Elfman describes his ambitions as an artist, trying to achieve integrity through his writing despite accusations to the contrary. He talks about his musical influences and even tries to create a public persona resembling Herrmann's. He talks about the pervasive issues of poor sound mixes in movies, including Burton's.

Today is a special day for Danny Elfman – which has nothing to do with any film or film score. It’s the day a week he spends with his two daughters, who pretty much bounce off the walls as their daddy arms himself with coffee for yet another film music interview. “You’re here to talk about film music?” he says. “Well, film music sucks, that’s pretty much my opinion.” He is marginally amused to see a copy of FSM from some months back where every letter fell under a heading of something “sucking,” complete with a cartoon of Jerry Goldsmith reading FSM and thinking, “This magazine sucks.”

The Elfman “compound” is one of those Southern Californian homes built high into a cliff, with a spacious, vertical “yard” rather than a ranch-like horizontal one; it features all kinds of plant life even surrounding a little stream. The house is marvelously decorated with “Nightmare Before Christmas”-like skeleton-chairs and knick-knacks, including a shrunken head mounted in a glass case. It’s part normal house, part “Addams Family” and part “Pee-Wee’s Playhouse” – gymnast rings, for example, hang outside his studio, a separate, smaller building, presumably so he can get up and stretch on them at any stressed-out time. Elfman is even dressed like he could be a character in “The Nightmare Before Christmas”, with an “alternative” striped T-shirt, a face much younger than his 42 years, a fabulous frock of bright red hair – most fans probably don’t realize what red hair he has, since film music magazines are cheap and printed in black-and-white – and even some newly applied tattoos.

To begin to understand why Danny Elfman thinks film music sucks, one must understand his own peculiar entry into the field, meteoric rise to the top of it, and disenchanted withdrawal into a self-imposed two-film-per-year schedule. Danny Elfman has no formal musical training; as he puts it, he didn’t go to music school, he went to film music school – the local movie theater in Baldwin Hills, California (a suburb of Los Angeles) where he and his friends would go every week to take in the latest cinematic offerings. “I don’t know when I first saw ‘The Day the Earth Stood Still’ – it couldn’t have been when it first came out, because I hadn’t been born yet – but that had a major impact on me,” he says. “I loved Ray Harryhausen’s animation with Bernard Hermann’s scores, to the point where if it was Harryhausen without Herrmann, it just seemed incomplete. Obviously I loved fantasy and horror, the darker the better; in fact, when comedies or musicals came to the theaters, myself and my friends would boycott.” It was through this process of being a movie fan that Elfman came to notice the different styles composers had, the absence of which he laments in today’s movies. “By the time I was a teenager, I prided myself in recognizing the music of my favorite composers. After a while, I’d go, oh, this is Steiner, and of, this is Herrmann, or Tiomkin, or Waxman, there was something unmistakable about them.”

Elfman was a rock ’n’ roller with the popular band Oingo Boingo (they provided the song ‘Weird Science’ to the movie of that same name) in the late ’70s and early ’80s – it ended October 31 of this year in a farewell concert – and was hired to score Tim Burton’s first feature-length film, “Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure”, in 1985. His quirky, off-beat but dramatically astute style was a perfect match for Burton’s bizarre visuals; to this day, his earliest comedy music is a model for scoring the countless, much lesser films churned out by Hollywood, as film editors routinely turn to the “Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure”/”Back to School” CD for temp-tracks. Step by step, with the help of Burton’s popular films and the representation of Richard Kraft – then a record producer at Varèse Sarabande, later an agent at ICM and now head of his own Kraft-Benjamin Agency – Elfman continued to rise.

