In actuality, there have been more than four “Batman” films. In addition to the gigantic contemporary features, there are the recent animated efforts, the old 1960s TV show which spawned a movie – this featured a riveting scene of Batman (Adam West at his surreal best) beating a killer shark with his fists – and numerous black-and-white serials that predated all of this.

So, it is to Elliot Goldenthal’s credit that he is able to find new directions to take “Batman” music. His approach may use the melodrama of the original serials, the jazziness of the ’60s version, and the Germanic darkness that Danny Elfman and Shirley Walker have propagated, but the assemblage is pure postmodern Goldenthal. That’s not to imply that Goldenthal’s take on Batman is just comprised of bits and pieces of past efforts. From the inclusion of 20th century compositional techniques to his integration of electronics, he has put his own personal stylistic stamp on the franchise.

And that particular stamp seems to be increasingly popular these days. Goldenthal has just opened a new ballet of Othello, commissioned by the American Ballet Theatre. He’s racked up a handful of Drama Desk and Tony nominations for the latest incarnation of his theatrical piece Juan Darien: A Carnival Mass. And on the film score front, his score to “The Butcher Boy” for director Neil Jordan will be out this fall, featuring a combination of orchestra and electronics that’s like nothing he’s ever done before. For fans of Goldenthal’s unique and intelligent voice, it looks to be a very good year.

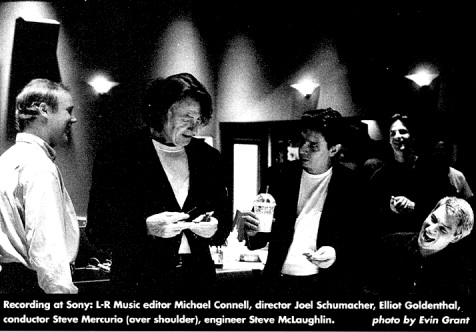

Was it basically a given that you were going to be back on this sequel or did you have to go through some of the same channels again? I know you’ve done a lot of work with Joel Schumacher as of late.

Well, it was about a year ago Joel said, “If you do it I’ll do it” – that kind of thing. And I really wanted to do the sequel because you don’t get your themes really going until the next [one]. When you do the first one, you’re kind of finding your way through, trying to break some new ground. You know, new director, new Batmobile, new Batman, the whole new thing. And then [due to] the fact that it was so successful we were able to assess what we had, and now the thematic material from the last one can really breathe in this one. Of course there are so many new characters that there are many, many surprises and about an hour-and-a-half of very fresh, new themes.

In your past “Batman” score every character got their own little microcosm of musical devices that we associated with them. Is that going to be your approach again this time?

It is. Batman’s theme is still Batman’s theme and there’s like a ‘trouble in Gotham City’ kind of thing that we might have heard, and it might be variations on. But, Mr. Freeze has this grand, orchestral/choral theme that sometimes is in German, sometimes is in Latin.

Is that German text Schwarzenegger leaking into the character?

Yes! Of course. Poison Ivy plays both a nerdy sort of environmentalist and a very sexy film noir type of character, so she’s got both types of approaches musically. A very sexy film noiry saxophone thing goes with her. Then of course you have the characters of the stage sets and Gotham City and all of these being characters in their own.

Now, tell me if I’m hearing wrong, but I’d heard that the Robin character will have a theme this time.

Robin has a theme. It starts to develop more and more as the picture goes. At one point they flash the Bat-signal on – Robin flashes it on and pisses off Batman because he flashes the Robin signal. So you hear Robin’s little logo thing there.

When you’re doing this kind of character scoring, how much are you trying to do a musical representation of what you see on the screen and how much of it are you trying to add things to the characters and flesh them out?

I think it must be about fifty-fifty. Music always has a subtext that’s divorced from what’s on the screen. I think a composer is always trying to bring another layer of reality to the movie. But there’s also the constant of the movie and the imagery behind the truths. And it has to work like that, otherwise it just becomes like Teflon and splits your music off the screen.

Other than the theme, what did you decide to bring back from “Batman Forever”?

There’s not much. There’s the theme, there’s the trouble in Gotham [theme], there’s music which was underused [in the first film] which was what I call the ‘Gotham City Boogie’. And what we did was take the boogie out of it but kept the high strings because I thought it would be nice for that to be developed to the third power even – even crazier and wilder. But, I’d say bringing the choral element in is another departure. There’s a lot of chorus in this movie.

