Larson asked these questions by mail. Miyagawa discusses his involvement in the "Yamato" series. He explains how the composer must make up for anime's limited animation with vivid themes, which are written as stock music for the editors to pick through. He wishes that music was given more thought by the producers of Japanese animation.

Music for American animated films has largely been cartoon music, that is, wall-to-wall melodies closely synchronized to the often frantic on-screen visual action – a technique which has been called mickey-mousing due to its Disneyesque origins. However, as animated feature films became more sophisticated and dealt with less cartoon-oriented subjects, scoring often mirrored the style in which non-animated dramatic films were scored. Animated pictures like Ralph Bakshi’s “Lord of the Rings”, “Watership Down”, “The Plague Dogs”, and “The Secret of NIMH” all featured dynamic and moving orchestral scores which belied their animated origins and gave them the same sense of drama and excitement as live action films.

Japanese animation (called “anime”) has followed the same suit. When anime really took off with films like “Space Cruiser Yamato” (1977, derived from 1974 TV series), they emphasized a strong use of music as a foreground element of the film. Music wasn’t simply relegated to the background, but was a large part of the picture – and an equally large part of its commercial spin-offs, as witnessed by the plethora of anime soundtrack albums released in Japan.

Music for anime usually draws from a mixture of classically-oriented symphonic music and popular music, characterized sometimes by the lyrically melodic orchestral scoring of Joe Hisaishi’s “Arion” (1985) or the heavy metal rock and roll of "Odin" (1984) – although more often it’s something in-between, capturing and emerging the flavor of both worlds of music.

Hiroshi Miyagawa’s music for “Space Cruiser Yamato”, from its initial television series through its four feature films, characterizes this approach. The music is dominated by a lovely melodic main theme, usually heard from wordless female voice, which contrasts with themes for other characters that comprise pop tunes and jazz styles, all of which capture an evocative musical texture which contributes greatly to the ambience of the films.

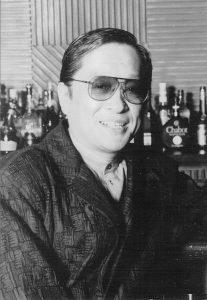

Born in Hokkaido in 1931, Hiroshi Miyagawa received his education at the Kyoto Art University and the Osaka University. His first music job came in 1950, as a night club piano player. In 1955 he moved to Tokyo and became a member of the Seiji Hiroaka Quintet, moving to a band called “Six Joes” four years later. In 1961, Miyagawa began to arrange and compose music for radio and television, eventually going on to score more than twenty motion pictures. During the 1960’s he won several awards. During the 1970’s he composed, arranged, and performed for many stage shows, TV programs and movies, and during the 1980’s his work expanded to other areas, including a disc jockey for radio, a book and magazine writer, host for a TV movie show, and guest on quiz and talk shows. Miyagawa was also featured in his own show, playing at popular theaters and hotels. He is respected in Japan for his film score “Yakusoku” (“Promise”), although he is most popular – and best-known abroad – for his music for the anime series, “Space Cruiser Yamato”. The “Yamato” movies (which were released in somewhat different form in the US under the Saturday morning cartoonshow name, “Starblazers”) resulted in three separate TV series and a TV-movie from 1974 through 1980, and four motion pictures from 1977 through 1980 – at the initial height of the original anime Golden Age when it first invaded the USA. Miyagawa is also credited with writing the song that appears in the 1964 Toho classic, “Ghidorah, the 3-Headed Monster” (scored by Akira Ifukube). In addition to the “Yamato” scores, Miyagawa also scored such anime films as “Grand Prix Hawk” (1978, TV series), and “Maaterlinck’s Bluebird” (1980).

How did you receive your first assignment to compose music for a motion picture?

Mr. Hachidai Nakamura, the composer of “Sukiyaki”, was scheduled to compose for a rock singer movie. When he became ill, I was asked to take his place by Watanabe Productions, whose president was also the leader of the popular band, Six Joes, of which I was a member at that time.