Then in 1989, he scored “Batman”, and was suddenly huge. The “Batman” score was orchestral and appropriately gothic, but with a unique, Elfman-esque flair. Love it or hate it, there was and is a frenetic, idiosyncratic quality to his writing which is fun to listen to and dramatically effective, and therefore alternately loathed and imitated by classically trained composers who probably loathe it all the more since they have to copy it all the time. If there were big projects before “Batman” – “Beetlejuice”, “Scrooged”, “Midnight Run” – even bigger ones came in the three years after it: “Darkman”, “Dick Tracy”, “Edward Scissorhands”, and “Nightbreed”. He even revitalized (briefly) the television theme with “The Simpsons” and “Tales from the Crypt”. He called it quits on the action genre after “Batman Returns” in 1992, and then poured his efforts into “The Nightmare Before Christmas”, released in late 1993. He provided songs, lyrics, score, and several singing voices, including the lead voice – a mammoth contribution which resulted in him being as much the auteur of the film as Tim Burton, since both were involved from the very beginning before there was even a director or script.

“Nightmare” was not a bomb, but it wasn’t a blockbuster; Burton and Elfman’s dark Halloween/Christmas imagery made for an interesting and original film, but not a family classic or a rebirth of the musical. Burton and Elfman ultimately had a falling out over the picture, which to this day neither is willing to discuss, and Elfman was absent from Burton’s 1995 “Ed Wood”. “Nightmare” and its aftermath was important to Elfman in that it determined a new direction for him, which was not the route of the eight-picture-a-year film composer. He did a new rock album, “Boingo”, and commenced work on scripts, with an eye to direct. All these things – film composing, writing, performing, hopefully directing – would interlock in a new, unique creative career which would continue to pay the rent, but allow for different modes of expression at different times. The new career plan has paid off right away in his film music; 1994’s “Black Beauty”, last spring’s “Dolores Clairborne” and this fall’s “Dead Presidents” and “To Die For” are a quantum leap above his earlier efforts in terms of orchestration and complexity, while still being functional and effective as film scores.

Which pretty much brings us up to date. And it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to guess the reasons why Elfman thinks film music sucks, since they are the same ones about which Film Score Monthly readers complain: Movies are a business; temporary music scores have reduced composers merely to copying the extended styles; composers have to plagiarize in order to continue to work; sound effects are too loud directors are too dumb; there’s not enough time to write; there are few if any original voices or ideas. That last criticism is refreshing in a time when film scores have become so identical, the conventions so entrenched, and the composers so expected to write the same score over and over again, that the only way to judge film music is in degrees of accuracy to the original “source.” For example, score Z is a pretty obvious knock-off of scores X and Y, but the composer had no choice, and it’s pretty competently done, so we like it.

Elfman’s criteria, on the other hand, is more in degrees of originality. For him, if score Z is a knock-off of scores X and Y, no matter how close or not-close it is, it’s still a knock-off, so who cares? Lost forever are the infinite number of different and potentially much better ways of approaching movie X. Elfman does not get work based on his ability to write knock-offs of different composers – he’s the first to admit he’s not trained in the way John Williams is, and thus there’s no point in him trying to be John Williams. Plus, he has written so many of the “scores X’s” of the world in the first place – things like “Pee-Wee”, “Beetlejuice”, “Batman”, and “Edward Scissorhands” which end up in every temp score, and anybody who disagrees should watch “Honey, I Shrunk the Kids” and “Casper” – that it’s infuriating to him to see other composers rip him off, deny it, and all the while deny that he even “wrote” those scores in the first place.

SOUNDING OFF

“I do understand the fact that it’s just a money-making thing,” says Elfman, taking a drag from his cigarette, “but that doesn’t matter, you should still give it your own voice. Composers are always prone to imitating themselves, which is part of that subjective thing called one’s style or voice. It tends to reappear. Composers tend to have inspiration from various classical scores and early film scores, as has been the way with classical scores for hundreds of years. However, to my knowledge, I never remember Max Steiner plagiarizing Franz Waxman plagiarizing Bernard Herrmann plagiarizing Nino Rota. They all had distinct voices that were their own, wherever their inspirations came from. Today, a number of very talented composers seem to be plagiarizing so freely that it can be impossible to find where their voice is in a particular work. Cue by cue, one can hear John Williams become Thomas Newman become Danny Elfman become Jerry Goldsmith, as if following a temp track which in fact is all too often the case. Film music today is all about ripping things off. It’s one thing to do it well or have it well-executed, but if you’re just copying something that’s already been done, that’s all your doing. If one is just providing any style that is asked for, then one is, for lack of a better word, a hack.

