In this enormous interview, he discusses his belief in music as a communicative medium; he says that beginners often have more to say than experienced intellectuals. He discusses the travails of working with inexperienced directors ("Don Juan"), difficult deadlines ("Robin Hood") and poor-quality films ("Die Hard 2"). This is conversational and he discusses his perspectives on the movie business, and the difficulties and rewards of working on large productions.

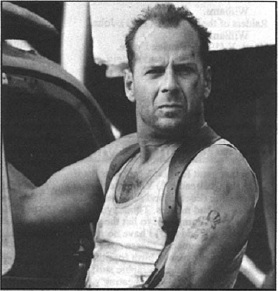

I had heard that Michael Kamen was a personable guy, one that I could perhaps feel comfortable joking around with. So when I arrived at his studios, I mentioned his recent birthday, two days earlier or so, and said, jokingly, “How’s it feel to be the big six-oh?” (meaning 60) and did not expect the kidney punch that followed (He actually only turned 47). Crouched on the ground in agony, I realized my fallacy, you don’t fuck with Micael Kamen. I mean just his name along incites intimidation. This man is John McClane. But seriously though, arriving unexpected at the Encino studio he was using (some miscommunication or somethin’) I was a bit anxious about the man who often had to battle terrorists, psychic mayhem, and a corrupt future society; also a man behind some rather dope ass-crunchin’ music. But upon meeting him, I was instantly put at east. The man glowed. He actually began changing a cue at one point for his latest picture, “Die Hard 3”. (He was actually in the process of recording the score up in Seattle. The date: April 17th; the film’s release date: May 19th, a week or more left. Yikes.) He was figuring it out on a keyboard, whereupon I suggested he should perhaps do it in the style of The Firm (i.e. solo piano). He chuckled at this and then punched me in the kidney. We passed by an orchestrator or someone and he told him to use the Styrofoam cup. I asked what he meant and he said that it makes a great sound when you run a bow over it. He mentioned how he was upset about his deteriorating piano skills, and made a few other interesting comments before we could find a bloody suitable room in his lovely adjacent home to turn on the bloody tape recorder. Nonetheless, I managed to get an hour and a half on tape, and was still aching for more by the end (didn’t yawn once). Knowing already that he was one hell of a talent, it was nice to find out he was also one hell of a guy.

[Into the tape recorder] He says he can’t play for crap anymore so just put that in there, Will.

[Laughs] I can play great oboe, I can player very good Bach on the piano, but my improvisation is not what it used to be.

There you go, that’s word for word. So, uh, Pink Floyd, you played with them?

Yeah, I played with them, I co-produced one of their albums.

But you didn’t actually play…

I’m not a full-fledged member of Pink Floyd but last year at this time I was in LA, so were they, they were playing the, what’s that called, the Rose Bowl?

Yeah.

They’re good friends, and it was my birthday, and I said, “You know what, instead of having dinner at the house tonight, let’s go to the Rose Bowl and I’ll play oboe with Pink Floyd. So I took my oboe down there and played oboe with ‘em.

[I laugh] That’s… spontaneous.

Yeah. [snickers] Rock and roll should be fun. That was my first impression when I was at Juilliard. When I was at Juilliard I formed a rock and roll band and I used to like playing sort of what would pass for serious contemporary 20th century music at the time, but mostly because it was a joke. It was fun to improvise freely and get 500 kids in the park and just point at them and get them to do something. And that was spontaneous and that was kind of imaginative. It was incredibly sophomoric, we got a lot of pleasure out of it, and then we discovered that grown men were getting grants and Pulitzer prizes for the same rubbish.

i.e.?

i.e. look at the list of Pulitzer prize winners for that. [we laugh] Modern, serious music has become embroiled in an intellectual discussion that has no place in music. Certainly, the great composers of the past were geniuses and used their intellect, but only to serve their emotions and guide their craft. Not to dictate to them what they should or shouldn’t write. Rock and roll seemed to offer at that time, the late ‘60s, a great field of expression, being able to play my own music, to play with other people, to play for crowds and have them be responsive. It was that direct relationship with a really responsive audience that spurred me on.

The urge to perform…

Not so much the urge to perform but the urge to be responded to. I love music in any form, shape, or direction but it’s a communicating art. It’s about communicating emotions and if you’re doing it in a blank room late at night, it’s not as much fun as getting feedback and seeing human beings react to what occurs to you. The goal is to respond to your inner voice, not to the applause of the audience, that’s not enough. If you’re only in it for applause, that won’t sustain you past the age of 26.

So you’re saying ideally you’d like to be in a room writing but your instincts are to perform and be inspired by that?

I think I do have a performer’s instinct and I have a player’s instinct, so I like writing music for orchestrates that they enjoy playing. One of the first time I wrote an orchestral work was for a ballet company in New York. My overriding desire there was to play music that the dances wanted to dance to. I’ve been really lucky in being able to exercise that.

I guess that comes from the experience of being a performer.

From being a performer, yeah, because I certainly wasn’t trained as a composer, or as an arranger or a conductor or orchestrator. None of that stuff was part of my education. I was trained as an oboe player from the start.

You started in Juilliard, is that right? Your evolution…

Well, my evolution started when I was two years old and was very imitative of the wonderful music my parents played in the house. They played such a great variety of music, they played a lot of Bach, and they played a lot of Gilbert and Sullivan, they played a lot of Leadbelly and Pete Seeger and it all was one very friendly area for me. I never drew distinctions between Leadbelly and Bessie Smith and Back and Handel, and I got a great deal of pleasure out of all of it equally.

You often reference it in your material. It’s not like a blatant steal. You’re paying homage to that stuff. It’s obvious you appreciate it.

Thank you. That’s all I can say to that. [laughs] No. Stravinsky actually said good composers borrow, great composers steal.

Right. [laughs] No, I mean it’s not like, it’s something you state. Even in Don Juan, there’s a moment where it’s just obvious and the audience knows it, they’ve heard it. But you’re not claiming it’s your music, you’re saying, “this is fun.”

“This is derived from and it certainly is fun.” And I love, you know, working on a piece of music, only to find that I’m reinventing a piece that existed 200 years ago. So finally I’ll cop to it and say, “Yes, this is where I’m coming from.” “Die Hard” is filled with those references.

Yeah. Talk about that. Beethoven’s 9th, was that just…?

When we first spotted “Die Hard I”, and I had no relationship with the director didn’t know him, went into see the film and we spoke about it, it seemed like most action films feel when they’re not finished. ‘Cause they are a real collaborative art. They are a testimony to the collaboration of various crafts in Hollywood.

You mean specifically action movies.

More so than anything else because the level of acting is not what sustains them completely, the personalities on the screen certainly sustains them. The music is a personality, too. [At this point he gets a call from a maker of “Don Juan”, something about the album.]

I thought your music was excellent for “Don Juan”, by the way.

Thank you. It was an incredible struggle because the director was an amateur. He was also a genius, and it’s a curious combination of just enough knowledge to be extremely dangerous and not knowing the mechanics of the business but playing with the mechanics of the business. It turned out to be a real struggle with Jeremy Leven that at the end descended into one of the worst relationships I’ve ever had with a director.

Really?

Yeah, and this is a guy who I love and admire. There was a lot of love in the process of writing, but we just seemed constantly to run up against each other?

What was his incompetency, I mean…?

Never directed a film before. I mean, I love my daughter but I wouldn’t ask her to fix my car.

Right, but did he have instincts as far as…?

Yeah, yeah, many, many instincts but he didn’t have the experience to let people who knew what they were doing guide him. He was convinced he was in control… I think it’s the classic director’s problem, that they wind up… I mean, when I produce a record I wind of producing not only the record but my children’s lives, dinner for the next door neighbor, you just get into a head of “I’m the one who’s responsible for this, I better come up with an answer for everybody’s problem.” Directors can be forgiven for feeling that way.

It takes two to tango.

Yeah. [snickers] The good news is I’m out of my twitching phase and able to look on the film, very gratified with the score.

It seemed like you’d have fun writing something like that.

I did have fun writing it. I had to convince him on an intellectual level of every note. Because he’s a psychologist.

He just couldn’t make decisions.

