Analysis of how Broughton's music accords with the film. Adams cites the distinct English flavor to communicate the time and place of the film, and the themes' references to British folk tunes. All of the motifs are discussed briefly. Broughton makes an interesting comment about how he does not use a method to score a feature film, and merely starts at the beginning and ends at the end.

Classical “art” music always seems to get the benefit of the doubt. Everything written into it gets constant examination and re-examination simply because of the medium in which it exists. Sadly, film music is rarely this fortunate because, for one, the deluge of film music that comes out each year makes it difficult to analyze thoroughly those scores which merit discussion, as they must first be separated from the rest of the pack; and most importantly, two: film music is rarely considered art by those in the position to further it along. If film music is ever to establish a sort of literature about it, then it must be seriously considered. Good film music almost always embodies the same sort of intricacies that if included in a classical piece would make critics drool and rave about how much consideration the composer must have put into his craft. These scores deserve a proper examination, and one such work is Bruce Broughton’s “Young Sherlock Holmes”.

In 1985, Steven Spielberg and Barry Levinson brought Chris Columbus’s story of Sherlock Holmes’s first adventure to life with “Young Sherlock Holmes”. The film was a rather dark tale of young Holmes and Watson uncovering an Egyptian cult in appropriately fog-shrouded Victorian London; this led to some ‘80s special effects sequences and a climax in the Egyptians’ lair seemingly out of “Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom”. The picture did little business, but featured a well-written score by Broughton, fresh off his success with Silverado. Over the years, as more and more people have seen the film by way of cable and video rentals, the score has become one of Broughton’s most popular and sought after. And for good reason; it is a wonderfully complex and eclectic work that encompasses both nostalgically tonal and surprisingly contemporary music. It is successful both functionally and artistically. What follows is a (hopefully) complete analysis of the score as a whole.

Creating the Setting

One of the most important functions of the “Young Sherlock Holmes” score is to set the time and place of the film. Broughton himself recollects “… the movie itself was quickly paced. The scenes all sort of telescope into each other. One of the things that Barry [Levinson] was trying to do was make it move really fast.” When a film movies at such a rate, it can’t afford excessive time in setting up its surroundings. This is where Broughton’s music comes in, for it is decidedly British in nature. It immediately puts us in the proper mindset for a Sherlock Holmes adventure from the main titles on, which frees the story to move right along without excessive set-up. This British context is created in two ways: first and most noticeably it is accomplished harmonically.

The tonal music in this score uses harmonic progressions which would not be at all out of place in England of the past. Broughton refers to this as a “sort of English Elgar style.” This is most prevalent in the main character themes (see below). To further define the music’s geography he uses some modal harmonies native in folk pieces of the region. We hear this harmonic style prominently when Watson and Holmes walk about town investigating while surrounded by street vendors. In “Fanfare”, Royal S. Brown referred to this as “the kind of modal bounciness that seems to be the ‘in’ sound for costume dramas,” and while I hesitate fully to agree, it does remind one of the types of songs we may, perhaps stereotypically, expect to hear these people singing.

Secondly, the British atmosphere is achieved through instrumental color. The orchestrations for both the tonal and atonal music are full of soloistic passages for woodwinds and brass (most notably flute, oboe, and trumpet) and string tuttis, all of which readily recall both British art and folk music. One may argue whether or not this reads too much into the score, but the fact is, as Broughton does all his own orchestrations and therefore has total control over the final result, it was probably intentional. Mark McKenzie and Don Nemitz are both listed as orchestrators, but as Broughton says, “Without saying anything against Mark or Don who are both really good at what they do, all my orchestrations – no matter whose name is on it – are always my orchestrations.” [See CinemaScore #15 for an article on how Broughton works with McKenzie; CS is a now defunct film music publication from the ’80s which puts FSM to shame, except it only came out every couple of years. Issue #15 can be ordered from the publisher, Randall Larson, PO Box 23609, San Jose CA 95153-3069, $8.95 U.S., $17 Europe, $20 rest of the world. –LK]