“It would be one thing if that’s what they consider themselves, and they’re honest about it, but usually that’s not the case,” he chuckles a little. “So many composers will do scores that are just copying everything from beginning to end, changing a few notes or twists on a melody here or there. Stealing in film music permeates the entire business. If someone does do something original and it works, it’s then ripped off immediately by everybody else; it’s like a magnet, boom, everything for the next five years is going to rip it off. There are too many composers today who successfully bang out music by the yard like so much wallpaper, without any sense of artistry.” (Contemporary composers Elfman admires, for those wondering if there were any, include Jerry Goldsmith, of course, as well as Graeme Revell, Rachel Portman, Tom Newman, John Williams, Elmer Bernstein, and “four or five others.”)

Elfman cites John William’s classic shark theme from “Jaws” as an example which, if ripped off today, would be justified probably like this: “They’d say, ‘Well, it’s just two notes, it’s just a thing, anybody could have done that, so I’m just kind of doing the same thing, I’m not really doing John Williams.’ Well, the fact is, he did it first. It doesn’t matter how simple it is or where it came from, be brought it to a genre. It doesn’t matter how simple it is or where it came from, he brought it to a genre. It doesn’t matter to me whether I can identify John Williams’s classical homage for several of the ‘Star Wars’ themes. The fact is, he brought it to the science fiction genre and made it fresh. On ‘Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure’, of course I was inspired by Nino Rota; Nino Rota’s influence is all over it, but I was the first to take it and apply it to a contemporary American comedy. And then after ‘Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure’ came out, I heard Nino Rota-inspired music in every contemporary comedy for the next five years! And still, well, ‘Elfman didn’t do that, that’s inspired by Nino Rota,’ but that’s not the point. The point is they didn’t think of doing it for an American comedy. The fact that Nino Rota and Bernard Herrmann are my inspirations and show themselves in scores like ‘Batman and ‘Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure’ I’ll freely admit.” Elfman cites “Psycho”, “Vertigo”, “The Day the Earth Stood Still”, “Jason and the Argonauts”, and “just about everything” by Herrmann as among his favorites; Rota’s work for “Fellini’s Casanova” is his single most favorite score, the music getting into the film to a point where it’s “almost a musical with everyone about to burst into song and sing along with the score.”

“I’m really concerned about the direction the whole thing is going right now,” he says. “I won’t take on too many films, let them overlap, do two at a time, have to turn to arrangers and just churn it out by the yard, or start a music composing franchise with ‘protégés’ like several unnamed big shots are doing right now. With salaries hovering near the half-million mark and with the ability to spend several weeks writing a theme or two and having a team of arrangers do the work, it’s easy to see where the temptation leads.” Elfman has limited himself to two films a year, in between other writing and rock and roll projects, an unbelievable artistic commitment which, if thought about in other terms, is something akin to “losing” millions of dollars a year in projects he’s turned down. He has refused to sell out in an era where there is every reason to do so.

“Every year, because I’m such a cynical bastard to begin with,” he reflects, “I wonder if I’m not making a decision I’ll regret for the rest of my life. 20 years from now, when I’m dead broke, I’ll probably regret many of the decisions I’m making now. I might look back and think that I could have done such-and-such a number of pictures from 1990 to 2000. But the moves are around forever. I’ve done a couple of cheesy comedies when I first started out; I was struggling to do anything, just to get back in front of an orchestra. I wasn’t able to pick and choose, but now I am, and I don’t want to have more of these types of pictures following me around.” He here refers to the “Hot to Trot” and “Summer School” type flicks in the mid to late ’80s he might have been better off not doing. However, even on 1986’s “Back to School”, starring Rodney Dangerfield, he takes pride and some shock in the fact that although the film wasn’t much, the style of his music has continued in similar films – “just something about that vibe.”