He made decisions. I don’t want to get in… it isn’t a fruitful area for discussion because the good news is I’m out of it. The music stands for itself and Bob Shaye who runs the film company is an old friend, and it was nice to redirect my efforts at a film that I really did love and believed in. I was totally seduced by Johnny Depp. I believe that character. I too was Don Juan. It was like doing “Robin Hood” where I felt I was Robin Hood. I don’t know who that guy in the tights was but I was Robin Hood. [I laugh]

You probably could’ve done the accent better.

Yeah. [chuckles]

Well, the good stands, you have the music…

Well I’m very, very, very pleased with that score and it was, uh…

They are doing an album, right?

Yeah, the album’s out this week, that’s what we were just talking about.

Oh, okay, great, I’ll snag that.

It all comes out weeks after the film.

Sometimes years…

Yeah, if at all. The “Brazil” album didn’t come out for eight years. [chuckles]

Did you used to be fatter?

Yeah.

[I laugh at my bluntless] I mean, I remember the hair, I remember the beard. I just remember a different look.

No, I was heavier.

You look damn good.

Well, thank you. In print. [I laugh] I lost about 25 pounds last year. I decided I was growing up and it was time to shed that puppy fat.

And stop growing out.

Yeah. I always used to remember people saying, oh you’ll outgrow it, and I kept waiting for the time to come and I said, I think it’s time.

Well, let’s go back to “Die Hard”. You’ve done three of them. Have you seen an evolution? The third seems to stand out, I’m psyched as hell to see it. But it seems a little different. Is there an evolution to it? Do you feel satisfied with the music’s evolution? Stop me when I make sense.

Well, films like “Die Hard” are pure entertainment. There isn’t a subplot behind the story that’s going to inform anybody about the quality of life. There are built into the film certain witticisms. [His wife enters ushering in their old Labrador] Out, out, out…

Wife: Can you keep him for a minute? This man doesn’t like dogs.

That’s all right. [She leaves] He’ll fart in your face. He once farted right in the face of a director.

[laughs] Really?

“Die Hard 1” was about this phenomenal bad guy, Alan Rickman. It was peripherally about John McClane in a bunch of air conditioning ducts. [I laugh] But his character pursued and beat the bad guy and the mechanism involved in that makes everybody cheer. If the bad guy’s bad enough – I mean, Alan Rickman was as bad as you get. He was a delicious bad guy. He had such personality, so many funny lines and such a great attitude. You were really sorry for him to go because you knew that was the end of him.

“Die Hard 2” was not such a noble effort. It was made mostly to capitalize on “Die Hard 1”, with Renny Harlin instead of John McTiernan. The bad guy wasn’t particularly dignified. There was a lot of cool action. There was a lot of gut-wrenching tension, the kind of stuff you’d come to expect from a movie like “Die Hard”. I think “Die Hard 3” is a return to a very short path. John McTiernan is clearly the best action director in the world. He has that method down. He’s a rock and roller on the camera. We were talking about a shot he was making the other day where nobody would do it and they didn’t have the right mounts, so he mounted a camera on a tire and he rolled the tire, and got out of the way before the helicopter took his head off. He’s rock and roll, he really does shoot from the hip and he knows his business.

When we met for the first time in “Die Hard 1”, I at that time had done “Lethal Weapon” and a couple of action pictures, but nothing as big as “Die Hard”. And I wasn’t overly impressed with it, it didn’t have its special effects. There were a lot of scenes missing, a lot of dialogue missing and just thrills and spills missing, as they often are near the end. It was a good movie. I was growing to love the bad guy. When he said he had a notion to use Beethoven’s 9th for the bad guys, I was flabbergasted. I actually said to him, please, if you want me to fuck with some German composer, I’m very happy to take Wagner to pieces. I’ll do anything you like to Wagner but can’t we leave Beethoven alone? This is one of the greatest pieces of music celebrating the nobility of the human spirit of all time and you want me to aim it at a bunch of gangsters in an American commercial film. His answer was so cool that I had to go with it, and I’m paying the price ever since.

His answer was that he reckoned that his bad guys were the lineal descendants of the bad guys in “Clockwork Orange”, [I laugh] and they always listened to Ludwig van. It was such a cool rationalization – this was the fulfillment of their life’s dream, to walk into a room filled with gold and hear Beethoven’s 9th. For those of the film audience that don’t know Beethoven, I suppose the theme has its own power and majesty. For people who did know Beethoven, I think it was probably a great nod to the tongue in the great cheek which is what the film is about. It is a wonderful tongue-in-cheek adventure which you don’t really take seriously until the bomb’s about to go off or the plane’s about to crash, or something that you can’t help reacting to puts you on the edge of your seat and for some reason we call that fun, scaring the shit out of ourselves. [He laughs] But that’s what “Die Hard’s” all about. John McTiernan is back on “Die Hard 3”.

I think you like him.

Well I love him. Because he’s a very, very skilled director and he’s become a friend. We’ve worked together on a few productions. You really do respect the ability of a pro. When you’re dealing with a pro who’s got that much stuff that they have to hold together and they do it so admirably, you’re dealing with a master at their trade. It doesn’t matter if they’re Rembrandt or some chalk painter on the sidewalk in Venice, it’s going to be done brilliantly. I think he dignifies his movies with a great deal of skill and intellect and I’ll take care of the compassion. I wasn’t allowed to play with guns as a child, I wasn’t allowed to read comic books and now I score comic books made out of stories having to do with guns. I guess it’s a nice way to earn a living but it is not what I’m on the planet to do. I’m really to be able to do it.

“Die Hard 3”, because it’s John again, is going to be derived musically a great deal from “Die Hard 1”. I’ve had a couple of little musical conceits locked away for this one. I don’t get the same canvas that I had in “Die Hard 1” that gave me an excuse to have fun. In “Die Hard 1” it was Christmas. Since you had Beethoven’s 9th from “Clockwork Orange”, I insisted that they buy “Singin’ in the Rain” to keep it intact. So I had “Singin’ in the Rain,” which sounded very much like “Winter Wonderland,” which I also made them buy, and I very happily, sometimes wittily and sometimes stupidly combined Beethoven’s 9th with “Winter Wonderland” and “Singin’ in the Rain,” to such an extent that I barely invented a theme for the film itself. And thank God I’ve got like four notes I can stick on the movie that are reminiscent of “Die Hard” and what the theme is.

When I think of “Die Hard” the theme does come to mind.

[He hums the four notes] Not a hell of a theme. Nothing you could stake your life on but I have now milked it for three films.

So they never released the first album.

No. The first album was a mass of contractual union complications.

They came close. Fox was releasing a “Predator”/“Die Hard” combo.

Yeah, but they didn’t do it. The commerce of this business really drives the business. Truly and really the market for an action-adventure film is not gonna translate automatically to record stores. It might for “Don Juan”, it might for “Clockwork Orange” even. There are some movies that make you want to get the record. You want to hear that music to relive the experience. I don’t think people want to scare the shit out of themselves late at night by listening to the “Die Hard” record.

[laughs] I do.

Well, okay, I like that stuff too. I used to sit at the piano and improvise four second cues, imaginary cues for imaginary episodes of “Twilight Zone”. I used to scare the shit out of myself and that’s kinda where I started realizing the power of music and movie.

“Die Hard” for me was a huge surprise, I went into the theater and it just blew me away because I didn’t expect it. And a lot of it had to do with your music which always manages to capture a unique feeling. To listen to the album of “Die Hard” would be to recapture that feeling.

Well I hope you get something out of this album because the vicissitudes of commerce mean that I am now two weeks away from finishing recording the score although the film will be out in three and a half weeks and the record was done last week. So the record will be a compendium of cues that are done so far.

That happens a lot, huh?

I mean, I know I shouldn’t say this, but when I’m actually making it, I do really believe that the effect of that music is far more powerful than the movie itself. So…

Uh-oh.

It’s nice to hear music to a film like that isolated from a film, “Oh, that’s what was going on underneath that truck.”

The mixing on your movies is pretty poor, I think. You can barely… I mean, you can feel it, but it’s, like, bring it up.

Yeah, you can’t really hear it. I couldn’t agree more and that’s really a lament from being a rock and roller where all I wanted out of life was to play louder and louder. I always find that strange about films, that music is treated as part of the sound effects track, when it’s actually part of the dialogue. It was one of my big beefs about “Don Juan”. The music and the visuals could have made a beautiful film. The language of the film was beautiful but the director was so obsessed with hearing every molecule of people’s lips moving that he turned the music down. I suppose it has its effect but it’s not alive, it’s not vibrant, not sexy, it’s not what the movie is about.

