Article on Michael Kamen's diverse film work, from action to romance.

First thing in the morning, Michael Kamen picks up the phone at the plush Encino recording studio/ residence that he co-owns with Dave Stewart and other busy composers who use it on a time-share basis. Luciano Pavarotti is calling from Rome. He wants a special arrangement of ‘Have You Ever Loved a Woman?’, the Bryan Adams hit that Kamen co-wrote for the movie “Don Juan De Marco.” Kamen will conduct Pavarotti in a concert for Bosnian relief in Italy in September, and Luciano is in love with the song, singing it over the phone.

The mailman arrives with, among other things, a tape from new-age harpist Andreas Vollenweider; it’s a collection of new recordings that he wants Kamen to listen to, knowing that the composer uses the top soloists from around the world for his film score orchestrations.

By mid-day, Kamen is up the hill, past the tennis court, in the studio that Stewart built and where such bands as the Eurythmics and the Traveling Wilburys have recorded hits. David Sanborn, David Letterman’s favorite sideman, is sorting through a dozen reeds for his clarinet. “They used to last two or three months,” Sanborn says. “Now they die in two or three days. The cane is not so good.”

On three video screens set above a huge recording-engineer’s soundboard, Cindy Crawford is spread-eagled on the hood of a truck inside a box-car. Billy Baldwin stands between her legs, his pants around his knees. In the darkness an armed bad guy stalks them with a night-beam. It’s a scene from their upcoming Joel Silver thriller, “Fair Game,” for which Kamen was writing the music.

Sanborn, Kamen and his engineers are more interested in how Cindy’s theme, which the clarinetist created, blends with Billy’s theme and the bad guy’s music, which Kamen composed, and how they all intersect on each beat of the sequence.

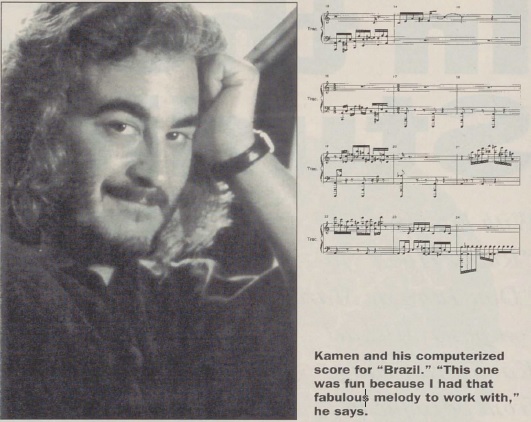

Behind them, on a Macintosh computer, on a program called Performa, all the notes heard over the Cindy and Billy encounter dance magically on a music score come to life. Chords, clefs and quavers zip along on a series of charts as the recorded music they represent echoes through the studio.

As it turned out, Kamen’s computer is where that music would remain. When the shooting of “Fair Game” was delayed into September, he was forced to give up the assignment to focus on another Joel Silver project, Richard Donner’s “Assassins,” starring Sylvester Stallone. “This shit happens all the time,” says Kamen. “I’m always making music. Sometimes schedules clash and sometimes I have a theme a director doesn’t like. But it’s never wasted.”

On that July day in Encino, while Sanborn (whose music will probably still be heard in “Fair Game”) was revising Cindy’s theme, Kamen strolled down to a small studio in the residential area. There, another imposing Kurzweill, Kamen’s synthesizer of choice, sits next to another Macintosh and a video screen.

Kamen hits some buttons and moves the computer mouse about. Stallone comes on the video screen looking as wounded a soul as ever Bergman dreamed of; escorting a soon- to-be-dead bad guy to a lonely rain-covered field photographed by Oscar-winning camera man Vilmos Zsigmond.

Over the studio speakers comes Kamen’s haunting theme, a melody for oboe written and played by the composer that echoes the weary pain in Stallone’s eyes. Even the notes on the Macintosh look forlorn.

“Sly told me he was tired of the music always going boom in his movies,” Kamen says. “He’s aware that the music in his pictures usually expresses his maniacal wildness, that guy. He wanted a theme with a sax but I said we do that in ‘Lethal Weapon.’ I said, why not go more classical. How about an oboe? And he loved it. Mind you, Dick Donner hasn’t heard it yet.”