“Besides, I get more cantankerous every year,” he adds, “something I’ve been working on quite actively, as I’ve been trying to model myself in Bernard Herrmann’s quirky image. I mean, composers are all assholes, myself included. We’ll never have a guild or a union because you’ll never get us all in the same room as the same time. For some reason we all seem to behave like male cats in an alley in here with one female. It’s not a matter of composers being pleasant or approachable, it’s a matter of them being assholes, at least to other composers. Maybe it has to do with nobody ever giving me credit for doing anything.”

Still, when asked why he should care about this, why he and other film composers shouldn’t just take the money and run, Elfman’s response is immediate and absolute: “We’re supposed to be artists.”

SOUND EFFECTS SUCK

After “Batman”, Danny Elfman did a number of action films (“Darkman”, “Dick Tracy”, “Nightbreed”) but it wasn’t a dislike of the genre which forced him to call it quits after Batman Returns in 1992. “Personally I love doing those big action films. I had a great time writing the score to ‘Darkman’. It was a big, old-fashioned melodrama, and I love big, old melodramatic score.” Instead, it was the interminable sound effects of the genre that turned him off. “It was during the screening of ‘Batman Returns’ that I decided I want to write music that will do what it was meant to do for a film; I don’t want to write music that will complete with an opera of sound effects. Contemporary dubs to my ears are getting busier and more shrill every year. The dubbers actually think they’re doing a great job for the music is a crescendo or horn blast occasionally pops through the wall of sound.”

The situation on “Batman Returns” was his worst ever. Elfman wrote his music with dynamics in mind, only to find that everything was flattened out by the dubbing mixer. The film was so poorly- dubbed that Elfman believes his music actually hurt the picture; had he known how the sound effects would have been used, he would have simplified his writing. “In the end result, I believe that if 25% of the score and 25% of the sound effects had been dropped, the entire soundtrack would have been infinitely more effective than the busy mess it became.” Many composers will argue that a good relationship with a director will help get their score across in the final mix, but unfortunately most directors “don’t have good ears, even the brilliant ones. With Tim Burton, I had my best and worst dubs back to back. I’ve never had a better dub than on ‘Edward Scisshorhands’, and I’ve never had a worse dub than on ‘Batman Returns’. No director does this consciously, they just lack the audio skills to deal with such a complex science.”

As an example of good dubbing, as practiced in the past, Elfman mentions “Lawrence of Arabia”, where the first several minutes of a huge battle scene are played solely with sound effects, and at a specific cut, the music takes over completely. “The music raises the emotional level enormously, and you’re not aware that all the sound effects have stopped, your brain thinks that they’re continuing. That to me is perfect dubbing.” Another example Elfman gives, enthusiasm bubbling, is Hitchcock’s sparse use of sound effects. “Hitchcock was wonderful at giving a heightened reality to a scene by being very selective with the sound. We would rarely hear sound effects for action that we did not specifically see, and he would let the music fill in all the holes in our imaginations. It let us imagine these things are there all the time, but we’re not hearing everything all the time, and you don’t think anything is wrong.”