Well, I guess if people end up commenting on the music then they may not have really been watching the movie.

Yeah. But my own parents can come out of a movie and say, “We didn’t actually notice the music,” and that’s saying something. No, that’s great. I am a collaborator up on screen. You’re not supposed to think about it until afterwards, saying, man, that guy was great, or that score was great, or that dialogue was great…

The end credits.

Yeah, some people stick around but like Bryan Adams said when we did the “Robin Hood” song – he said he finally went to see the film and when the song came on, it was just him and the cleaning lady in the theater. [I laugh] He said, “We both loved it.”

It was still a huge hit.

Yeah. Big hit.

“Lethal Weapon 3”, for instance, that subway chase on the album – it was awesome. I even used it in one of my little student films, it’s just so powerful. In the movies it’s like [make some attempt at subway sound]. I mean you can hear everything else, it’s frustrating.

Well thank you.

In “Lethal Weapon 2”, there are some action cues left off, I think.

You’ll have to come ‘round one day. We’ll give it to you. We have it near. I should get somebody else to make my soundtrack albums, because they are normally done in a mad panic – the last night of the dub and the record is due and there’s people waiting at the door for the tapes. The truth is, we have no idea what we are doing by the end of a movie. That’s what happens, and [whatever we come up with at the last minute] is what gets on the record. I know a state of oblivion is sometimes part of the nirvana in this business, but it doesn’t help to finish a movie score and then have to get back in the studio the same night and compile all the tapes for an album. You forget very quickly what you had. You put a cue in and it’s not in a related key to the piece that came before so you take it out. I’m missing whole big chunks of “Robin Hood”, and in “Don Juan”, some of my favorite cues aren’t on the record because they were done in such haste.

You don’t have much choice because you are the last step in the process in the film. It’s hard to blame you. It’s just frustrating for a fan. [laughs]

Sorry to disappoint you. When I make my own records I won’t include those actions cues. You know, early on when I first started writing for film I realized my love for Stravinsky would come in good stead, my love for Shostakovich would come in good stead, my Russian background would come in good stead. Now that I think, I do bring a lot of that stuff… it’s not my power, it’s the power of that music into my scores. I love big flashy orchestras because I come from an orchestra, I know what fun it is to play that music. I can’t describe how much fun it is to stand in front of an orchestra and have them play it for me.

How did you handle when you first started out when they maybe couldn’t afford such a huge orchestra, or was there ever a…?

Yeah, I didn’t know that that’s the way it went. My first film score involving an orchestra was a thing called “The Next Man” (1976). It was a Sean Connery film and it was being done in New York. I was used to making rock and roll records and in those days you did make an album in a weekend. In the studio with Pink Floyd on the second year of a project, I do reflect back on the days when it took a week. Recording that “Next Man” score, there was no money. I hired an orchestra mostly of friends in New York which meant it was a very fine orchestra indeed because I had luckily the best musicians in the world as friends. I had them in the studio and I was still writing the last dots on one of the cues and the copyist was waiting at the door anxiously because we had only a three hour session booked. I was saying, “Well, it’s three hours, the score’s only 45 minutes long, let’s go.” Today we can take three hours and not get two minutes of music done. There is that aura of specialization that hits film scores. It’s what we do for a living and we want to make sure it’s done as well as possible, but it is sometimes gilding the gilded lily to spend all that money on recording a film score that will be heard peripherally under a bunch of explosions. It’s a great extravagant waste of time.

On The Next Man I had actually forgotten to hire a conductor, and had never conducted in my life. I looked at the clock and realized that nine o’ clock was hitting, 9 AM, and there it was. The copyist took the music and I went, “Oh no, I forgot to hire a conductor, what am I gonna do?” And someone says, “Well, conduct.” Well what is one, aim down, eight out, over or…? [I laugh] And he said, “Just follow my foot,” my friend Jesse Levy the cellist. So I spent most of the session following his foot and the orchestra followed his foot and we got through it. And it was about 14 minutes of music recorded in a three hour session. And you didn’t know then. I feel like Mel Brooks, 2000 year old man, [old Jewish voice] “Back then we didn’t know, we didn’t know it was eloquent.” It’s kind of spontaneous music-making which is the kind of music-making I exalt in. I’d much rather be playing spontaneously than belaboring a point. I know people who have perfected their instrument to such an extent that the whole action’s gone. They used to play better when they were 15 year-old kids who didn’t know shit from shinola about what they were doing, that didn’t question every note and every extension, every breath, every fingering. It’s important not to. Once again, music is about communicating, what you don’t want to communicate is your paranoia about playing the instrument, but your pleasure at being able to make a joyous noise on something and that’s still how I am. I just hate putting dots on paper, night after night after night.

So let me get this straight: your first experience at film scoring was very spontaneous, but you didn’t know better but at the same time you didn’t know what you were missing.

No, I had no idea.

But at the same time you liked that way better.

No no, it was just more natural and I’m glad it was a natural evolution. There’s an expression in England that ‘fools rush in where angels fear to tread’ and I was a happy fool rushing in, there’s no reason why I couldn’t do it. Now the mechanism… you saw what’s going on in that studio, I’ve got my dear friends working overtime and I’m working overtime to finish a film that will amount to about two hours of music –

Good God.

… that we should be able to record in about three hours, old style, and we’ll spend weeks in front of an orchestra trying to get it right.

‘Cause you’re more anal, or the players are…?

I guess I am, thank God, a little more demanding than when I was 19. [chuckling] The pleasure of just hearing a noise from an orchestra is just not as profound. Before I wrote “Don Juan” I was very highly critical of my own work: there’s no air, there’s no life to it; yes it is a talented guy writing music and very energetically pounding away, but there’s none of the grace and beauty and great confident attitude you get from listening to a serious piece from Brahms, Beethoven, or Bach. Not that I aspire to be those composers because I don’t, I haven’t got a hope. But I do do the same job and am working in their tradition, and it is that rather trifle than to be music by Van Cleave, or whatever those names were they used to have on ‘50s television shows, those sort of one-named guys who make music.

Kamen.

Yeah, Kamen. K-Man. [I laugh] I’ve always aspired to some greatness in making music in an orchestra. The combined talent on that floor is inspiring, it’s not daunting and it’s a great resource to have access to. I’m lucky to be able to stand up in front of an orchestra. I just want to live up to their expectations.

You just want to please the orchestra.

Yeah, really. Give them something to play so they can all walk off the stand going, “That was good. That was nice.”

Feel the rush.

Yeah, yeah.

That’s what I can feel in your music. As someone put it, there’s an adrenaline rush.

I get adrenalized by music. I’ve walked onto the floor of an orchestra with no sleep having worked all night, barely able to talk, and yet when I stand in front of an orchestra, I am adrenalized, I am suddenly brought to life better than any illicit drug you could dream of. It is, I guess, what I’m on the planet for, to make music, and not many people, thank God, [laughs] have the opportunity presented to them that I have. It is magic to stand in front of a symphony orchestra and get the greatest musicians in the world to play your music for you.

My older brother, when he was growing up, played guitar, classical guitar, and was a great admirer of Julian Bream. We had Julian Bream records for breakfast. I didn’t have to do a thing, it was a completely passive experience for me because he went and found the records, found the cuts and played ‘em. I didn’t even know how to put it on the machine, but I did enjoy every drop of it. And so many years later I’m doing “Don Juan” and I really need a classical guitar player for this and somebody said, “Why don’t you call Julian Bream?” I said, “Come on,” and thought, “Why don’t I call Julian Bream?” So I did. And to my delight he said, “Well, send me the music and I’ll have a look at it.” That stopped me for about two months, intimidated by the thought of actually writing notes down that Julian Bream would see. And I was so sure he’d call me up and say, “Rubbish, [laughs] what do you need me for?’ But instead he was his normal, gracious self. He was very complimentary and he agreed to do the sessions and I brought my brother in from New Jersey, brought him to England and be in the same room. And it was a great thrill. Music affords so much pleasure. I know what it’s for and it is to make us feel worthy of being on the planet. To remind us of the meaning of our existence, to somehow enrich that existence. I do know that that keeps people young, keeps people vital. That’s what it’s about. It’s very distressing to see it become such an overwhelming commercial sort of fodder for the brain-dead.

