LoDuca discusses how he met Sam Raimi and came to work with him on "The Evil Dead". Raimi and LoDuca alike wanted to play the score straight even while the film was a comedy. He makes an interesting observation about his own accidental "craft" in writing three-note motifs for a movie about three generations of women. LoDuca is based in Michigan and he talks about the difficulties of making himself seen by the LA crowd.

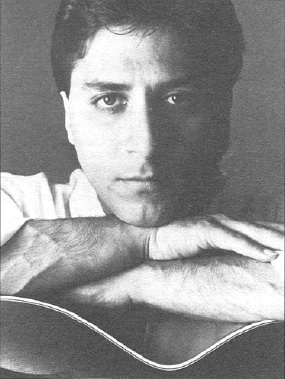

Horror fans would be the first to recognize Joe LoDuca’s name in the opening credits of one of his projects. Coming from a jazz background, the composer began his film scoring career on Sam Raimi’s 1982 horror cult classic “The Evil Dead”, from which stemmed work on a number of genre films, including Raimi’s super-offbeat “Crimewave” (1985), the superior 1987 sequel “Evil Dead 2”, “Moontrap” (1989, starring Bruce Campbell and a non-Chekov Walter Koenig), Necronomicon (1993), and the third “Evil Dead” film, “Army of Darkness” (1993). What will surprise many is that LoDuca has also been involved with a number of non-genre TV movies (most recently “Fighting for My Daughter”, an ABC telefilm that ran in early January) and made-for-cable specials HBO’s “Comedy Jam”), in addition to being an award-winning composer of TV/radio commercials. He’s worked for Jeep/Eagle, Bell Atlantic, Kmart, Lincoln/Mercury and others, winning eight Emmys in the process. He continues to base himself in his home state of Michigan and is current working on the Universal syndicated TV series “The Adventures of Hercules”, executive-produced by Sam Raimi and Rovert Tapert. Joe and I talked on December 20, 1994, and I would like to thank him for taking time out of the Christmas rush to discuss his diverse projects. Varèse Sarabande hopes to release an album of “Hercules” music sometime in 1995.

My first question is the standard “how did you become involved in film scoring,” and how your musical upbringing played a part in the beginning of your composing career…

It just so happens that the first score I ever did was for Sam Raimi, and it was “The Evil Dead”. I had been pursuing life as a young musician in New York for a while, kind of living to play my two gigs a month in a Greenwich Village jazz club. I was also studying privately with teachers at universities in Manhattan. I moved back to Michigan and was just beginning to concertize other classical guitarists, and I had also gotten some grants from the Arts Council of Michigan to composer. In addition, I was producing demos for a female vocalist, and the man who was producing the vocalist was involved in filmmaking. From very early on, he was involved with Sam and Rob [Tapert, Sam Raimi’s friend and producing colleague] in helping to put some money together for an independent horror feature called “The Evil Dead”.

So, we were all eventually introduced, and the reason we were introduced was because the producer had previously told me, “You know, Joe, you’re really good at this music thing. What do you want to do when you grow up?” Never having really thought of it before, I said, “I think I’d be pretty good at writing music for film,” and that casual remark ended up changing my life. I was introduced to Sam and Rob, and I really got a kick out of scoring “The Evil Dead”. I wasn’t necessarily a horror film buff at all, but in the horror genre, the music is contemporary, and can be as wild and crazy as you want it to be.

So it was a really crude effort on all of our parts, but it kind of worked! I had five out-of-tune string players, one of the first synthesizers, a percussionist friend bang on some stuff, and we just made a film score.

I was about to ask what the recording conditions were in scoring the original “Evil Dead”…

Well, we recorded it in a little attic studio, and we literally had five string players, and kind of had this gnarly string quartet sound that was supplemented by some synth and a lot of percussion that I played, as well as prepared piano and very early synthesizer things – basically just anything that we could get our hands on to make scary noises.

Later, when I saw the music on the screen, I said to myself, “I like this, and I really like doing this.” So, even though I continued to perform and have a jazz band for quite a few years after that, it just sort of happened that I was having a much easier time getting these type of [film] commissions than trying to be the leader of a jazz band going broke. The very first piece I wrote for television was a piece for a talk show; it was the first thing I had done and it won two Emmys.

So the handwriting was on the wall that this was something I wanted to look more into. But, I have continued to live in Michigan, even though, at this point, I suppose I’m technically bi-coastal for the amount of time I spend out there. However, my residence and family is here.