Today, however, “sound people tend to look at each individual moment. They look at five seconds, and if something’s missing for a fraction of a second, there tends to be a panic. They don’t look at the context over the entire soundtrack and the entire film. Hitchcock’s films, if dubbed today, might become a whole different animal as the soundtrack would get filled from top to bottom, leaving no room to breathe, and certainly no room for Bernard Herrmann’s marvelous scores. There is a point at which all of this starts to wear down on the audience’s ears.” Elfman compares the experience of dubbing a film to mixing an album – in each case, you tend to scrutinize moment to moment, looking at every single instant, and if there are major flaws your ear tends to grow accustomed to them just my repetition. Even if it’s wrong, it will start sounding right. However, a major difference is that when you mix an album, you can “A-B” it with another recording just by popping in a different CD and re-aligning your ears. “You might pop in another album for comparison and realize, ‘Oh my god, there’s no bass!’ But it’s only by listening to something else that you realize that you almost completely lost your bass, because your ears will compensate for it and make you think you’ve been hearing it all this time. That’s a luxury we have when we’re mixing, you can pop in something else at any time and re-adjust your ears to see if you’ve slipped, but you can’t do that on the dubbing stage of a film. You can’t just turn on another film and go, ‘Beep-beep, A-B, whoa! Why does that other movie sound twice as good as hours? Maybe we’re doing something wrong here.’”

Elfman isn’t critical of any particular sound designer, as much as the entire freight-train dubbing mentality. “They’re simply doing their jobs, which is to provide every possible sound. It’s the mixer’s job to select sounds and ask, ‘Do we need to hear everything that you see and don’t see all the time?’ What contemporary dubbing is doing is taking all our imagination away from us.”

Nevertheless, film remains a medium obsessed with creating an audio-visual “virtual reality,” a type of sensory overload, to the expense of the story and characters, even though those are what people are going to see. “An audience very seldom realizes when they’re hearing a terrible score, any more than they realize when they realize they’re watching terrible editing. If they could magically see a scene edited much better, they would notice the difference, and likewise, if they could suddenly, magically see the same scene with a very effective score, they would find themselves unconsciously more involved.”

HE WRITES HIS OWN MUSIC, ALREADY

Nothing has been as pervasive or damaging to Elfman’s reputation as the constant believe and insistence by others that he doesn’t write his own music. Never mind the similarity of style from score to score; the fact that he has continued to write large-scale scores without using Shirley Walker to conduct, who people at one point assumed really wrote Batman; that the scores his lead orchestrator, Steve Bartek, have done on his own have been completely different from Elfman’s music; and the sheer illogic to the assumption that Elfman could have a hidden army of ghost-writers somewhere without anyone naming names or coming forward. Yes, it is true he came up with the theme to “Batman” while in an airplane, then went into the john and hummed it into a tape recorder. Many composers and songwriters have been known to carry around tape recorders and hum out a melody when it comes to them; some turn over the tape to an orchestrator to flesh out, many write it themselves. Elfman took his tape of him humming the Batman theme, brought it home and wrote it out himself at a piano with pencil and paper.

“I use orchestrators, not arrangers. The difference may seem subtle, but it's not,” he explains. “The orchestrator's job is to take music which has been clearly written and balance it for the size orchestra that has been designated. Steve Bartek has been my primary orchestrator on almost every film I've done. He never changes a melody, he doesn't add counterpoint, he does not change or add harmonies. That's the composer's job. He will elect what instrumentation might best express what I'm trying to convey in terms of doubling melodies and dividing the parts of the string section so they can be used most effectively. I don't want to minimize this job, it's very important. It's time-consuming and I, like most composers, depend on our orchestrator to complete the final stage of the scoring. John Williams uses orchestrators and he certainly doesn't need to. Prokofiev used orchestrators, though he certainly didn't need to. I use orchestrators for the same reason.” To give specific examples, if Elfman wrote three parts for strings, Bartek will decide which individual players will play which note to best balance the orchestra. He might also write out more orchestral parts than are eventually used; for example, the oboe music might include lines from the flute part, so that even though the oboist is not expected to play, his music will include the flute lines in case it is deemed necessary for him or her to “double” (also play) it. It's simply easier to have it all written in advance than to have to rush and have the copyist scribble out new parts on the stage. “We may have the first pass of a cue over-orchestrated, and then have to tacit parts, but better that than under-orchestrated,” he explains.