Factory-made.

Yeah, such a commercial enterprise that any old piece of rubbish will come out and it will get on the radio and people will celebrate it and it’s all good times and let’s party and all that. Music is about a lot more than that. It’s not good time, it’s great time.

Most people never even get that about music. Either they don’t feel it or they just miss the boat or don’t connect.

Well, I don’t know. I think great music has a profound effect on people whether they know anything about it, whether they are aware they are listening to it, whether they’ve experienced it before, whether they are jaded old farts who can’t respond to anything. A piece of great music is such a powerful work, nonverbal communication of ideas and emotions.

Universal.

Yeah, it is universal. I will never stop being deeply gratified at listening to a great piece of Bach or playing a great piece of Bach. It couldn’t be more of a thrill.

I guess I’m saying many people aren’t even conscious of it. They’ll feel it but…

Well, they’ll feel it, but I’ve had the most bizarre reactions. I once played oboe in the middle of – I was visiting a girlfriend in the middle of Puerto Vallarta in Mexico. I was a kid, 16 or 17 I guess, and I brought my oboe with me which oboe players tend to do. Thank God it’s portable. I was playing and I became aware of somebody in the jungle and there was this Indian, a Mexican Indian of some kind, I don’t know what. I’d be really surprised if he had ever heard an oboe before but he slowly came out into a clearing wearing a traditional tribal gear and was so obviously taken by the sound of the instrument, by the notes. I don’t know if it fit anywhere with the language of his people but clearly he was responding to it, and that was an innate experience. I also live in London in quite a tall house and when I come downstairs I pass the piano, so almost every day I sit at the piano and play a little piece of Bach or something, a nice cheery start to the day. And I came downstairs and we had a nanny at the time who was what we call a goth, she had a white powdered face, weird painted eyelashes and eyelids and black hair.

A punk.

Beyond punk into the goth period, the punks just had lots of skin piercing and body piercing and stuff like that. These were another breed, these were like Laticia of the Addams Family. [I laugh] That breed of a person. And normally big Siouxsie and the Banshees fans.

What about the “Die Hard 3” album? [cutting off the goth nanny story]

It will be a classical record, not a soundtrack record. We have a bit of Beethoven on it, a bit of Brahms. My big conceit in this movie was, you know Beethoven’s 9th was “Die Hard 1”, Finlandia was “Die Hard 2”, because it was snow and the director was from Finland. We don’t need much of an excuse, just the tiniest glimpse. [I laugh] And in “Die Hard 3” I said, “You know what would be really funny? It’s a pity Beethoven didn’t write a tenth symphony but everybody calls Brahms’s first Beethoven’s 10th. So I’m using Brahms’s 1st and leaning on it fairly heavily. The problem is the director doesn’t think that theme is as well known as the Beethoven theme. And we’ll have to go back to the Beethoven theme. [This approach was evidently abandoned in the final film – LK]

Well I don’t know it by name, so…

But you know the tune, it’s… [plays it]

Oh, you mean happy birthday.

[with fake condescension] No.

So why the Seattle Symphony? Is that your first time working with them? [The “Die Hard 3” film company, Cinergi, wanted to save money by recording the score non-union in Seattle; we’ll have more on this in an upcoming issue – LK]

No. I’ve worked with them once before. A very old school friend named Gerard Schwartz, one of the most renowned conductors of American music, is the music director of the Seattle Symphony. He was simply put the best trumpet player in the world when we were going to school. I knew if Gerry was in charge of that orchestra, it’d be great. I can see going to Seattle where they have a brilliant orchestra, a beautiful room to record in, but no recording equipment, you have to take a truck up there to record. But that’s okay, we’re all rock and rollers at heart. The quality of the playing is brilliant, the people are sweet and the town is nice. But “Die Hard” is a particularly energetic LA kind of movie and I should be working with the LA musicians who made “Die Hard 1” and “2” happen, and who make all my scores happen when I work there. I work a little bit in London but that’s to be expected because I live there. The playing and the rooms and all of that is great in London but this town is made of the super athletes and the super musicians of the film industry.

They’re used to playing that type of material.

They can turn on a dime, there’s nothing they can’t play. Take one and two are always better than take ten because they’re excited. By the time they get to take ten, they’re bored. But when they first sit down it’s like a point of honor, “I will not make a mistake, I will not miss and cue and I will play like a god,” and they didn’t.

It’s a mentality.

The mentality here in town is irreplaceable for a film with as much guts and blood in it. I don’t mean the blood and guts of a bunch of guys getting shot to death, I mean the blood and guts of a piece of music. I agreed to do this movie because I felt that I had a body of work to draw on, a body of work to expand upon and a director who I enjoy working with. I like Bruce Willis; Sam Jackson is a great actor. Everything about it is to be recommended. Jeremy Irons is fabulous. And the film is pretty good… I’d cut my right arm off now to get off the picture.

Really?

You know, “Who do you blow to get fucked in this town?” is David Sanborn’s expression. [I laugh] I think that we’ve been served badly by… [I say something, tape recorder sucks] Yeah, I don’t think you should print that unless you attribute is to David Sanborn. This film is about commerce so you can’t fault them for wanting to save money, but the techniques of saving money are ratshit to say the least. It’s false economy. It will probably wind up costing them more at the end to record in Seattle than it would have just to do it here. There’s union problems, there’s problems with orchestrators, the people I normally rely on are not available to me. I don’t blame the union, my parents fought long and hard for the union cause in the ‘20s, 30s, and 40s and I’ve always believed in it very strongly. I think the principles of bargaining are existent and I don’t think the union is really lifting a finger to try to come to terms with what is a general problem. Like many other things the field of play is changing and it’s very expensive to record a score in LA. There are many, many films that can’t support the kind of freight that’s charged by the LA unions. In a nutshell it boils down to gong to Seattle and knowing that I can have an artistic great time with the orchestra. I can eat very well but I’m missing my friends and I’m missing my due to the dictates of a company that won’t work it out.

So McTiernan has to fly up there…

McTiernan wasn’t on site when we recorded. He was in fact in Baltimore shooting the last reel of the movie when we were up in Seattle last week. He’s a very trusting guy and has always left that to me. He responds to the music and he moves it around and uses it where he sees fit. Sometimes he comes up with novel ways of treating a cue. He loves the humor in the score, he likes the tongue-in-cheek quality, because you can’t have just fruity kidding around, “Only kidding guys.” The music kind of has the personality of Bruce Willis in the film and that’s a larger-than-life personality.

Oh I’m sure. Was he at your birthday?

No, no, I had a very small birthday this year. I have a lot of friends in this town but I’m so wrapped up in the middle of this film. It would’ve been insane. I couldn’t have afforded the four days’ recovery that I need at the end of one of those. [laughs, I laugh too]

I got ya. So are you British or what?

No, I’m a New Yorker. And this movie takes place in New York so I feel…

But you’re very British…

Well I’ve lived there for about 15 years. And my wife’s British and my kids call me diddy… Britain’s my home and America is my land of opportunity.

It must have been cool on Die Hard 3 to be in New York.

Well the cool thing is that a lot of it takes place on that streets that I inhabited. There’s this place called Gray’s Papaya King that I always used to go to, to get hot dogs and papaya juice, that’s just off the 72nd Street subway station. I was trying to figure out what music I could put there and I realized Needle Park is just up the street and all you ever hear up there is bongo players and people driving past, and that’s why that cue is all native percussion.

You’re not using synth there, are you?

No, no, I won’t use the synth, we’re using drums and drum loops and, you know, the normal accouterment of a modern recording studio, even a live drummer from time to time. But the question remains whether I’ll use an orchestra at all, or just do the whole cue with drums which is kind of interesting.

Oh. And he [McTiernan] originally wanted no music at all there?

He didn’t think he needed music in the scene. His idea was to keep the music a little sparser in the front of the film, because by the end of the reel it’s just wall-to-wall, there’s never a moment you can stop. You’ll never take that cigar out of your mouth, the Groucho Marx line. The idea of keeping the music deliberately out of the way was very appealing, but New York is never without music on the streets. So we’re having cars drive by with reggae booming out and steel drummers and sax players and stuff like that. But that’s the design of the film.