When you’re dealing with a film like this that’s so wildly visual, how colorful do you think you can get with your music before you feel, personally, that it’s sensory overload? Or is it go for broke and see how colorful everything can be?

In a way it can’t be as colorful because when the film is action-oriented and has a lot of futuristic gadgets and large automobiles and motorcycles and things like that, from strictly a film score approach one has to be a little bit more megalithic, solid, and basic with a lot of the materials, so that they can live in harmony or at least work with sound effects. If the orchestration and the approach to instrumentation are too colorful then it won’t be heard because sound effects are extremely vital to a film like this.

Is there an attempt to rectify the score with the effects, or are you both vying for attention?

Ah, that’s one battle that I’ll never win so I don’t even think about it. In a way I just decided that, when in an action scene, the music has to be really strong blocks of sound as opposed to a lot of musical pointillism.

I loved some of the coloristic combinations that you came up with in your first “Batman” score – the kind of theremin, soprano, and saxophone things, the harmonic choir, the really low double reeds. How do you come up with all these colorful combinations?

Well, I’ve always been in love with low double reeds.

The standard ones or things like hecklephones?

No, no, no. Hecklephone is in this score too! Actually, a little bit more precise, it is a bass oboe. It’s slightly different in the sense that one is curved and one is not. [Bass oboe is curved, hecklephone is straight.] There’s bass oboe, there’s contrabass clarinet. Contrabass clarinet has probably been in at least ten of my scores. There have been solos that are pretty audible in “Interview with the Vampire”. I’m using oboes in a rhaita style, which is Moroccan-style oboe playing where you actually put your whole mouth over the mouthpiece and overblow and it has a very raucous kind of North African sound.

Yeah, Corigliano used that in his Oboe Concerto, right?

Corigliano used that in his Oboe Concerto and it was very effective. I was a student of his at the time so I was exposed to that technique.

There’s a lot of lower brass writing in this. There aren’t any specialty instruments, but there are a lot of, I would say, tricks. Like for example, when I wanted a kind of pan-Arabic sound I had the cellos – the strings, basically – put ripped Styrofoam cups underneath the bridge and play. And it created this wonderful buzz.

How do you come up with some of these things that haven’t been tried before? Is it just combinations that you’re going to try and see what specifics result?

Well you know, even though the schedule is crazy there is a chance to change things on the stand, so I tend to be a little bit more expansive and experimental. We’re trying not to be more expensive to the studio. There’s a bass sax on this score!

Really?

Yeah. There’s a character called Bane and the music has to be like something out of – I don’t know, like Franz Waxman or something. It has to really be like something out of a Frankenstein movie. This creature is being created and I just needed more and more pop on the bottom reedy end. Along with chimbasso which I’m using instead of tuba for most of the movie.

Are there any other specific favorite new orchestral colors that you’ve come up with for this score?

Well I’m mixing standard Wagnerian orchestral techniques in with my own bit of standard stuff that I do, but also with a lot of big band jazz configurations. So in a lot of the action scenes they take on a big band jazzy kind of quality with a lot of trumpet shakes, things like that.

I love the way that in a lot of your scores – even in the last “Batman” score – when you approach some of the 20th century compositional techniques they don’t have to be equated, necessarily, with fear or panic as they are in so many other scores. There’s a scene in “Batman Forever” where you used some alternate clarinet fingerings just to represent a flipping coni. Are there certain kinds of on-screen actions that you feel can handle these more contemporary devices, or is it just a facet of your style?

There are a lot of alternate woodwind fingerings and horn modulations and bass modulations and the things that you might expect from the Polish avant-garde in the 1950s and ’60s that are just part of my vocabulary. [Alternate woodwind fingerings produce tones which are slightly out of tune and sometimes “fuzzy” sounding. Horn and bass modulations refer to the bending of the pitch slightly above and below a standard pitch. –DA] And they seem to work very well in these movies by creating these intangible worlds. Of course you have to be specific with – like you say, flipping a coni. Or, in the case of Poison Ivy, she kisses you and you’re poisoned and you die. So I use these woodwind alternate fingerings and horn modulations because you almost get the sense of the poison oozing into your system. It creates a very uneasy microtonal kind of a feeling, especially if you juxtapose it against a sort of sexy, jazzy alto saxophone. And when it starts going into these kinds of alternate fingerings and tunings you feel like, “Oh, my God, yeah, I can feel the poison going inside me.”