The orchestrator is helpful before the recording, as well as during it. “I have a tendency to overwrite, as you're well aware, and Steve is very helpful in finding train-wrecks before we get to the scoring stage. When I'm moving very fast, he'll be able to help me, like 'tell me where I fucked up by laying it on too dense.' Sometimes Steve will call me up, he'll say, 'Your melody is down there in this very loud section, I think you've got to make a decision between what the trombones are playing or where the melody is.'“

In two rare cases, Elfman has delegated a cue of a score to an outside composer, just to finish on time, Jonathan Sheffer wrote the helicopter music in ”Darkman”, and Shirley Walker did one of the climactic action cues in ”Nightbreed”. These resulted from Elfman knowing he could write 63 minutes of a 70 minute score in the time allotted, for example and delegating the other 7, often for particularly noisy, sound-effects laden cues he didn't want to deal with, to the outside musician. “The few times that I've asked orchestrators to do an arrangement and take a melody I've written and turn it into an original piece of score, I've always given them composing credit,” he states. (For proof, see the end credits of the respective films.) “That same philosophy applied in many films today would leave very long and embarrassing end credits.”

Elfman's first film was the aforementioned ”Pee-Wee's Big Adventure”, and he briefly toiled with the idea of doing it the usual ‘rock and roll method’, i.e. playing themes and having an orchestrator take it from there. But he realized “to really get your voice sounding original, you need to do more than that. I started doing that for two weeks on ‘Pee-Wee’, and realized, this isn't going to work. I forced myself to start writing the stuff out.” He got by on ”Pee-Wee” by the fact that “it was a very simple score”; same for ”Back to School”. “I got up to ‘Beetlejuice’ and over the course of ten scores got to the point where I could handle more complicated music and I had to push myself to do ‘Batman’. Once I got to ‘Batman’ I had the confidence to hold much denser pieces in my head, because in order to write I have to mentally freeze the entire piece of music and write it down one part at a time. Same thing leading into ‘Dolores Claiborne’, I couldn't have done that at the time I did ‘Batman’, because at that point I couldn't really do dissonance, I had a hard time holding onto chords with odd voicings and movements, and moving things around in a non-rhythmic way. The key scores for me were ‘Pee-Wee’ to ‘Beetlejuice’ to ‘Batman’ to ‘Dolores’, those were the big jumps, for me at least; I’m not saying they were great leaps for music-kind.”

LOOK: SCORES!

“It's always amazed me how far and widespread the rumor that I hire other people to write my music has gone,” Elfman states. “It's most interesting to me that Steve Bartek, who has orchestrated 95% of my music, never seems to be the one given that credit, which usually gets bestowed on conductors and secondary orchestrators, for reasons which I can't fathom. I've only heard a thousand times that Shirley Walker 'really' wrote the score to ‘Batman’, that Bill Ross 'really' wrote the score to ‘Beetlejuice’, that Mark McKenzie 'really' wrote the score to ‘The Nightmare Before Christmas’ – the list goes on and on, and it's very boring.”