So you’re doing a lot of source cues.

Yeah, they’re not even cues, they’re just, “What was that?” They’re just music concrete, concrete of the city streets.

Everybody knows for the action, and we talked about “Die Hard” to death… I could talk about it forever.

You’re one of those two guys who will really like that movie.

[I laugh] Yeah, right.

When I wrote a saxophone concerto for Dave Sanborn I was going…

I have that.

Have you? Well then my story’s no good anymore, [I laugh] because I was going to Ireland to record The Chieftains on “Circle of Friends” and I bought a ticket from the guy from the Air [something] counter. And he looked at my credit card and said, [Irish accent] “You wouldn’t be that Michael Kamen who wrote that saxophone concerto for David Sanborn?” And I said, “Do you have that record?” He said, “Ahh, yes I listen to it all the –” I said, “You’re the guy, you’re the one that owns that record.”

But even that sounded, I mean, your albums always sound incredible.

Well that’s Steve McLaughlin, who you met sitting behind my Kurzweil trying to make out that he’s a modern drummer instead of the best recording engineer in the world who also happens to be a modern drummer. He was in a punk group called The Cars and he was a drummer. I met him when he was flogging musical instruments at a place called Syco in London; he came by to help me fix my Kurzweil one day and we’ve just been dancing ever since. He came to work for me on “Someone to Watch Over Me” and he’s been on everything I’ve done since then.

That’s great.

He’s an incredible engineer and more important, he’s been a fabulous guy to have around and he keeps it fun. Great perspectives and he’s tireless, he never stops. So that kind of matches my energy and we have a good time together.

Let’s talk about melody. So was it you that came up with [I hum the Lethal guitar theme]?

No, that was Eric. He came up with that and I was the guilty one saying, “Is that all?”

I loved how you mocked it in Action Hero. You had fun with that score, I bet.

[emphatically] Yes, I did. I really did. I liked that movie. I really loved the movie, it had a couple tragic flaws in it, mostly the bad guys who just weren’t bad and that’s the formula for these movies. If you get a great bad guy, then you’re cheering for the guy who wins. And if you don’t, I mean if you have Anthony Quinn as a bad guy, he’s everybody’s favorite grandfather. He’s not gonna be evil and you’re not gonna wish him dead, you want him to go on forever, [louder] “And do that little dance you did on the beach, would ya?” It’s unfortunate that movie wasn’t given the right time to homogenize itself. Again it was McTiernan operating at the top of his form and making a very wry comment about the movies that have been elevated to some level of esteem in this town. I guess you can get a little too pat about what you’re mocking. You know, [chuckles] don’t bite the hand that feeds you. But I really did like that movie and it was an opportunity to have fun with the music. I thought it was a very sweet film.

Well, the contrast between the reality and the movie was interesting. And you both used very different styles in each.

That was one of the conceits of the film, one of the operating levels, to try to be in and out of it. For the most part it worked and we never got the film long enough to aim a shot at it, it was always being cut. After a while we stopped calling them changes, we started calling them improvements. “Here’s reel seven with improvements.” And they’re not always improvements but everybody’s working so frantically to make the deadlines, quality and sense, very often, are the first things to go.

That was a great album.

Thank you. There was a lot of score in the score album and there was a lock of rock and roll in the rock and roll album. They worked consistently together and it was nice to get them to do that.

So what was it like working with Pumpkinhead?

[laughs] Buckethead, Buckethead.

Buckethead, sorry.

Pumpkin… there is a band… oh, Smashing Pumpkins, Buckethead’s a great cat – I love rock and rollers. I have to say, my God, so is Eric Clapton, he always was, and to have him as a great friend is a thrill, an honor. He is a fabulous musician, and I don’t idolize him because he has a nice chin, I love him because he’s a phenomenal musician and to get to work with him is unbelievable. I don’t know how to describe that to anybody without sounding like a fool but the first time I played with him, I mean, I probably sat at a piano playing rock and roll bands for 20 years at that time, and I’m always trying to get the guitarist to do what I hear in my head. Time after time after time they couldn’t do it because they weren’t Eric Clapton, and that first day that I was actually sitting at the piano and he was in the other chair playing guitar, everything that came out of his guitar was… I was sweating because there it as, just like I’d always pictured it.

It lived up to expectations, then.

It exceeded expectations.

Was that yours or Donner’s…?

N-n-n-n-no, Eric, and I had met on a Roger Walters record. When I was working with Floyd, I formed a relationship with Roger. He left the group and decided to make a solo album; actually he didn’t even leave the group, at that point, he was still in the group but made a solo record. He needed a guitarist and you can’t fill Dave Gilmore’s shoes very easily. He was a friend of Eric’s, I didn’t know Eric, and he brought him on. Eric wasn’t very busy in those days. He’d had a peak and another peak and another peak and he was resting in between peaks, I guess.

He came in and played and it revolutionized by life in many, many ways because for the first time I found myself not trying to guide the man from the piano, but just listening to that guitarist and seeing, oh my hands are moving. That was the true meaning of playing in a band. It’s not trying to play everybody’s part on the piano so they get it, it’s combining with what you’re actually joining forces with. We discovered to my thrill that we have a love of blues in common and a knowledge of blues in common, and I was intrigued by his playing, his master of his instrument and him as a guy. When we finished the tour with Roger, I went off and did “Brazil” and I brought him to the premiere and he liked the movie. He liked what I had done, and about a week later he got a call from somebody at the BBC asking if he would score a television show for them. He looked at the television show, loved it, but realized he needed help ‘cause he’d not ever done a movie, and he thought of me because he had just seen me in that context.

So he asked me if I’d be interested in working with – “Yes!” Before he had it out of his mouth it was, yeah. He came over to my house and described it. I remember thinking, isn’t it too bad that what he’s describing it a small BBC television show and nobody’s gonna see it and that’s a pity, but I’ll still get to work with Eric. We started looking at the movie and it really was a strong piece of television, probably the strongest piece to come out of England in 20 years. It was a show called “The Edge of Darkness” and we did a lot of music for them, we were supposed to give them ten minutes of music and it’s a six hour show and six weeks of installments and we probably scored the whole thing. When it was over we had some pretty extraordinary music. It was the first time I had a Kurzweil and I was making strings on the Kurzweil – Eric would just be jamming and I’d be playing and we came up with wonderful ideas.

So you guys just improvised like crazy.

Well we made the theme, we picked it out and it was fun to make a theme with somebody like that because he’ll come up with a line and I’ll say, “Oh yeah, that goes here.” It’s like a jigsaw puzzle where we each see the inevitable mixed idea from the seeds of the last idea, and are very compatible that way. So we finished the score, we knew we had done something very good, I was really thrilled with it. Again, I though, isn’t this a pity this is gonna be a simple primate television show? But the show wound up coming to acclaim in England. There was a guy at that time named Stuart Baird, an English editor who was working in Hollywood editing “Lethal Weapon 1”. He remembered the music that he heard for “Edge of Darkness” so he got hold of a CD, or at that time a tape probably, and used our music from “Edge of Darkness” to temp-score “Lethal Weapon”.

I didn’t realize that Lethal Weapon was actually your big break.

Yeah. I thought that I had a career with “Brazil”. I thought when I did Brazil that I’d be, you know, noticed in this town but it was, “Uh, and you are?” [We laugh] They only notice you if your movie’s a hit. And within minutes of “Lethal Weapon” soaring to the top of the charts that week, I was getting calls from famous directors.

So Richard Donner, I guess, that was…

That was before, this is Donner being a brave man. This is Stuart Baird saying, I have an idea for this movie that the Mel Gibson character should be portrayed by a guitar and I have these tapes of this guy Kamen who did this thing with Eric Clapton. They used “Edge of Darkness” very extensively to temp “Lethal Weapon”; I had never done a film like that before and I hated the script and I didn’t want to do the movie, but Eric liked Mel Gibson, so I came to town to spot the movie.

You hated the movie?

I didn’t like it. [I laugh] I mean I saw a very early cut and it’s not my kind of movie. I don’t actually like those kind of movies. I like “The Wizard of Oz”. The idea of Eric and Mel Gibson working with good chemistry was fantastic and then he made what could have been a terrible mistake, because at that time and to this day and probably for the rest of my life, there is only one saxophonist living who is worth speaking about. And that’s Dave Sanborn. And Dave Sanborn is a great, great friend.

