cue, and knowing it would be with real players, I jumped at the chance. The problem was that I didn’t even have a computer. So this project gave me the impetus to get set up with Performer (my music writing software). Technically, I stumbled along the way, but with manuals in hand, and some help from Larry, it all worked out. His motive was that perhaps one day I would get a film and hire him as my orchestrator and/or conductor. It was great a couple of years later to be able to give him a call and say, “Well, here we go.”

How old are you?

Well I’m not 26, like James Horner was when he did “Battle Beyond the Stars”! And I’m not 30, which is what he was when he did “Brainstorm” with the London Symphony. I’m 31. Sigh. But we finished the film a year ago, so I can say I was 30. Okay, I feel better now.