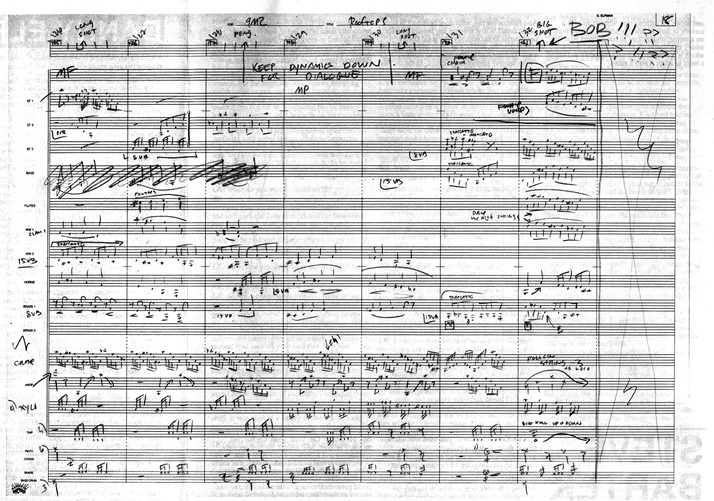

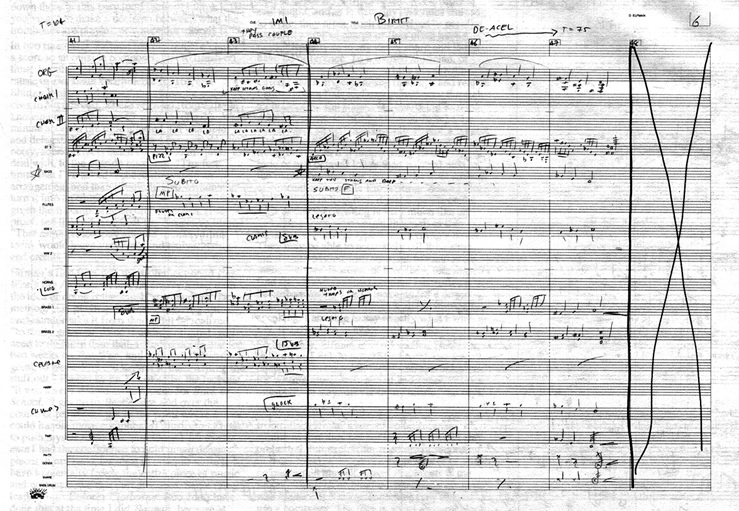

However, he does he write his own music, and now, what started out as a challenge from a member of this otherwise unnamed group – “I'll believe it when I see it” - is a reality. See above a page of Elfman’s sketch for ”Batman Returns” (9M2, “The Rooftop”), and on the next page over, ”Black Beauty” (1M1, “Birth”), each in his own hand. If people still believe this is a fabrication, then there's nothing anybody can do.

Elfman's initial response to a request to print his sketches was an emphatic “No way!” and one just has to look at his work to see why he might be defensive. “I'm embarrassed for good musicians to see my written music. My writing is self-taught, and as is with any illiterates learning to write, they often teach themselves in peculiar ways. My uses of sharps or flats often have a random quality as to my ear A-sharp and B-flat have no difference. To a trained musician, of course, they are different, in how they're read. Often I catch myself writing in sharps and realize I should be in flats and switch half-way through a phrase, creating some very confusing looking notation, particularly when changing keys. In that sense, I'm certainly an orchestrator's biggest nightmare. Also, I'm most comfortable writing in treble clef, even if it means using 15 or 31vb [one or two octaves lower than written] next to the phrase because this requires the least amount of concentration while I'm writing. When I feel alert, I write in bass clef, it just depends on the time of day. My writing is very much like an illiterate person who taught themselves the alphabet and how to type while writing a novel. They may be able to accurately tell their story, but it will be filled with misspellings and grammatical errors. Because of this, they, like myself find the viewing of their original manuscripts to be embarrassing. I can't make up for a dozen years of training that I never had, but musically speaking, I am able to say exactly what I wish to say, though often in awkward ways.”

So basically, Elfman is a bad speller. However unlike a self-taught novelist who can use a spell-checker on a computer, there's no spell-checker for writing music with pencil and paper. “Those misspellings stay forever in my music,” he says.

Ironically, Elfman's latest two projects are similar in that they are not fully written out and orchestral, but exploit the medium of recording in order to layer different samples, most of which he performed himself. “Dead Presidents” is the second film by The Hughes Brothers; their first was “Menace II Society”, for which they did not use a composer. The film is about a young black man and his experiences from 1968 to 1975 through inner city life, Vietnam and then a bank heist towards the end of the picture. (The title refers to money, which has Washington, Lincoln Jackson, and other “dead presidents” on it.) Most of the soundtrack is made up of classic ’60s and ’70s funk; Elfman's score plays a major role in the main title, Vietnam scenes and climactic heist. Co-director Allen Hughes was very generous of Elfman's contribution in a recent Hollywood Reporter, noting, “On ‘Presidents’, we worked with a composer for the first time; Danny Elfman. He does some things he's never done before, a really interesting mix of percussion, industrial sound and orchestra. We worked closely with him but mainly just told him what we didn't like. He taught us what music can do for a scene in terms of the score; he made some scenes ten times more dramatic. We hadn't experienced that on ‘Menace II Society’. He showed us how powerful it can be.”