Coming from a background in popular music, how did you approach writing the score? What challenges did you have in composing to specific situations and timings?

I did not give it much thought. As I watched the film, I wrote battle music for battle scenes, sad music for sad scenes, according to the director’s orders, fitting the music into the specified time required for each scene.

What do you see as the purpose of film music?

I think there are several, but since movies are a collective art form, I think: there is the rather obvious purpose of using the music, as one element along with the visual image, to make the work appeal to an audience.

What is your personal approach to scoring movies?

I listen to the views of the director, other executives, and peers toward movie music. I simply believe that it’s good if the movie can be made better by my music.

What types of films did you score when you first started composing for motion pictures in the 1960s?

There were a lot of comedies such as 日本一の無責任男 (“Japan’s Most Irresponsible Man”), and 日本一のゴマすり男 (“Japan’s Worst Flatterer”) from the series starring Hitoshi Ieki, the singer/actor of the Japanese comic band, “Crazy Cats”. I also wrote the music for “pop song movies” (movies that star a singer who has a hit song). There was 会いたくて 会いたくて (“I Wanted to See You So Much”) and 夢わ夜比較 (“Dreams Open at Night”) which starred a singer called Marl Sana.

How did you get the assignment to score the “Space Cruiser Yamato” television series?

It began a number of years before “Yamato”, when the producer made an animated television program called “Wansa-Kun” and put me in charge of the music. “Wansa-Kun” was a story about a little dog by the same name and it had about 10 minutes of musical sequences in every episode. For Japan at that time, when money was not spent on music, an unusually large amount of money was spent on music for this delightful musical animation.

What differences did you find in scoring an animated film after having done live-action movies? What special challenges did they give you as a composer?

The biggest challenge is that the number of themes (the number of characters) is high, and the amount of time that music is played is more than double that of ordinary movies. In a silent movie where no one is speaking, there are some scenes that are more effective without music. But in the case of animation, that kind of scene has a completely still screen – that is, there is only one picture which becomes a situation without any flavor or spice. So a lot of music needs to be put in. The pay in Japan is too low and it’s a hassle.

The “Space Cruiser Yamato” score seems to derive its style from both classical and popular musical traditions. Would you describe how you integrated these two styles into your music for the “Yamato” films?

I’m not very familiar with the classical style, so I’ve written mostly in the popular style. There are some tunes which I wrote in the popular music idiom, with a classical flavor to them. Scene by scene, depending on who the main character is, I’ve used a classical-like style, such as a kind of baroque music or an imitation of contemporary music like Stravinsky’s.

In composing your music for the “Yamato” television series, did you write new music for each episode, or did you just write enough music to cover various situations which were then edited into the soundtrack as needed?

In the case of television, due to various circumstances such as budget, I’m told to make the music all at once. With “Yamato”, for instance, I composed several types of violent battle scenes, several types of ‘tension music’ that precede a battle, and also several tunes using just the melody of the Yamato theme – transposing it to sound more classical for scenes with a psychological climax, and transposed into a sad tune for scenes of a lover’s or a friend’s death. In this way, I imagined various scenes from the beginning and composed hundreds of cues. These were stocked up and the sound effects director chose cues to match the story and set the music to fit the scenes. Then the producer approved it and he or someone else put the music into the movie. In short, I wrote several hundred cues that made up the original music, but I had nothing to do with the decision of how to use that music by matching it with the screen.

Did you find it invaluable to start the series at such an early stage, or would you have preferred to score specific sequences after they were filmed?

In the case of “Yamato”, the producer was extremely enthusiastic toward the music, so at the point that the concept was almost complete, he told me to make a number of general movie songs, saying he wanted to put out the record first to promote the film. At this stage, the storyline had only just been written. He just described the visual imagery to me. He asked me to make several dozen songs from which he would select only a few, so this job really took a lot of time and energy to compose. I had a lot of trouble. It was really very tiring. After editing, though, I was asked to compose for specific details. I also composed new songs, and there were a lot of additions.

How closely did you work with the director and the animators? Did they give you any specific suggestions for musical style or its placement?