As for the contemporary (atonal) music, since it cannot create this setting harmonically (as far as the old England goes, that is) it accomplishes the task by utilizing the same kind of orchestral colors as the tonal music. However, this was not Broughton’s conscious choice. He concedes that it occurred, but “that wasn’t intentional. It may just sort have glommed on to me because it was a very British picture and, you know, when you’re doing these things and, you know, when you’re doing these things, or at least when I do them, the style just sort of creeps onto whatever you do. [On] ‘The Boy Who Could Fly’, which followed that, I went, intentionally, for a much airier kind of orchestration. I had a lot of divided strings; I kept the voicings high. The tune is much, well, not much longer, but it’s a much lighter kind of tune. It just sort of floats, you know? Whereas [on] ‘Sherlock Holmes”’ that theme was very straightforward. It’s very pointed towards an end. It’s much more aggressive. So all these scores will have material that really comes from the film. It’s just a response to the film.” So, even though Broughton may not have planned these colors in the contemporary music he does not deny their relationship to the film.

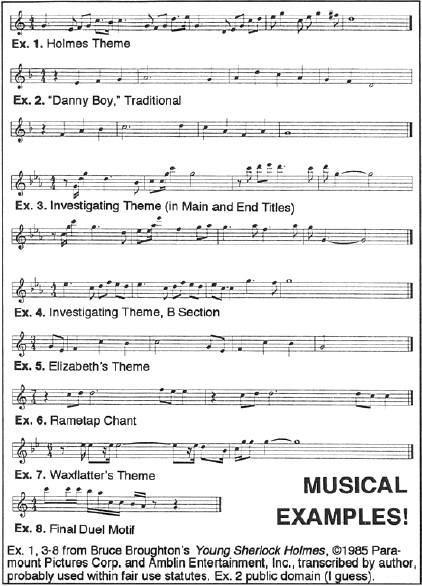

It is also interesting to note that the phrase shapes and contours throughout the film are consistent with the region. (Again, this includes the atonal music.) The melodic phrases are relatively short and often an entire theme will be a set of variations on a single movie. See, for example, the Holmes theme (ex. 1). The main motive is repeated almost verbatim in the first two phrases and is slightly more varied in the third. Think of the popular British folk tune “Danny Boy” (ex. 2). Here we also see two phrases begun with a similar musical hook; in both cases the pitch material is slightly altered the second time, but the source remains the same. Other than folk music, the music of Holst, and again, Elgar, was probably influential as that is (generally speaking) the style of music we have come to associate with middle to upper class English society.

Broughton also brings a great deal of thematic material to his score. What immediately leaps out about the seven or so character themes he uses is the variation with which they are presented. With many scores we are given an original version of a theme, be it as a main title, its first presentation, or as a concert track on the album, but with “Young Sherlock Holmes” each variation seems to circle around the others without any one emerging as the unaltered form. Even the opening title music constantly shifts its themes around so that no interpretation prevails. This also serves the score well because the film movies at such a pace that themes are repeated often. With so many versions of each theme, none becomes tiresome. For example, Holmes’s theme (ex. 1) appears in almost every scene Holmes is in, which is the vast majority of the film. The theme, however, manages never to become overused because of its endless variations. It is generally presented as a solo for trumpet, but often finds itself scored for woodwinds. It is altered in terms of harmony, rhythm, and style as well. It is a “very boyish and very enthusiastic” theme, “almost like an English marching song,” in the composer’s words.

The secondary theme of the film is seen in ex. 3, as used in the main and end titles. This is what Broughton refers to as the “investigating theme.” He says, “That was used whenever Holmes was looking around, whenever he’s on the case.” Again, this theme is generally presented as a solo, usually for piccolo or oboe. When used as Holmes’s leitmotif, it is used interchangeably with ex. 1, but also serves as an underscore to Watson’s actions. These two intertwining main themes can be seen as a musical representation of Holmes and Watson’s partnership. In addition the B section of this theme (ex. 4, also introduced in the main title) sees a bit of action throughout the score, also in constant variations.