Of the film, Elfman offers, “It's a percussion based score, sampled percussion, of which I pre-laid every cue, so that half of the score is my own performance. Then we laid orchestra on top of it. It's actually a way of working that I don't like to do as a rule because it's so much more labor-intensive. It means I have to pre-record every single cue before we go to orchestra. But it's what that particular score required, they [The Hughes Brothers] wanted a percussion-based score.” EIfman's main title is his only cut on the ”Dead Presidents” album, but the composer hopes to include several more Dead Presidents cues on a second Music for a Darkened Theater compilation from MCA, planned for some time in the next year or so.

EIfman's other score in a recent movie is ”To Die For”, Gus Van Sant's black comedy starring Nicole Kidman as a fame-obsessed, would-be television personality. “‘To Die For’ has a lot of synthesizers in it, but is more orchestral than ‘Dead Presidents’. It's kind of hard to explain.” Both films feature this sampling and orchestra technique, particularly in their main titles, so as to achieve instrumental combinations one could never get in “real life” - i.e. a Church organ, then an orchestra, then thrashing electric guitars, all over a percussion track and odd sounds, play in the same piece. The music draws in the audience, pulling off the crucial opening minutes of a movie when it is imperative that people shut up and get absorbed.

Elfman was absent, however, from a certain big-budget movie earlier this year, “Batman Forever”. The reason is very simple: "they didn't ask me," he says. He wasn't too disappointed initially, having heard that the filmmakers wanted to go in a different direction; however, then he saw the film, and was surprised to find much of Elliot Goldenthal's score similar to his own Bat-music in sound and style. Elfman also knows what the first Oscar-nominated score of the year will be, because he walked out of the movie due to the music, and “whenever that happens, I know it will be Oscar nominated." (What that is, however, he isn't telling.)

And thus we get the impression of the Good Danny and the Evil Danny. There is the Danny who is an all-nighter workaholic to do the best he can on his own scores, and the Danny who thinks it all sucks the Danny who speaks of the things he loves and admires, and the Danny who also speaks out against the industry. There's the Danny who is proud of what he has been able to accomplish, and the Danny who rolls his eyes in disbelief (and also pity that people would waste their time in such a manner), when told of a "rec.music.artists.danny-elfman" newsgroup recently started on the Internet. But that's all pretentious – this isn't a transporter accident, it's just one guy, a film music fan, unquestionably talented, who has paid his dues in hard work.

"There's a big bitter contingent of people out there who feel like their place is being robbed by people like me," states Elfman the composer, forced back into self-reflexive mode and still paying for the career-defining error of admitting he has no formal education. "The most annoying thing about composers is their inability to accept the possibility that one could be self-taught. That doesn't exist in any other field in film. A director doesn't need to go to film school and no one will question him. But a composer cannot be a composer doing their own music without going through formal musical training. If that's what they think, fine, I don't give a fuck. The fact that there are a lot of composers that on their own would be better orchestrators than me, that's great. I think a good proportion of the composers working out there are really just orchestrators, and haven't a fucking clue what to do with a melody or how to use it or how to do variations on a theme; and/or they're songwriters who do what I'm accused of doing, although I don't, which is just coming up with melodies and hiring a team to adapt it into a score."

And Elfman the fan, what does he think? Is film music dead? Will it ever get any better? Despite pretensions to the contrary, the good Danny comes through, and he's as eager and hopeful for a new Golden Age in film music as anyone. "Who knows? Everything is cyclic. In the decade before ‘Star Wars’ the big orchestral score was practically dead in the water, and everything turned around overnight," he states, matter-of-factly. "Anything can happen."