But Kamen and Donner go back a long way, through all the “Lethal Weapon” pictures, and the director knows that Kamen was an oboist at Juilliard and that his unforgettable melodies have enhanced pictures from “Brazil” to “Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves” to “Don Juan De Marco.”

How can Kamen go from Cindy Crawford’s sex-and-chase action to Stallone’s melancholy drama in the time it took to walk down the hill?

“I’m reactive emotionally,” Kamen says. “Up there, I react to that. Down here, I react to this. You trust your instincts. I’m not over confident; latent artistic insecurities always surface. It’s reliance on expression and a proclivity for melodic music.”

Kamen sits down at the Kurzweill and looks out the window and an original melody comes out of his fingers to be captured by the computer. Hand on mouse, he watches the notes move and listens closely as his music plays. Stopping, he zeroes in on a misplaced note and with a click of the mouse corrects it. When the theme is replayed, it’s flawless. Someday it may show up in a movie, either as a plaintive solo or with the huge orchestration that Kamen sometimes revels in.

“I never trained in orchestration. I’m a rock-and-roller,” Kamen says. “When I went into rock-and-roll, my classical friends no doubt thought it was for the money. But I thank my lucky stars I wasn’t trained in the classical position to have only weighty ideas. I want to express myself musically. I’m very well versed in music from many countries and many eras. There are no restrictions. My hands can wrap themselves around a romantic concept or a baroque concept; everything from baroque to the blues.”

Much of that stems from his New York City upbringing when his parents exposed him to everything from Bach to Gilbert and Sullivan. Pete Seeger and Leadbelly were family friends and he began playing the piano, guitar, clarinet and oboe at a very young age. He draws on all those influences for his work.

To write a movie score, Kamen likes to watch as much of the film as is available. “You poke through the film and get an idea of what the nature of the music should be,” he says. “Then you deal with what the specifics are, and what the effect of the music should be.”

For “Assassins,” Kamen started with Stallone’s character. “He’s a man in pain; it’s such an introspective role for him and he’s magnificent,” Kamen says. “In the front of the movie, I’m left-footing you with the music, trying to make you nervous, trying to make the theme stick to Sly. For five minutes, he doesn’t say a word. When he does, it’s just two words and his face is filled with pain. The oboe comes in and it’s the first sign of his character.”

he romantic fantasy “Don Juan De Marco” was another story. “In ‘Don Juan,’ the effect was to get you to sing,” Kamen says. “To get you involved in the romance.”

Kamen is as proud of his music for “Don Juan” as anything he’s ever written. He had established a relationship with Canadian rock star Bryan Adams and record producer Robert John “Mutt” Laing when they collaborated on the soundtrack for Kevin Costner’s “Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves.” Kamen wrote the music with Adams and Laing providing the lyrics for the hit song from that picture, “Everything I Do (I Do It For You),” which sold six million copies.

“I had the theme for ‘Robin Hood’ in my brain for 25 years but didn’t have a use for it until then,” Kamen says.

By the time “Don Juan” came along, Kamen, Adams and Laing had become great friends. “It was the three of us working together,” says the composer. “Bryan is brilliant and Robert is the greatest rock producer ever.” (Laing has produced everyone from AC/DC to Def Leppard to Michael Bolton to his currently chart-topping wife, Shania Twain.)

Back in the studio at the top of the hill, not knowing that Kamen’s music would never be heard in “Fair Game,” David Sanborn is indicating a little trill in the score that accompanies the bad guys.

“Don’t worry,” says Kamen, “since they’re Russians, we’ll get one of the top balalaika guys to do that.”

That’s how he thinks, and he’s passed it on to Bryan Adams. The way Kamen tells it, for ‘Have You Ever Loved a Woman?’, Adams wanted a top flamenco guitar player to accompany him. Kamen suggested Paco de Lucia. Adams, who was recording the song in Jamaica, called Paco in Spain only to be told that the maestro was going on vacation and regretted that he would be unable to play.

“Couple days later,” says Kamen, “Bryan was walking on the beach, looked up and spotted Paco. He hadn’t mentioned that he was vacationing in Jamaica!”

The flamenco legend immediately agreed to join Adams in the studio on the island.

“Tapping all the emotional resources in a melody, that was Bach’s goal,” Kamen says. “He could see it almost in an architectural way, the way a theme could spread itself around. It was the affect of the music. All of us should try to live up to that tradition. We owe that tradition to live up to it.”