The next theme, Elizabeth’s motif (ex. 5) provides one of the most interesting stories associated with the score. This theme’s beginning is similar to Holmes’s in its pitch content; however, it was not a case of sloppy workmanship or carelessness. Rather, it is a purposeful relationship with a meaning behind it. Broughton says that one theme is “a variation of the other and, in a sense, she really was a variation of him. She was like his feminine side. In a longer version of the movie before it was cut down, a lot of things in his character, his personality, were explained by the characters in the film. He gets his cap from the girl’s uncle, he gets his coat from the teacher, and then he gets his pipe from Watson. But, he gets his deductive skills from his girlfriend. That’s not clear in the picture, but that was definitely intended in the script – that she would do all this deductive reasoning and he would learn from it. And they would do things back and forth with each other – little tests so that he would have these abilities.” Levinson noted that these themes were similar when Broughton played them for him. “[Levinson said] ‘Well, it’s basically the same tune, isn’t it?’ and I said, ‘Yeah, but they’re so thickly wound with each other that it seems to be appropriate.’ [And Levinson said] ‘Ehhh, okay.’”

Ex. 6 is the “Carmina Burana”, Car Orff-esque Rametap chant. When Broughton received the film the chanting cult members had already been filmed and it was up to him to work the chorus and orchestra around the pre-existing material. So, he took the on-screen chant (“El maltemal, tey han de brahn mobbit,” which may or may not be an actual Egyptian text – Barry Levinson couldn’t remember at the time), composed the theme uses the lyrics

Rametap / Etare Homentop / Etare Syristep / Etare Homentep / Etare rame Ramelep

and re-recorded the entire piece. (The lyrics to the choral section “are nonsense syllables formed [by Broughton] from the classical pseudo-Egyptian names.”) The barbaric effect of the theme belies its complexity; it gets an unsettling rhythmic feel from its 7/4 meter and if often heard away from its choral presentation as a leitmotif in the score proper. Its appearances are usually as oboe sols scored in the high register of the instrument so as to capture the nasal, bell-like tones we often associate with middle-eastern music.

Ex. 7 is Waxflatter’s theme. Waxflatter is Elizabeth’s uncle, an eccentric old inventor, and his theme is appropriately quirky. This theme, however, serves as a great example of Broughton’s versatility. He doesn’t let its outright goofy quality inhibit its usage in the score. Waxflatter’s theme is played during his death as a somber reminder of the man he was; it is presented here soloistically against a chordal background. Later in the film, Elizabeth, suffering from a hallucination, sees the dead Waxflatter try to bury her alive. Here his theme is presented rhythmically unaltered, but played in tone cluster.

Ex. 8 is a short motif on which the “Final Duel” music is based. This scene, the climax of the film, was scored in what Broughton describes as “one long day”. The entire cue is based on this theme and its variations, with Holmes’s themes (ex. 1 and 3) interjected at appropriate spots. The “Final Duel” theme is a quickly moving motive usually scored for violins. It weaves its way through the fabric of the cue, used both at the forefront of the music’s texture and as an accompanying figure to more prominent brass lines. Its minor mode and accentuated downbeats give it a kind of tromping, swashbuckling sound which well suits the fatal fencing match.

A few minor themes appear briefly in the film as well. There is a character theme on clarinet for the mysterious cloaked figure, and a motif from the first hallucination in the opening of the film reappears during the temple fire near the end. In the case of the hallucination/fire motif, however, no thematic connection is implied. The temple fire scene was the only one which Barry Levinson asked Broughton to re-score so that the scene played bigger and, as Broughton says, “it was come sopra [an Italian musical term meaning ‘as above’]. I was just struggling for material. So, I knew that there was a cue that I had done before that I knew would fit the situation. So, it’s just a matter of using the same music.”