What has been your relationship working with Sam Raimi, Rob Tapert, and Bruce Campbell on the “Evil Dead” films?

What’s great about it is that we all came up together. Success hasn’t changed or spoiled them, and they’re just as enthusiastic as they used to be. They’re maybe a little wiser about how the business end of it works, but they’re still like big kids in a candy store – they love [making films], and so it’s great being around them.

Sam just has this wild visual sense – these amazing images he gets on film. Bruce has incredible energy and stamina like no one I’ve ever seen. Rob keeps a million things going at once in the same direction, and it’s impressive.

When making the original “Evil Dead”, did you ever think that this project was going to lead to something bigger down the road for you and everyone else making it?

I enjoyed doing it, and I enjoyed the people I was working with, but I never in a million years thought of what would happen next. From what I gather, the film cost very little to make, and it made $40 million worldwide…

Did that surprising financial success happen instantaneously?

The fact that it became a cult hit, and was recognized as being something original – even in a low-budget kind of way – did happen nearly immediately. The fact that it was picked up overseas and did well took a little while to build up steam. You know, the Science Fiction channel showed it on Halloween, and the film was made in 1982, so I guess it has some sort of staying power also, for those who follow the genre.

On the third “Evil Dead” film, “Army of Darkness”, extensive re-editing and re-shooting took place, and your “Time Traveler” cue from the original conclusion was removed from the finished product, which featured an entirely new ending. [Note; That track is included on Varèse’s soundtrack album, and the original ending – with ash sleeping too long and waking up in a post-apocalyptic future – is included on the Towa Video Japanese import laserdisc, curiously retitled “Captain Supermarket: Evil Dead III”.] I was curious as to your thoughts on the refilmed ending.

I think the idea was for the film to end on a lighter note, have you leave the theater smiling.

The classic, “Hail to the king, baby,” line…

It’s the perfect way to end it.

Do you think there’ll be another one?

Oh gosh, I don’t know. I’d say “never say never.” It’s all in the mind of Sam and Ivan [Raimi, Sam’s brother and co-scripter of “Army of Darkness”].

Danny Elfman wrote the ‘March of the Dead’ theme for the film [recorded with the Seattle Symphony; LoDuca’s music was recorded in Utah, contrary to the album credits]. I was curious as to how that situation worked.

You know, I really don’t know, but I think he was put in before I was on the picture. I don’t know, [but] it makes for a great montage.

It seemed to at least work extremely well with your score and fit perfectly with the film.

Yeah. You know, it was not hard to figure out. We were in epic territory, on well-trodden ground, so we might as well have fun doing it. For me, the choir was a kick, [using] members of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir. My favorite piece is the anthem for the Army of Darkness, ‘God Save Us’. So it was fun, because we also had all the other wacky themes – the jigs, the comedy scenes, the ’50s sci-fi nod from the “Klaatu barada Nikto” representation in the script.

The one thing that Sam and I have always agreed upon, even in higher powers had not, was that the score is dead serious. If you want to crack a joke, that’s great, but the score should always be serious. The bigger and more serious the music is, the more entertaining the film becomes.

What is your whole scoring process like?

I try to stick with that, and then, of course, see what the director has in mind since it’s his story and his point-of-view. At that point, I assess where the important musical revelations are in the story, and try to attack those head-on, be it in the form of important scenes or particular themes. Then, it’s up to the subconscious to take over and put it all together.

This latest TV film [“Fighting for My Daughter”, which aired on ABC January 9th] was real interesting in that I transported a whole recording studio to Los Angeles, and was away from all sorts of normal influences since the buttons were all in a different place. So, I had to develop a different technique just to get the sounds. This film is about three generations of women, and I found out, about three-quarters of the way through the score, that I was writing every cue in three, and I was using a three-note motif for the whole thing. It was real interesting to see the multiples of three occurring throughout the score, and to watch it happen.

Fangoria magazine named you Composer of the Year this past year. You have done a number of diverse projects, but do you ever worry about being typecast as strictly a horror composer?

Well, “Hercules” is big and epic, but it’s not horror. It’s adventure and action, and he goes to worlds that never existed. This allows me one week to use Armenian music, the next week it’s Japanese, and all kinds of interesting ethnic drumming in between.