So when you’re spotting the film, obviously you’re not looking for spots where you can sneak these devices in…?

No, it’s more natural. I mean, I have been living with these sounds in my head for the last 20 years easily. So it’s not like, “Ah ha, here’s a spot for a 20th-century technique.” It’s just part of a palette that just floats around in my head all the time.

You talked a little bit about how you can develop themes more when you’re doing a sequel score. Does anything else change as far as your approach to doing a sequel compared to doing a first-time film?

When you’re doing a sequel, it’s kind of like you’ve already broken ground on some of the most important thematic materials. So in essence you’re not sort of auditioning the world or trying to create the world. Now that you have the world you can be a little bit more free in terms of how you manipulate it, because you’re a bit more familiar with the territory. And so is the director and the studio. It has that hint of familiarity so that everything isn’t constantly new for them.

I’m assuming that, like that last film, this one is going to kind of jump back and forth across the line between action and comedy. How do you deal with that juggling act with your music? What kinds of musical statements sum up this dual dramatic purpose to you?

Well, I don’t think of it as an action film as much as I think of it, like Joel Schumacher described it, as a comic book opera. I think of it more in a world with what one expects when you turn the pages of a comic book and you see things flying around and the whacked-out perspectives and colors. That’s the kind of genre this is, as opposed to seeing it as three separate things – as comedy, as drama, and as action. I just see it constantly, from moment to moment, as a comic book extravaganza.

Do you feel you have certain kinds of musical gestures that you make in your own compositional style that work better with a comic book opera?

Yes. Broad strokes. Something that’s sort of film noiry, for example, in the Poison Ivy character. You know, composing music that really would have fit absolutely beautifully into a film noir movie in 1954 or something. Just being really true to the style – the truer you are to the essence of the style without making fun of it or fucking it up too much it what seems to be the most successful way of approaching these scenes. Like serious, big orchestral music – if it’s serious and Schwarzenegger’s in it as Mr. Freeze, [that] seems to work more than if I poked around with the style too much where I’m not really taking it seriously. You have to take these characters seriously, even though you can’t take it seriously!

So, kind of playing it straight is key, huh?

Right. Try to be creative within playing things straight.

Speaking of the spotting sessions, I’m assuming that like the last film there will be an awful lot of score in this one. It was pretty fully scored in the last one, wasn’t it?

Yeah, there were over a hundred starts of music. There are more starts of music in this film than in the last. I looked for the spots where there’s no music, and there are like 58 seconds with no music.

Wow. How do you go through that huge amount with the spotting session? Is it just, “Well, I need music here and here and here!”?

Heroic, foreboding, romantic – those broad, broad, broad words come into play.

So it’s more emotional type of stuff than anything else?

In terms of the words in the spotting. Actually, to be fair to you, the most important things in the spotting are when the in’s and out’s of the specific type of music are, and where the next type of music takes over. So it’s just identifying the spots.

Obviously there’s the song album coming out, but can we expect a CD of your music as well this time?

Yeah, I think there’s going to be a CD, but it’ll probably typically be released about six weeks to two months after so they can grab as much as they can out of that rock album.

What do you think it is about the Goldenthal approach to scoring “Batman” that you consider different from all your predecessors? It’s been approach by so many different people now.

I don’t know. I think what’s in my personality in general is a very, very wide-embracing musical vocabulary that can reflect the wide-embracing world of Joel Schumacher’s vision. I’m happily familiar with many genres and really revel in working on a movie where you can express these genres without it sounding unusual. A whacked-out jazz sort of thing that I did with Mr. E in the last movie with the strange farfisa organ solo – it could be something that one would expect to hear in the concert hall or if could be something that one would expect to hear in a beer hall.

If there’s anything about my personality, it’s that within my own style I do embrace many, many different styles. I don’t tend to subdivide as much as other people. But, I have no criticism of the last composers who have worked [on “Batman”] because it’s there sacred relationship with their collaborators.