Each theme is put through many wonderful variations, from mode to texture to phrase length and so on, always with great sensitivity to the particular scene’s needs. This is one of the great strengths of the score. Broughton says of his tunes, “Wherever these themes come from, who knows?... In all these themes I try and figure out what the essential theme or character feels like – if I can grab a basic essence to it. Like whether it’s adventure, whether it’s exhilarating, whether it’s sad, depressed, whether it’s romantic, whether it’s sustained, whether it’s quickly moving. Whatever it is I get the character of the music from the actor’s character, or from the situation and then I try and hold that feeling and bounce notes. Either a tune comes up, or I just bounce notes around trying to keep that feeling… sometimes I get started on things knowing that I can’t come up with a better theme, and I have to really work [laughs] to be able to make sure it does all the things that it’s supposed to do. There are certain ways I can harmonize it, certain instruments I can put it with, certain instruments that I avoid. Sometimes the material works easily and sometimes you really have to work it… the music is always a response to the movie.”

General Comments

The score from this film, along with the score to “Silverado”, are two of Broughton’s most popular works. They are his most requested at performances and he has traveled to such far-off places as Belgium to conduct them. However, he didn’t feel nearly so confident when he was composing “Sherlock”. “I didn’t have any fun with it at all writing it. I was depressed the whole time. And I thought for sure I had a big pile of ca-ca when I finished, I was so tired, it was four and a half weeks, I guess, to do the whole thing and it was a killer job. And I got on the plane pretty sure that this was the end of the career. I really was not expecting anything at all. And we played the first cue and I turned to the music editor and said, ‘I guess it won’t be so bad! [laughs].” His attitude quickly changed as the recording sessions went on. “… I was really happy to do it. I mean it was really enjoyable. I had the greatest time recording it, and the guys I worked with were terrific. Barry and Mark Johnson and Spielberg loved the score, he thought it was just terrific. And it was just a real big kick in the pants.”

Throughout the movie the music perfectly catches the mood of each scene. When Holmes solves the “crime” as perpetrated by his classmates, we hear a jaunty English march; when Watson hallucinates that he is being attacked by French pastries Broughton shows his “Tiny Toons” self with bubbling bassoons and whole tone scales; in the cemetery scenes we hear a stark, atonal violin solo and passages where the basses and cellos improvise on given notes – influenced by Broughton’s study of Penderecki’s score; and when Waxflatter launches his flying machine for the first time we hear an exhilarating brass flourish. So, not only do the compositional styles differ as far as tonal versus atonal, but the different instrumental combinations available in the “average” sized orchestra (the Sinfonia of London) are used to their fullest advantage. The combinations of different sounds are well-balanced; we get just enough of each style to keep our attention in a film that is heavily scored throughout.

This balance was not just a coincidence. Broughton says, “I remember that it was a very complex and very well-structure score. Having said that: I don’t structure things like Alex North, [who] used to put three-by-five cards all over the place and mark the scenes out. I don’t do that. I really just go from the beginning of the movie and work to the end not knowing what I’m going to do next.”

The score also catches the action of the film without blatant Mickey Mousing and even the motion-catching passages are so weaved into the fabric of each cue that they work almost subliminally. Take, for example, the ‘Final Duel’. When listened to away from the film, only at the end of the battling music can one tell exactly what’s happening on screen (the throbbing bass line and tam-tam illustrate that the duel has ended in a death.) However, when heard with the film it is obvious in each phrase which piece of music highlights which motion, but the cue is written so that the passages don’t annoying stick out amongst periods of inactivity. All this from a cue written in a day!

As noted in the beginning of this analysis, “Young Sherlock Holmes” did little business at the box office. This has caused the score to be wrongfully snubbed. Royal S. Brown’s Fanfare review was all of seven lines long (listed under “Briefly Noted”) with such usual Brown inaccuracies as “less than subtle allusions to Stravinsky… and Profokiev.” Broughton has listed this as one of his own favorite scores and says, “You know, you work on something and say, ‘Gee, I really like this movie; I hope it does well,’ and then nobody goes to see it and then it’s ‘What a drag.’ And the bottom line is, your scores only become well-known if people see the movie. You can do the greatest score in the world to a movie nobody sees, and your score just sits there along with the film.” Only recently, through video and cable, has the score received attention.

Broughton says that he’d like to get a CD out some time, since the album was released by MCA only on LP and cassette, but “don’t hold your breath for it!” This is really too bad. It’s a prime example of a great score that would receive much more attention if more people were exposed to it.