You had worked with him before, then?

Oh yeah, sure. Dave Sanborn, he was in my New York Rock and Roll Ensemble 20 years ago, or whatever it was, and he’s taught me a lot about music, although I still to this day know nothing about jazz and he’s never stopped digging at me about that. But Stuart Baird said, “I wonder if you think this idea makes sense: you could have a guitar for Mel Gibson and then Danny Glover’s character could be a saxophone,” and I said, “Well that’s a brilliant idea.” Because I’ve always done that, assign instruments to a character, it just makes it easy.

Not just a theme but an entire instrument.

Well, it’s “Peter and the Wolf”…

I’d guess I’d be the Styrofoam cup.

[Laughs] It’s a good job, you can’t get that job. I became very cautious because there are a lot of saxophone players in the world or would-be saxophone players in the world. And he says, “Well I have this guy in mind,” and I immediately went, “Yeah, who?” very very defensive. And he said, “Well, I don’t know if you’d know him or not but I heard him play the other day and he’s great.” And I went, “Yeah, who?” [I laugh] He said, “His name’s David Sanborn,” and I said, “You got it.” So the idea of bringing David and Eric together, two or my favorite musicians, the two leading exponents of their favorite instruments, these two major lead instruments of rock and roll… for me to be the cement that got them together is an honor. And to be in the same room with them and play with them, is… are you kidding?

So you weren’t friends with Donner, then?

No, this was the first meeting with him. And Joel Silver. I loved them from the second… they were immediately recognizable as the real thing in the town where it is easy to hide deficiencies behind an expensive car or expensive sunglasses. These were regular guys.

He’s been loyal to you.

Dick?

Silver.

Yeah, and Joel too. Absolutely. I hope we continue that on a mutual level. He’s a very, very tasteful, sweet guy, who makes some very untasteful, unsweet movies, and whatever he does I’d like to be a part of.

So you’ll be doing “Fair Game”.

I probably will.

And “Assassins”.

And “Assassins”, yeah, probably.

The first “Lethal Weapon” album, did it have that big chase cue at the end?

I don’t know, everybody talks about the big chase cues, I don’t remember them.

You know… [I start mimicking the cue]

Yeah, but they all sound the same [I laugh] It’s “Mission: Impossible”. “Lethal Weapon” was the beginning of the end ‘cause it was the first time I ever worked with orchestrators. Up until that point I had a very purist attitude about…

You didn’t know what…?

Didn’t know what they were. And then on “Lethal Weapon”, the night before the last session, the copyist introduced me to two orchestrators. I was one of those guys who didn’t do his homework if he could get away with it.

As far as bombs, I mean, “Last Action Hero” was a bomb. Did you know as far as that, or “Hudson Hawk” or…?

No, you never know, you can’t work on something knowing it’s gonna be a disaster. You work on something hoping it’s gonna be a success. When something is that big a bomb, it’s a 50-50 proposition, it could fallen either way.

The filmmakers didn’t know or…?

I think some of the executives knew. But before long… so long down the line there’s nothing they can do about it.

Talk about your percussive style.

It’s very, very simply. I always had a piano in the middle of my living room and I have three brothers and they always had a bunch of friends over. My mother has a loud voice, my father is always telling jokes and stories. My piano wasn’t very good and in order to get the sound out of it, I had to bang it. And my entire life my mother would say, “Michael, stop banging on that piano!” And now I bang on the piano for a living.

And just translate that to orchestra.

Yeah. I’m actually learning to play soft. I have a harpsichord and I’m learning to play gracefully and softly.

I just love the way the bass and power…

Well, so do I. [laughs]

Just making sure you know that I know…

[Laughs] Oh good. Well it’s very flattering to me that it’s been spotted. It’s cool to get it spotted. Well-spotted is the expression in London. When somebody notices something, you go “Well-spotted.”

So after “Lethal Weapon” you had an onrush of – obviously in ’89 you had like one movie after another.

Yeah, well, I did run a rock and roll band on my personal credit card for about eight years and was so seriously in the hole that the word “yes” was all I knew. When somebody offered me money to do a project, “Yes! Okay.”

It’s like Samuel L. Jackson…

Well, you know, that first fluster of success is… is remarkable. You don’t ever want to say no, you want to be able to do it all. You don’t have panic attacks about schedules and you can do it all in your mind. And so you take it all on. I probably did too much at that point, but that’s common. That’s the way it goes. At this point I have to rein myself in and calm down.

You did “License to Kill”, then. Was that a good experience?

Yeah, well, a Bond movie.

As far as the producers, etc.

Well, Cubby Broccoli is an amazing human being. And his daughter is a sweet… well I wouldn’t say sweet but a remarkable person. It was great to spend time with her. It’s nice to be part of what is essentially a mom and pop business. That’s the Bond movies. It’s the family store. They were welcoming. I was sad because the reason did it was that John Barry wasn’t well. They didn’t do it [hire me] because they wanted to replace him, they did it because he couldn’t do it. And that’s his meal ticket. He should be able to eat at that table whenever he wants to.

I think he’s awesome and I think you’re similar in that you both have a fullness to your orchestra. It’s just there, the texture…

He uses more horns than I do. [laughs]

Well, if you’re gonna be specific. And Gilliam: Are you gonna do “12 Monkeys” or what?

I don’t know, I think he’s gonna use a very classical score.

Oh really?

I don’t know. I do not know. We’ve spoken very briefly about it and he typically doesn’t make up his mind until he’s seen his movie… which is the way it should be. Unless you know in advance what it’s gonna be. But Gilliam’s kinda like me, or I’m like him in that regard. He doesn’t have any clear idea, until it’s finished, what it’s gonna be any more than I do.

And you didn’t do “Fisher King” because…

I didn’t do “Fisher King” because he didn’t want to use me. Period. I think he was pissed off at me for doing all those movies in ’89. [I laugh] He’s still working on a script for that one movie and I’ve finished 15 films. And he’s not wrong. “What are you, nuts?” He’s one of the few guys I know who makes a point of living below his means. And is the warmest, sweetest, most brilliant human being I’ve ever hoped to work with. I think he’s the best director alive.

Really?

Yeah. He is phenomenal. His energy is so relentless and magical that it’s childlike and I like that childlike aspect. I miss him. I hope I get to work with him and I’ll be very upset when I don’t. I was really burned on The Fisher King. Really upset. But I’ve gotten over it and I’m sure he was right. And I won’t go to see the movie.

[We laugh] Not that I’m bitter but…

Yeah… fuck you.

Never heard of it.

Yeah, Fisher who?

So why aren’t you doing “Waterworld”? [I laugh at his reaction]

I think the rhetorical answer to that is why are they doing “Waterworld”?

Well, you worked with Reynolds before.

Yeah, I liked him, we had a good experience. Then he was fired, so he and I had very little common ground on “Robin Hood”. And he would’ve I’m sure exerted a very powerful influence on the score. He did call me when it was all over and thanked me for the music because he liked it. I loved him. He and I had the same kind of vision of Olde England. I wanted to make that score out of sackbuts and shawlms and really old instruments and he was all for it. The guys at Warner called me into their office and said they’d shoot krumhorn players on sight if they saw them walking outside the studio. They wanted a big orchestra.

You’re typecast, not really typcast, people know you, they go, “Michael Kamen, he’s the action guy.” But your bod of work, that’s like five percent of it.

Thank you. It’s just what Hollywood does. In Hollywood, everybody needs to have an opinion, that’s what the town is based on. If you have an opinion about an actor, about a screenplay, about an agent, about a property, or about a price, about a deal, then you’re valuable. If you’re one of the guys who say, “I don’t know,” then they don’t talk to you anymore. Everybody in Hollywood has an opinion and therefore they’re head over heels in a rush to typecast everybody, so that they can identify everybody in a synopsis of one syllable or less. Um, how many syllables in ‘asshole’? [I laugh] The, uh… [laughs]

Those are easy to typecast, they’re everywhere.