The producer for the most part assumed the position of animation director, dubbing voice specialist and musical director all by himself, so, being a one-man show, most of the suggestions were his. Thus, I didn’t have a very close relationship with other members of the crew. This way of making a film was extremely unusual, I think, but since it became a hit, I’ve had the experience of having to listen all the more to what the producer says!

How large of an orchestra was used for the first “Yamato” television series?

There were two or three trumpets, two trombones, one each of flute, oboe and clarinet, two horns, about fourteen strings, and one each of piano, bass drum, guitar, Latin percussion, and classical percussion. For just a regular show band I think, it was an extravagant ensemble. It wasn’t such a grand orchestra, there were maybe 30 musicians.

Was your music for the “Yamato” feature films taken only from the music you wrote for the TV series, or did you compose new music or new themes especially for the movie series?

For the very first one (“Space Cruiser Yamato”, 1978), 24 of the 30-minute television episodes were chopped up and edited into a two-hour movie. The next one, さらば宇宙戦艦ヤマト (“Arrivederci Yamato”, 1978) was a movie especially made for the theater, and for that one I composed new music.

Did the success of the first “Yamato” movie help you as a film composer?

No, that’s not the case. You might think that as a result of the success of the first movie, my solid position as an animated movie music composer would be established, but that has not been the case at all. Since then, there hasn’t been any great increase in the number of job offers for movies or animations.

Were you involved in all the different music albums of “Yamato”? Why were there so many other versions by other people – Chorus Suite, Piano Rhapsody, Romantic Violin Yamato, Synthesizer Fantasy, Disco Version, etc.? Do you think these re-arranged versions detract from your original recording or orchestration?

Yes, I was involved. The Chorus Suite album was different; but I transposed and recorded the albums that featured piano and violin, the disco version and most of the others. Since I arranged them myself, they don’t really detract anything.

Were you given bigger orchestras or bigger budgets, or more time, for the later “Yamato” movies?

The organization grew gradually and the orchestration became more symphonic. What was about 30 people in the beginning grew to 40 or 50 players. The number of strings and brass nearly doubled, and the sound became extremely rich. I felt that the music as a while sounded very heavy. It became extravagant, but on the other hand I felt that it became too much like classical music. But then in order to express the feeling of that massive battleship Yamato, you needed to do it with an orchestra this rich.

Please tell me about your score for the film “Maaterlinck’s Bluebird”. I have heard that this film was scored in the manner of 1940’s American musicals!

For “Bluebird” I didn’t especially try to compose in the manner of a musical, it’s just that from the various styles of music, I like songs from musicals that I’m familiar with. So naturally my music tends to resemble that. I had no particular intention of writing with the musicals in mind.

You also scored the animated TV series, “Grand Prix Hawk”. What type of music did this particular series need?

This wasn’t so different from “Yamato”. I was even told sarcastically by the producer, “What is this? You’ve used the same music as “Yamato”, haven’t you?” That’s because my music has a distinct flavor to begin with, so that after hearing it once, there is a quality that anybody can tell it’s the music of Hiroshi Miyagawa. It just happened that I used this trait in “Yamato”. In other movies, there are cases where it is used and cases where it isn’t. I didn’t use any special methods for “Grand Prix Hawk”.

What are the conditions in Japan for composing and recording your music for a movie?

The way money is spent varies greatly between the scope of the movie and how big a budget the film company has. Also, the producer’s point of view, the director’s point of view and others are each different, so a matching budget and a matching orchestra are used

Will you be scoring any more animated films in the future? What other projects do you have underway?

I’d like to score more animation, but these kinds of jobs go more often to young musicians. I feel very sorry that the experienced musicians like us are considered to be old-fashioned. If the heart and essence of movies and music are deeply understood, and the skills of composition and transposition are completely mastered, then regardless of age or approach, music that satisfies the listener can be written. The executives for movie music and television in Japan are prone to be taken by what is novel, unconventional, and shocking, and they too often chase after passing trends. I wish they would settle down and endeavor to produce more lasting music.