What has been nice about the TV scores I’ve done is that they’ve all been contemporary, not horror films. I’ve done a thriller, an action-adventure on the Rio Grande, and “Fighting for My Daughter” is a real edgy contemporary score with a lot of interesting source music – grunge, techno, rave - that we actually produced as well. It’s not a genre story at all.

One of the reasons why I decided to stay and have a base in Michigan is because, when I decide to retire from performing, there’s a huge advertising market here with the big three auto companies and all, and I’ve done very well writing commercials. It’s really great. Today, I was in Chicago and I did an a capella men’s gospel thing for a spot on NBA rookie Grant Hill. I used a young 12 year-old singer of Stevie Wonder-quality who just knocked my socks off.

So, for those folks who only follow my film projects – and it’s admittedly very hard following commercial composers – I’ve done every kind of music imaginable, and it’s been really great that way. My diet has been quite varied, it’s just that when I’ve been called to the orchestral arena, it’s often been to do big horror scores. So I don’t really feel like I’ve been running anything into the ground.

When I heard that “Hercules” was coming back to TV, I immediately thought of those Steve Reeves things I’d watch on a local UHF station’s “Creature-Double Feature” Saturday matinee. I was surprised at how the creators of this version found a tone that’s straight but not too serious, campy but not overtly ridiculous. What have your impressions been about the program?

First of all, I like the program a lot. I think for what they’re producing on a TV budget, the production value is nothing short of amazing, and they do it by shooting in New Zealand, integrating live-action models with CI effects, getting quite a value for the dollar for the sets.

Of course, New Zealand looks beautiful, but what it has to do with Hercules and Green mythology is virtually nothing! [laughs] But it doesn’t really matter – this is, for all practical purposes, “Star Trek”. You have stories that have a moral and a theme, and also the big action and fantasy aspects for those that crave that end of it. You also have a very likable Herc who women love. The demographic was supposed to be 11-14 year-olds, but you’d be surprised at who’s actually watching this show. I think it’s pretty unique, since it doesn’t look like anything out there, and it’s certainly tremendous fun for me.

It’s a big, full orchestral score, unlike most television efforts that use drab electronics. How was the decision reached to provide a full orchestral sound on a TV program?

The orchestral experience that’s happened with “Hercules” is unheard of in having a large orchestra for television in this day and age. One of the ways we’ve accomplished it is by creating a library that gets re-used. Rather than doing all the score with a medium or small orchestra like on the old “Star Trek” fight scenes where you’d say “I think that was a French horn there all by itself,” we go for the bang-for-the-buck approach by writing less music that can be incorporated into a library. One sea monster one week is as good as the next’s… that was the way I had to devise a plan for using large orchestra and get support for doing it. So we have chorus and full orchestra, all on a syndicated television show.

How have you adjusted your time-frame to fit the confines of a television program?

It’s a TV schedule, so it’s very fast and loose. Getting cues to the dub mix has been quite a challenge. At first, I was doing it with overnight mail, and lately the schedule has been so tight that we’ve been sending them digitally down the phone lines to get them there.

Has technology advanced to the point that working in Michigan is not a handicap for you?

It’s very, very hard to develop the pursuit of being an A-list composer being in a place like Michigan, although there are some A-list composers who live in New York, which is in the same time zone, for all practical purposes.

So… I’m holding out. I think it’s a matter of developing quality relationships with people who really trust you, your instincts, and your communications together. Once that’s established, it really doesn’t matter where you write. It really doesn’t. On “Army of Darkness”, I’d write a cue and call Sam up and say, “here, this is what it’s gonna sound like,” or send it over on a videotape when there’s that sort of time. I think that on that film I did mock-ups of everything, so that there were really no surprises on the scoring stage.

So, it can be done by traveling, it can be done by commuting – it’s just a question of meeting interesting people to work with, and developing a rapport with them. I’ve met a lot of them right here in Michigan.

Looking at all of your projects and achievements, you’ve been involved with several different forms of music and media. What has been the most fulfilling aspect of your musical career?

I guess it would be to work with people who trust your instincts enough to really let you go out on a limb and see what you bring back. Very often when you have that kind of support, what you bring back is very gratifying. If you write music, there’s nothing more exciting than going crazy for three weeks and writing music for orchestra, and then getting it played back in your face… after all that revving up of the turbine engine, getting that creative flow going, having 70 or 80 guys playing your music, there’s nothing like it in the world. After a while making music with synthesizers gets a little tedious. Music is intended to be made with people for people.