Yeah, they’re all over the place. Chris Brooks, my music editor, has the fond expression that everybody in Hollywood has two jobs, theirs and yours. It’s easy to be cynical about this city. People do lose their hearts and their minds in this town but it’s also filled with wonderful, fun-loving, creative people. Three of ‘em. [I laugh] No. It is possible to be very cynical and I have to guard against it because it’ll stop me from writing music. I’m fond of saying these days that I know who I am and it doesn’t matter to me if people identify me as the guy who writes music for shoot ‘em-ups. I’d much rather be known as the guy who wrote the score of “Brazil”. That’s work I can stand on. The guy who worked with Eric Clapton, the guy who worked with Pink Floyd, the guy who worked with Queensryche, the guy who worked with Alice in Chains, and works with Pavarotti, and Sting… those are my pals and those are the people that I… I love ‘em. My great heroes, the people responsible for my disillusion into rock and roll are the Beatles, and to get to know them, to be a great friend of George’s and Paul’s is worth a lifetime of joy. It is true that I think I’ve squandered some of my abilities on projects that probably I should have stayed away from, but you know what, everything is fun, there’s always a justification and it’s not ever the money. It really, really, really isn’t the money, because they couldn’t pay me enough to do this job. And they do pay me enough to do this job. [We laugh] Thank God they do pay me because I like the benefits of hard work. But I love Joel Silver. I love Dick Donner. They’ve become great friends. If they call me and ask me to do a movie, I know I’m gonna hang out with ‘em, I’m gonna spend time with ‘em. I’d write something every day anyway. I always write, I’m always writing stuff and I hope I continue to do that. If I get cynical about either my business or my life or my situation in L.A., I’ll stop writing. That cynicism will arrest me, not bad reviews or bad movies or even bad scores. At least it’s a try and I get to stand in front of the orchestra and say, “Well, that wasn’t so good, was it?”

My delight is in making music and knowing a lot of people, and working with a lot of people. I suppose as I get older I might even be getting wiser. I’ll be a little more deliberate about the movies I do and the music I write. It was a surprise to me to have written the “Don Juan” score the way I did. I didn’t just improvise it and put it on paper and then record it. I gave it a great deal of through and effort, and kept weeding it out, trying to make the lines straighter… to me. It may be very confusing to everybody around me but I know what the cue meant. I’m real happy with the position I’ve reached musically at this point. Career-wise is anybody’s guess. I don’t know how people would think about me after I’m gone and if they’ll think about me after I’m gone. And I’d like my children to not think of me as the guy who wrote ““Lethal Weapon” and “Die Hard” but as the guy who wrote “Brazil”, “Don Juan”, “Robin Hood”, and “Circle of Friends”.

There’s another movie coming out in the fall called “Mr. Holland’s Opus”. At the moment that’s probably gonna have a name change but even if it doesn’t it’s a great film with Richard Dreyfuss playing an American musician who starts his career in the ‘60s, wants to be the great American composer and winds up having to teach school to make ends meet. It’s the saga of his life, a 30-year life teaching school. He doesn’t become a great teacher, he becomes a mentor. I’m lucky enough in my life to have phenomenal mentors, people who showed me the way to live. Not the way to make music but the way to think and fell and trust my instincts, and there’s so many of these teachers that come to my mind. I had a piano teacher whose name was Lewis Carroll and I was sure I was studying piano as a kid with the guy who wrote “Alice in Wonderland”. He was funny and remarkable and he started me on the oboe. A guy named Fret Leitner and Gene Steiker, Morris Lawner, these are people who had a profound effect on me and “Holland’s Opus” is about that exact thing. So I wrote, I think, a bunch of really good music for that and at the same time got to play a Bach harpsichord concerto and a Beethoven symphony and it doesn’t get much better than that.

Sounds like that’s just thrown off your feet, just came along and the orchestra was there…

I took to it like a duck to water. I do shoot from the hip. I don’t really agonize over things. After all, especially in a film score, you’re gonna hear it once if you hear it at all and it has to have an immediate effect. No amount of agonizing over an idea is going to produce an immediate effect on people. If it doesn’t produce an immediate effect on me, who’s it going to impress? So in many ways a film score is a lesson in coming up with instantly memorable music or instantly effective music depending on the situation. You don’t exactly need a melody for a train wreck but something about it… shouldn’t confuse you. You should know what world you’re in, what you’re inhabiting and what world you’re about to inhabit or you should be wondering 90 miles a minute to try to figure out, “where’s it gonna go?” Whatever music can do it should do. And what it shouldn’t ever do is descend into the kind of morass of 20th century pseudo-political, politically correct modernity sanctioned by the music schools. They’re training a whole shitload of musicians who will never see the light of day and who are writing music no one will listen to and if they do they’ll want to turn it off. I have to believe in melody, I think it’s driven people for a reason, and that is the language of the human spirit, and we haven’t changed as human beings in the last couple of million years as far as I can tell. I’m sure that people have always felt the same kind of joy and anger and sadness and profound feelings and that’s the way music is meant, it doesn’t change simply because you enter the 20th century, that’s a godawful conceit. Even Schoenberg excused himself one day. When someone said, “Aren’t you Arnold Schoenberg?” he said, “Yes I am, but somebody else would’ve been if I wasn’t.” [we laugh]

Most people who have this type of perspective, if anywhere, L.A. is gonna take this away from you, this…

But I don’t live here!

That’s right, well that’s good.

[laughs] I’m only a visitor. The music business, whether you’re a rock and roller living in Minneapolis or a shitkicker trying to play bongos in New York or a film composer sitting in L.A., the business of making music is completely anti-thetical to the goals… Music was not invented to make people rich, to keep people dancing or to sell soap on the radio or television for that matter or to accompany an elevator ride. That isn’t the purpose of music. It’s for planting corn and for making love and for celebrating the birth of your children and the death of your parents. The things that make life profound are the things that make music work. I don’t take the business of making music seriously. I’m either just lucky or maybe I’m talented. I don’t know. But I haven’t had to struggle to make the music I want, it just seemed like a clear path, I never veered from it.

My father made a great statement recently. I have a fabulous aunt who’s a rare human being, she’s 90 years old, just turned 90 and my earliest memories are going to her house in New York City and seeing string quartets playing in her living room for a group of people who were affably discussing the Mozart quartet they just heard over the most delicious Russian Jewish meal they’ve ever eaten. It didn’t occur to me at that time that these guys sitting there were the Juilliard String Quartet, or that these were some of the world’s greatest classical musicians assembled in her living room out of love and out of eventually a desire on her part to raise money via these private concerts for a thing called Camphill Village, which takes care of autistic children from childhood to adulthood. She raises a great deal of money and has musicians play on their behalf. It’s always a wonderful feeling to play music for the right reasons and there are never more right reasons than what occurs at Aunt Anna’s. So I was playing her 90th birthday party in New York, we had some of the world’s greatest musicians there: Richard Goode and Glenn Kissin and Charlie Woodsworth and Charlie Hamlin and Pinky Zuckerman, and everybody played and I played oboe. And my father budged the guy standing next to him and said, “He’s so good, if he’d only kept it up, he could be starving by now.” [we laugh] It’s that sense of humor and humanity that I think has to guide one through life and I’m just blessed to have it in abundance.

… Well, you glow with it.

Well I glow with it right now because I just spent the afternoon with me daughter.

I got you at a good moment.

You did, you did… and I’ve had about three hours sleep because someone turned in a cue [picks up ¾ inch thick written cue and drops it] that won’t even burn properly.

Good Lord.

Yeah. That’s a cue from “Die Hard 3” and it’s… rubbish. And that’s what it will be [flips through pile of blank paper, chuckles] but I’ve gotta put the dots on the paper.

My God. Sucks to be you. [I laugh]

So much for me. It is “Die Hard... With A Vengeance”.

(Two weeks later, on phone) (published Dec. 1995 in FSM #64)

When I was there I wasn’t sure if I was intruding or not.

No, no, I had fun with you. Beats the shit out of writing music.

Talk about collaborating with vocal talents such as Sting or Bryan Adams.

I am by nature a collaborator. I trained to be an oboe player and the oboe is a very nice instrument but doesn’t play completely by itself, ever. So, I’m used to working with other people. Also as a rock and roller, you’re good in a band with other people; as a ballet composer I always worked with the choreographer heavily, making sure the dancers with in sync with my counts and music and stuff like that. I like collaborating.

You’ve done a lot of ballet composing…

Yeah. So the idea of working with Sting is exciting because I love his work. We’ve become friends over the last few years and I love working with him. He’s a great collaborator. He took several of our ideas, Clapton’s and mine from “Lethal” and I just sent him a tape with about 15 ideas on it saying please respond to something, let me know what you think. And he picked the one thing on there that I felt was viable and he said, “I can do something with this.” As expected, he did something totally unpredictable. He used the melody. He built the song on top of the song.

Oh, so you gave him the theme, so to speak.

I gave him the theme and the rhythm in a form that was organized to be a sort of pop version of the “Lethal Weapon” theme. And he added a whole lyric on top of it.

That’s great.

We all realized that it was kinda difficult for Mel Gibson and Danny Glover to be singing a love song to each other.

[I laugh] I know…

And Sting nailed it. You need somebody with that brain to go, yeah, you know when you need a friend and when you need somebody to protect you, ahh fuck it, it’s probably me. I wish it wasn’t but it’s probably me, and Sting had that great implied “fuck it” in the song which I loved.

People might’ve thought it was weird that there was a slow song in the beginning but it really, it’s like powerful as hell.

It’s a cool song.

And people would always say, “had to say it,” but it’s “hate to say it.”

What? Oh no, no, no it’s “hate to say it.” The cool thing about it was that the sound that drives that song in at least the picture version is… you know, when Dick Donner makes a movie, he always puts a subplot in. So “Lethal Weapon 1”, the subplot was, “don’t eat tuna until they stop netting.” And “Lethal Weapon 3”… I can’t remember what the subplot of “Lethal Weapon 2” was…

Apartheid?

It was apartheid, that’s right. It was the South African problem. Which we sure took care of, didn’t we? See?

[I laugh] Amazing what film can do.

And then “Lethal Weapon 3” was the stop smoking motif. One time we were working with Eric Clapton who now is a non-smoker; he was playing guitar in the studio, but he wanted to play acoustic guitar. We had a microphone up in front of him, and at that time he smoked very heavily and had a heavy duty, gold-plated zippo lighter that he’d drag in front of this very expensive microphone and flick and close as he was lighting his cigarette. It made such a great sound that Steve McLauglin, my engineer and buddy, took the sound of his zippo lighter and turned it into a percussion track, just sampled all the different stages of the zippo lighter. And that’s the drum track.

That’s great.

The drum track for this anti-smoking subplot movie [I laugh] is driven by a zippo lighter.

That’s funny. That’s the only percussion in the song.

That’s the only percussion.

I knew that was a lighter but never… really… thought about it. It worked well. With Bryan Adams, that was his lyrics for “Robin Hood”?

Yeah. When we did “Robin Hood” that was a long distance collaboration; I’d never met him, he’d never met me. We had one conversation where I suggested the lyric that would be, “I’d do it for you,” because there’s a line in the film where that comes from. He ran with it and turned my melody into an everlasting pop song.

A very successful one too.

Very successful, having equally one with the “Don Juan” tune.

Why didn’t you do “Maverick”?

He didn’t want me!

He didn’t?

No!

Bastard!

[laughs] It’s okay. I’m doing his next one.

I figured… “Assassins”, right?

It’s great, I just saw four reels of it up in… they’re shooting up in Seattle. It’s great such a surprise. It’s really moody, dark… really strange.

Cool. But what about “Maverick”, do you think he didn’t want you for a western or what?

I don’t know. Who cares? [I laugh] Richard Donner’s a dear friend and he will remain a dear friend.

I could totally see you doing a western.

Well I haven’t done a western but as it turns out I don’t think that was the western for me. Someday I’ll do a western but I’ll always work with Richard and that’s worth more.

And you worked with Robert Kraft, is that right, on Hudson Hawk?

Oh, yeah.

Were you really collaborating with him?

Yeah, we did collaborate, pretty heavily. He was a friend of Bruce Willis’s and he had written the story. Joel Silver was gonna work with him but he was a fan of mine and he said, “If you want to bring Michael in, I’d be only too happy to work with him.” So they all signed off on that and we had a great time. I’ve done a lot of those. I did a really stupid film called Action Jackson.

Oh God.

But I got to work with Herbie Hancock.

Oh, really. Would you say Bruce is one of the more hands-on actors?

He was in that film. I think every film has its own quality and he had written that story so he was definitely part of the production end.

I was curious if there were examples of actors very hands-on in general as opposed to actors that once their job is done, they’re gone.

I don’t think in general an actor gets that kind of license from the director, and they certainly don’t look to me for their collaboration. I have on many occasions spoken to the actor involved in a film because the music is very much a part of their character. I just had a great conversation with Stallone for “Assassins”. He feels very strongly the music is a major contributor, another character on the screen, and I’ve always felt I’m a character in a movie. He was talking about Conti’s score for “Rocky”, that he felt that was well over half the movie. Where he didn’t do anything, the score did it. He was doing a movie recently where he didn’t want to have a composer hitting all the action beats and turning corners all the time. He wanted somebody who really was a master at the craft of fashioning movie music. So he insisted that they hire John Barry. I think it was “The Specialist”.

Yeah.

And he said, what a difference it made to have a composer come in who wasn’t interested in proving that he could hit everything but just made a mood. Of course, that’s sometimes appropriate, sometimes inappropriate. Sometimes the music serves the film better by hitting everything and sometimes it serves the film better by ignoring those hits.

It’s very delicate.

It was kind of unusual for me to be having that conversation with Sly and he said, “What about the character having an instrument like the saxophone?” And I said, “I love that because it’s such an expressive instrument but, in fact, we’ve kind of done that, nailed that territory with “Lethal Weapon”.” He said, “Yeah right. What about a more classical sound for this guy because he’s such an internal character, he’s a deeply tragic, flawed human being?” I said, “Yeah, what about an oboe?” And he said, “I love the oboe, it’s poignant.” So guess what, I’m gonna be writing my first oboe concerto for Sly Stallone [laughs].

That’s great.

And I’m an oboe player so I think I know where to find the oboe player. [Since this interview, Kamen did score “Assassins”, but his work has been replaced by Mark Mancina, for whatever reason. Live by Hollywood, die by it. –LK]

How’d you get involved with “Highlander”?

One of the very first films I did was a film called “Stunts” for Bob Shaye and New Line Cinema, and these producers, Bill Panzer and Peter Davis, came back to me many years later with Highlander. It was also Freddie Mercury, you know, Queen were involved with it, they wanted to work with him.

That was a good experience?

“Highlander 1” was okay. I wouldn’t do “Highlander 2” and I won’t do ““Highlander 3”, 4, 6, and 7. The first one was really cool to work on.

I bet. The contrast between the flashbacks and present day.

Yeah, I thought that was really killer, I was very impressed by it.

You were talking about mood, with John Barry. I think you’re incredible with creating mood.

Thank you. Well I’m very reactive. I have to be, that’s my take on a movie. A movie like “The Krays”, “Brazil”, or “Don Juan” has so much character of their own that the music has to serve that character. And that’s what I try to do.

And it works.

Music is about nothing except emotional mood, so I’m always able to lean on a skill at making music and music does the rest for me.

Do you have a favorite composer? Could you pick one?

Yeah, Bach. I’m very partial to Bach, very partial to Brahms, I’m very fond of Stravinsky.

And then you kind of like…

Hmmm.

You go from very partial to…

When I say very partial I’d lay down and die for them. [I laugh] That’s very partial.

That’s very partial.

Yeah. I mean, these are the great masters who really understood the language of music. I just shake my head disbelievingly when I get to hear their music, get to play their music. I call myself a composer but I’m more thrilled to be in the same profession as those people without a lick of their talent. I’m good at making up melodies, I’m good at sorting out the vicissitudes of a film. But there people made music and that’s something I can strive for because I do this same job, just not as well.

Oh stop it, you’re awful.

Well, it’s true. I mean, you listen to Bach and then call yourself a composer, it would be better to call myself a shoemaker. [I laugh]

Do you have a favorite orchestra you like to work with?

I don’t have a favorite orchestra they’re all made up of wonderful musicians who have dedicated their lives to playing an instrument and that’s always fascinating… it would be like a favorite position of sex. [I laugh] They’re all fantastic and there is no way you could…

… just pick out one.